eBook - ePub

Exposing the Right and Fighting for Democracy

Celebrating Chip Berlet as Journalist and Scholar

Pam Chamberlain, Matthew N. Lyons, Abby Scher, Spencer Sunshine, Pam Chamberlain, Matthew N. Lyons, Abby Scher, Spencer Sunshine

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Exposing the Right and Fighting for Democracy

Celebrating Chip Berlet as Journalist and Scholar

Pam Chamberlain, Matthew N. Lyons, Abby Scher, Spencer Sunshine, Pam Chamberlain, Matthew N. Lyons, Abby Scher, Spencer Sunshine

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Analyses seminal figure Chip Berlet.

Features contributions by esteemed list of scholars and activists.

Focuses on many key contemporary issues such as racism, conspiracy theory and white supremacy.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Exposing the Right and Fighting for Democracy est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Exposing the Right and Fighting for Democracy par Pam Chamberlain, Matthew N. Lyons, Abby Scher, Spencer Sunshine, Pam Chamberlain, Matthew N. Lyons, Abby Scher, Spencer Sunshine en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Politics & International Relations et Fascism & Totalitarianism. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Part I

The early years

1 Chip in the 1960s

Sue Kaiser

DOI: 10.4324/9781003137276-1

Chip and I first met in a suburban New Jersey church youth group around 1965. He was formidably intelligent, irreverently observant of what was going on around us, and lots of fun. Together, Chip and I and our friend Curt Koehler developed a pretty strong feeling that lots of things in the world needed to be fixed, and that we should participate in the work, even though the nature of how we would do that was still evolving. There was lots of talking, sharing points of view, and listening to each other try on opinions and theories. And in the process of growing up together, we had wonderful projects and escapades: putting on plays, hosting a coffee house, showing avant-garde films, camping on Bear Mountain, going to jazz clubs in New York City, to Queens for a Simon and Garfunkel concert, going to each other’s high school proms. Chip always had a way of making events special—bringing a candle, packing a picnic, playing the right music, making slide shows of his friends set to James Taylor songs. I see this sense of ritual and ceremony continuing to show up in his work and life.

Our local Presbyterian congregation and the minister, Reverend Bob Reed, were intentional about providing learning opportunities for young people. We were offered experiences outside the boundaries of a traditional, doctrinaire church, and were enthusiastic participants because things were always interesting. And everything had an underpinning of inquiry—why are things this way and what do we think about it? How do people and institutions get held accountable? How does change happen? What is fair?

We had group exchanges with kids from a rural community in Vermont and an inner-city congregation in Hoboken. We visited Jewish congregations for Seder services. There was a project with a Greek Orthodox youth group several towns away to focus on how some Bible stories might be made more relevant to modern sensibilities. We were introduced to the Northeastern Ecumenical Conference youth camp in New Hampshire (Winni). There were times when we were “bussed in” to inner-city neighborhoods for service projects. Chip was already a competent photographer and gallantly documented one of my literacy education efforts.

We got sent as youth delegates to conferences, including the U.S. Conference on Church and Society in Detroit in November 1967 (Figure 1.1). The Conference took place against the backdrop of the anti-war movement, the summer 1967 race riots across the United States, the movement for justice for California farmworkers, the Civil Rights movement, and a fledgling women’s movement, to name a few. There were heady conversations about how churches and faith organizations could get beyond social norms and be accountable to core values in addressing inequalities, systemic racism, and violence. There was lots of moral indignation and discomfort going around.

Source: Photo by Chip Berlet, reprinted with permission.

Not content to do the usual conference thing and just sit in meetings, Chip sought out the extracurricular options and signed on with the “love feast” in Grand Circus Park. And, along with some well-known theologians of the day, we found the after-dark, dope-smoking circle. Heady times! Even then Chip had an uncanny way of finding the leading edge of issues and experiences.

Chip’s enthusiasm for Maggie and Terre Roche’s music led to “The Purple Kumquat” coffee house, which was probably pitched to some church committee or other as an outreach project. Chip’s poetry skill was evident even then and stands as a signal of his ongoing penchant for verse.

The Purple Kumquat

Aye, the Kumquat, oblong and orange. What became this fruit of the rutaceous tree to be purple?

’Twas the odd one of the fortunella genus envious of the well known fame of the bluethy plum?

