The Christakis et al. (2004) study appeared in the medical journal Pediatrics, yet it deals with an educational question that parents and early childhood teachers face every day. The study took a scientific, research-based approach to a complex, emotional question: Does too much TV harm very young children?

Have you thought about TV's effects on your own learning or that of children you have contact with? No one wants to feel that children are threatened by television, yet TV is widely used as an “electronic babysitter.” In this chapter, you will learn how the Christakis et al. (2004) study and other, more recent investigations are helping to answer important questions about early childhood learning.

Learning about the Educational World

Just one research question about learning raises so many more questions about education. Take a few minutes to read each of the following questions and jot down your answers. Don't worry about your responses: This is not a test; there are no “wrong” answers.

- Do you think you watched too much television as a child?

- How has television watching affected your learning?

- How many hours of television does the average American child watch every day?

- Does the content of what young children watch make a difference? Is educational programming such as Sesame Street better for a 3-year-old than Saturday cartoons?

- How much does quality of early child care in general affect learning?

- Most television viewing takes place outside school, but its effects show up in the classroom. How do you think other forces outside school affect how children will perform in school?

We'll bet you didn't have too much trouble answering the first two questions, about your own experiences, but what about the others? These four questions concern “the educational world”—the educational experiences and orientations of people in addition to ourselves. Usually, when we answer such questions, we combine information from many different sources. We may also recognize that our answers to the last four questions will be shaped by our answers to the first two—that is, what we think about the educational world will be shaped by our own experiences and by the ways we have learned about the experiences of others. Of course, this means that different people will often come up with different answers to the same questions. Studying research methods will help you learn what criteria to apply when evaluating these different answers and what methods to use when seeking to develop your own answers.

Take a bit of time in class and share your answers to the six questions. Why do some of your answers differ from those of your classmates? Now, let's compare your answers to Questions 3 through 6 to the findings of researchers using educational research methods.

Question 3: Preschool children in general watch anywhere from 0 to 30 hours of television a week, but the average is more than 4 hours per day. Four-year-olds average 50 to 70 minutes of viewing daily, most of which is cartoons (Huston, Wright, Rice, Kerkman, & St. Peters, 1990).

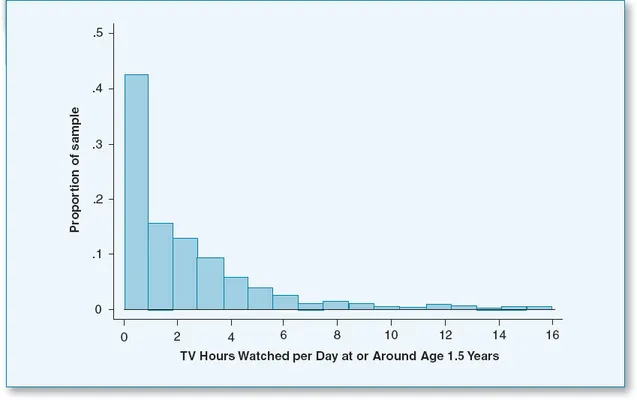

Exhibit 1.1 shows the amount of television watched by 18-month-olds in the Christakis et al. (2004) study mentioned earlier. Notice that the highest bar is at the zero level—no TV watching—and that more than half of the children studied watched 0 to 2 hours per day of television.

Question 4: Television viewing at an early age affects learning in school at a later age, but the connection is not a simple one. Important considerations include the type of programs viewed (commercial or educational), whether parents talk with children about what they're seeing, and how well children understand the difference between cartoon-type fantasies and real life (Peters & Blumberg, 2002).

Question 5: Conditions of child care, particularly the amount and quality of adult attention, can make a large difference in how television viewing affects later learning. Researchers at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (2002) studied the effects of early child care on more than 1,000 children. The study found that “children's development was predicted by early child-care experience” (p. 133). Educational development was connected to quantity, quality, and type of child care just prior to the child going to school. Higher quality care was associated with better language skills for 4½-year-olds, and after a certain point, the more hours children spent in care, the more behavior problems they showed.

Exhibit 1.1 Hours of Television Viewing for 18-Month-Old Children

Source: Christakis et al. (2004, p. 711).

Question 6: Many factors outside school affect learning in school. Physical and cognitive disabilities, for example, affect in-school learning for many children. Later in this chapter, you will learn of research on a legally blind preschool child in a classroom with 13 physically normal students. You will also learn of research that looks at cognitive effects on children when mothers work during the first year of the child's life. Economic and social factors play a large role in educational success or failure, and the federal government has created “compensatory” programs to level the educational playing field. One such program, Early Head Start, seems to be succeeding, and you will also learn of this research.

How do these answers compare with the opinions you recorded earlier? Do you think your personal experiences have led you to different answers than others might have given? Do you see how different people can come to such different conclusions about educational issues?

We cannot avoid asking questions about our complex educational world or trying to make sense of our position in it. In fact, the more that you begin to “think like an educational researcher,” the more such questions will come to mind. But as you've just seen, our own prior experiences and orientations, particularly our own experiences as learners and teachers, can have a major influence on what we perceive and how we interpret these perceptions. As a result, one person may see television as a way to extend learning to millions of children, another person may think television for preschoolers should be completely banned, and others may think the entire issue is overblown. In this chapter, you will begin to look at research results in an analytic way, asking what questions have been researched, what the results of these studies are and what they mean, and how much confidence we can place in them.

Errors to Avoid

Educational research relies on analytic thinking, and one important element of analytic thinking is avoiding errors in logic. As readers and consumers of educational research, we have a right to expect rigorous thinking in research articles. Errors in thinking can occur in the way a research question is constructed, the methods used to carry it out, or the conclusions the researcher draws. Becoming aware of some of the most common errors in thinking will give you a head start on becoming a smart reader of educational research.

Four common errors in reasoning occur in the nonscientific, unreflective talk and writing about education that we encounter daily. Our favorite examples of these “everyday errors in reasoning” come from a letter to Ann Landers. The letter was written by someone who had just moved with her two cats from the city to a house in the country. In the city, she had not let her cats outside and felt guilty about confining them. When they arrived in the country, she threw her back door open. Her two cats cautiously went to the door and looked outside for a while, then returned to the living room and lay down. Her conclusion was that people shouldn't feel guilty about keeping their cats indoors—even when they have the chance, cats don't really wa...