eBook - ePub

Some Woman Had to Fight

The Radical Life of Sue Shelton White

Gay Majure Wilson

This is a test

Partager le livre

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Some Woman Had to Fight

The Radical Life of Sue Shelton White

Gay Majure Wilson

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

This biography explores the personal, political and professional life of Sue Shelton White, a militant suffragist, pioneering Tennessee lawyer and vocal leader in the controversial protests and tireless lobbying campaign for ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, granting women their equal right to vote 100 years ago.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Some Woman Had to Fight est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Some Woman Had to Fight par Gay Majure Wilson en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Law et Law Biographies. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

LawSous-sujet

Law BiographiesCHAPTER 1

Rowdyism About to Break Loose

In 1915 the world heaved under the strain of war and tragedy. World War I raged in Europe. The British ocean liner Lusitania was attacked and sunk by a German U-boat’s torpedo. A deadly hurricane struck Galveston for the second time in the new century, taking hundreds of lives and devastating the Texas coastline, while the menace of Typhoid Mary struck in New York.

There were moments of distraction and optimism. Babe Ruth hit his first home run. Americans witnessed the first coast-to-coast phone call, between Alexander Graham Bell in New York and his assistant Thomas Watson in San Francisco.

The year also brought suffrage gains for women in Denmark and Iceland.1,2 But women in the United States of America still were fighting for recognition of their right to vote.

In October 1915 the Tennessee Equal Suffrage Association held its state convention in Jackson, Tennessee, where 28-year-old Sue Shelton White worked as a stenographer, a job she had inherited from her older sister Lucy. Lucy had left behind small-town life for the glamor of being a newspaper reporter in San Francisco.

White was born 20 miles away in Henderson, Tennessee on May 25, 1887. Her father was a lawyer and preacher. Her mother taught music lessons to local children. Both died when White was young, thrusting the burdens of self-sufficiency upon young Sue and her siblings at an early age.3

White was named recording secretary of the Tennessee suffrage association at the 1915 convention. The local suffragists urged Tennessee state legislators to vote for equal suffrage, but also expressed appreciation to President Woodrow Wilson for endorsing voting rights for women.4 How things would change just two years later.

In November 1917 nationally known and often reviled suffragists Maud Younger and Mrs. Howard Gould drove across the American South on a lecture tour. Calling it the Dixie Tour, Younger and Gould lectured in the Southern states to promote the causes of the National Woman's Party (NWP). As they traveled, they were caught in the political crossfire over the NWP’s public protests in Washington, D.C. The Dixie Tour sought to defend the defiant protests, which were under attack as being unpatriotic during the crisis and horror of World War I.5

Younger was from California. Gould was from New York. Upon arriving in the South, they were strangers in a strange land. After stops in Alabama and Georgia, Younger and Gould headed to Tennessee.

Becky Hourwich Reyher was a young college student from New York who had married earlier that year. As an organizer for the NWP, she was one of several women sent ahead of Younger and Gould to the Southern states. This was Reyher’s first long trip away from home. Anger toward the NWP’s militant suffragists was mounting as she traveled through each state. “And now it was getting hot and sharp in Tennessee,” she reported.

Reyher arrived in Jackson, Tennessee to meet officials and arrange permission for the lecture stop in this small city in West Tennessee surrounded by cotton fields. “We had no Committee women in Jackson. . .I was entirely alone.”

Reyher had an appointment to meet the Jackson mayor. She stopped on a downtown street and asked “a nice, sweet looking woman” for directions. The local newspaper had carried Reyher’s photo and a story of her arrival. The woman recognized her: “You are one of the suffragists, aren’t you?” Reyher confirmed yes. The woman replied, “Good luck to you.”

Reyher later needed to dictate a report of her work and send it to renowned NWP leader Alice Paul. She went to the office of a public stenographer who the hotel staff had recommended: “Miss Sue, the best one in town.”

When Reyher arrived at the stenographer’s office, she was surprised to find that it was the same sweet, helpful woman she had spoken with earlier on the street — Sue Shelton White.

Reyher confided to White that the mayor was having doubts about allowing the lecture. Rumors were swirling that local residents were threatening trouble, with some demanding that the suffragists be run out of town. “Sue listened, her eyes flashing.”

White called the mayor and police chief. She demanded that the suffragist leaders be allowed to speak and that city officials protect them from harm. White assured the mayor that she could vouch for the suffragists and their message. She argued that these women simply were asking for the vote, and nothing about that could be called unpatriotic.

City officials relented and gave their permission.

Younger and Gould arrived in Jackson on November 22, 1917. Younger sported a flowing chiffon dress and decorative, wide-brimmed hat. Reyher later recalled, “The whole town was agog.”