Nay, for the answer is not that you may find by examining the syndromes of this juicy, vitamin C.

It tripped out on LSD and decided it was a water lily, held its breath, swam and purpleized.1

These experiences in and of themselves were not earth-shattering. But there is no substitute for stepping outside your comfort zone and early family/school/community experience for growing flexible hearts and welcoming minds. The idealism and limitations of all these “cross-cultural” exchanges were somewhat evident even in real time and probably helped instill in Chip and me an appreciation for the long timelines, personal relationship building, and systemic overhauls that are required for meaningful social change.

Note

- Copyright Chip Berlet. Reprinted with permission.

2 My friend Chip

Terre Roche

DOI: 10.4324/9781003137276-2

I met Chip Berlet back in the late 1960s in Park Ridge, New Jersey. Chip had started a coffeehouse in a church with his friend Curt Koehler. Coffeehouses with folksingers were all the rage back then. My sister Maggie and I were a folk singing duo attending Park Ridge High School. We played at Chip and Curt’s coffeehouse, which, if my memory serves me well, was named “The Purple Kumquat.” Maggie and I went on to have a career in music as the trio The Roches along with our younger sister Suzzy. Chip went on to dedicate himself to fighting the good fight against racism and oppressive right-wing organizations of all kinds, wherever they reared their ugly heads.

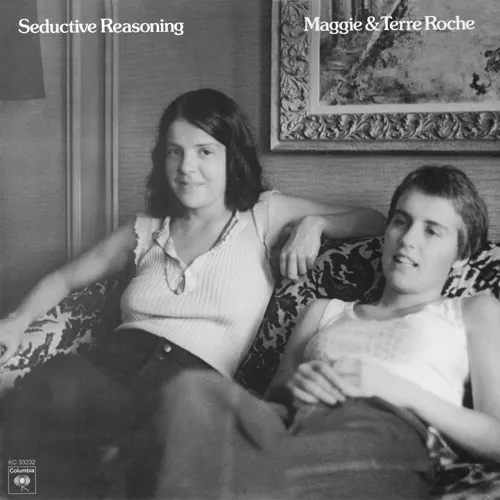

Over the years Maggie and I kept in touch with Chip as our paths crossed in significant ways. In 1975, we put out an album entitled Seductive Reasoning on Columbia Records. The record company wanted us to use a photo for the cover—a shot taken by a fashion photographer in which we wore black velvet attire and lots of makeup. We preferred a snapshot Chip took of us sitting on a couch in a hotel room in St. Louis (Figure 2.1). I’ve always thought Chip took the best photos of Maggie and me when we were starting out. There are some great ones from a visit he paid us when we lived in Greenwich Village in a studio apartment. I remember a photo he took of me cleaning the toilet. Chip never interfered with the moment at hand by suggesting we turn and pose for the camera.

Source: Cover photo by Chip Berlet, reprinted with permission. Album cover courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment, reprinted with permission.

We had to fight with the record company to use Chip’s photo—a hill we chose to die on! Years later when the record was reissued, it sported a brand-new cover taken by a fashion photographer, making the original cover with Chip’s photo a collector’s item that people cherish owning to this day.

Maggie, in particular, kept in touch with Chip over the years. She followed his work with Political Research Associates, and from time to time she would tell me about some fascinating situation he had brought to light in his newsletters. It seemed to me he turned over many a rock to expose the slimy curdling of some clandestine activity by an evil organization.

I was proud to know him! And am still. Thanks for asking me to participate in this tribute to Chip Berlet. What a great idea, whoever thought of it. I wish many more years of happiness for Chip as he enjoys all the good karma he has amassed in this life. Thank you, Chip, for inspiring me and so many others with your courageous example! And for being a fun guy to boot!

3 From way back when to now

Grace Mastalli

DOI: 10.4324/9781003137276-3

Where do I begin a festschrift essay to honor Chip Berlet? I am not an expert in his scholarly field and have no original research to contribute. Yet, mere inclusion in a tabula gratulatoria is inadequate. Chip Berlet has been my friend, colleague, intellectual influence, and political sparring partner for most of my life. The standard format doesn’t really suit the case of our intersecting and occasionally overlapping academic, professional, and personal lives—nor the importance of his close friend, the late Curt Koehler.

Where should I begin?