That evening White spoke first to the audience of 250. Reyher recalled, “I was surprised to hear the deep rumble that came from that slender frame, or the passion and oratory with which her words rolled out.” White reminded the audience to show their Southern hospitality to the visitors. Two burly men walked the aisle ready to arrest troublemakers, with “the atmosphere of rowdyism about to break loose.”6

Younger spoke passionately about the federal suffrage amendment and defended the NWP’s tactic of picketing the White House.

After Younger’s lecture, the Jackson audience passed a resolution asking the mayor of Nashville, Tennessee to grant Younger permission to speak in his city. The resolution vouched that Younger had said nothing unpatriotic or disloyal about the United States or the President. It was signed by five leading citizens of Jackson: a banker, a newspaper owner and secretary of the Jackson Association of Commerce, an attorney, the chief of police, and meeting chairman Sue Shelton White.7

White is credited by Reyher with transforming the atmosphere of that controversial meeting. “She spellbound that hostile audience. The rumblings stopped, the atmosphere became friendly. . .We hated to leave Jackson.”

After the meeting, White told the suffragists she would accompany them and smooth the way on their tour through Tennessee. “And everywhere, thanks to her, the hostility vanished.”8

White relied on her work as a stenographer to make her living as a single woman in the early 20th century. By closing her office to join the suffragist tour, she knew that she was sacrificing the financial stability her job brought. It was the first of many risky career moves, of which White would say, “I am not afraid of starving.”9

When Reyher returned to Washington, she and Younger both told Alice Paul about White. “It was then Miss Paul began badgering Sue to come to Washington, and you know the rest,” Reyher wrote years later.10

That tense, unpredictable evening in her hometown marked White’s debut on the national suffragist stage.

CHAPTER 2

Every Mother’s Daughter

In 1917, during World War I, the National Woman’s Party was reviled by many for daring to stage militant protests in Washington, D.C. in a time of war.

Writing to a Tennessee newspaper in November 1917, White defended the White House pickets by the NWP, arguing that women of gentle breeding and high ideals were picketing on behalf of “their leader, Alice Paul, who is dying in the Occoquan Workhouse,”1 an odious place known for its brutal treatment and forced feedings of suffragist prisoners.

The newspaper editor replied, insisting that the NWP’s militant methods were costing the suffrage movement the empathy of the nation, at a time when the country faced its greatest crisis. The editor pointed to the ability of the other, quieter faction of the suffragists — the National Woman’s Suffrage Association — to “present their cause without ill feeling.”2

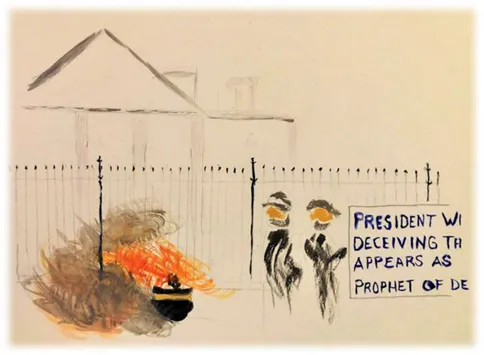

Less than two years later, on February 9, 1919, White was center stage in the protests. She was among almost 100 women who marched to the White House and gathered shoulder to shoulder around an urn. A curious crowd of several thousand people had gathered, standing for two hours, listening and watching the spectacle in anxious anticipation of what may come next.

A fire was lit. Flames leapt skyward. White held high the words of an unfulfilled pledge by President Wilson to extend democracy to women — then dropped the pledge in the fire — her anger burning at his empty promises. A cartoon three-foot paper effigy of Wilson also went up in flames.3

White and 64 other women were arrested by civil and military police. After the principal speaker Mrs. Henry O. Havemeyer was arrested, more women dashed to the podium to speak in her place. Each was grabbed and arrested as she made her desperate attempt. The women kept up their protests and shouted at spectators as they were shoved into patrol wagons.4

At the police station, the women refused to post bond and were jailed. White served five days in the filthy, harsh conditions of the Lorton Women’s Workhouse in Virginia.

The arrests of the suffragists brought mixed reactions in White’s hometown. The editor of a neighboring small-town newspaper complained:

The female nuisances who made themselves conspicuous and offensive by picketing the White House for the purpose of annoying the President and members of his cabinet are just where they ought to be—in jail—and should be allowed to remain there until they promise, and make bond if necessary, to go to their homes, where they are doubtless of minimum use—and God pity the men they go back to.5

The Tennessee Suffrage Association — the moderate faction of the suffragists — opposed the White House pickets, claiming they were unpatriotic.6

After her release, White joined other former prisoners aboard the Prison Special train tour in February and March 1919. It was a cross-country speaking tour by 26 former suffragist prisoners to publicize their brutal, unjust experience and recruit supporters for the NWP...