Do I start way back when we met on the empty school playground across from his Hillsdale, New Jersey, home? (I doubt he recalls when, as a Boy Scout, he pushed a lonely younger kid on a swing.) Should this piece begin when Chip, as a high school student, came to pay his respects at my father’s funeral? (Some things stick with you; I was a fifth-grader then, but I can still remember the look on Chip’s face and tell you the color of his necktie.)

The festschrift is a scholarly tradition, so perhaps I should start with my freshman year at Pascack Valley Regional High School where our attendance overlapped for a year. By then a genuine Eagle Scout, Chip had already distinguished himself by becoming the first National Merit Scholar to take five years to graduate high school. That extra year for Chip was a good thing for me because, if not for that anomaly, I might not be writing this. (He, it must be noted, did receive a high school diploma in June 1968—one degree that I never did manage to earn.)

Curt, meanwhile, was from the same New York City bedroom community, Hillsdale, as Chip and I. Curt’s mother called the three of us the “Three Musketeers.” In fact, Curt, whose full name was John Curtis Koehler, and Chip, né John Foster Berlet, were so close that for years they shared the nom de plume “John Kober.” Curt worked at the College Press Service and National Student Association with Chip and moved to Chicago soon after Chip did. A union and community organizer, victims advocate, and high school teacher, he died too young at fifty-six in 2007.

While we were still in school, the fall of 1967 found us protesting the demolition of a beloved historic farm for new housing by nouveau riche developers. The Revolutionary-era Clendenny buildings were torn down, but that local action whet our appetites for exercising our First Amendment rights on many other issues. I ran for freshman class vice president and lost. But encouraged, even egged on by Chip, I and others championed a variety of new school policies, including such radical changes as allowing girls to take shop class, wear slacks to school, and participate in all school clubs. The latter was especially important to me because my late father worked with the previously male-only Audio-Visual Club. That club’s room was where so many of the long conversations Chip and I had about love, war, politics, racism, sexism, and societal change began.

Listening to Chip talk about what it was like having a senior Army officer father and military school graduate, and active college ROTC brother, shattered many of my preconceptions. Without those conversations, I might never have understood, among other things, that aspects of the U.S. Armed Forces were quite progressive compared with my suburban New Jersey neighborhood. (For that matter, without those conversations, I might never have married my retired Navy officer husband!)

Being in high school with Chip during 1967 and 1968 was never boring. There were parties, canoe trips, and movie dates—but also experiments in activism and advocacy. (Cue the soundtrack of Simon and Garfunkel, James Taylor, and Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth.”)

By spring 1968, the Seniors knew whether they were headed to college or Vietnam. I found my way—more as observer than participant—to demonstrations and protest marches in New York City and Washington, DC. Curt, who I had come to think of as Chip’s alter ego, memorably skipped his prom and headed to Sweden for a World Council of Churches meeting, returning for a week-long Ecumenical Camp on Lake Winnipesaukee in New Hampshire before he headed to Columbia University and Chip to the University of Denver. (The camp, nicknamed “Winni,” became an annual event for several years with Chip and Curt involved in its leadership. It served up a multimedia platform for thinking about social change seasoned with music, theater, liberation theology, and interdenominational skinny dipping. Over the years, Winni remained a spiritual touchstone for many of us.)

When Chip and Curt left to attend college, they left me with reading suggestions that ranged from dystopian science fiction by Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, and Isaac Asimov, through the plays of Shakespeare and Tom Stoppard (Curt) and essays by Joan Didion and Tom Wolfe, as well as Marshall McLuhan’s The Medium is the Massage (Chip). By then, the student newspaper editor and aspiring print journalist, I was dismayed by how enthralled Chip was with McLuhan’s ideas, including “The media work us over completely”; “so pervasive are they in their personal, political, economic, aesthetic, psychological, moral, ethical and social consequences that they leave no part of us untouched, unaffected, or unaltered”; and “societies have always been shaped more by the nature of the media by which men communicate than by the content of the communication.”

Even as television news brought daily body counts and Richard Nixon into family living rooms I disagreed. I recall with embarrassment how strongly I argued with Chip that “content” always mattered much more than the means of communication, and while there might be a place for “New Journalism,” world leaders couldn’t be marketed like detergent. (Wishful thinking on my part, I now admit. He was right. I was very wrong.)

One semester into college, Chip, the budding sociologist, introduced me to Max Weber, Talcott Parsons, ...