eBook - ePub

Contact Lens Practice E-Book

Nathan Efron

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Contact Lens Practice E-Book

Nathan Efron

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

In this thoroughly revised and updated third edition of Contact Lens Practice, award-winning author, researcher and lecturer, Professor Nathan Efron, provides a comprehensive, evidence-based overview of the scientific foundation and clinical applications of contact lens fitting. The text has been refreshed by the inclusion of ten new authors – a mixture of scientists and clinicians, all of whom are at the cutting edge of their specialty. The chapters are highly illustrated in full colour and subject matter is presented in a clear and logical format to allow the reader to quickly hone in the desired information.

- Ideal for an optometrist, ophthalmologist, orthoptist, optician, student, or work in the industry, this book will serve as an essential companion and guide to current thinking and practice in the contact lens field.

- Highlights of this edition include a new chapter on myopia control contact lenses, as well are completely rewritten chapters, by new authors, on keratoconus, orthokeratology, soft and rigid lens measurement and history taking.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Contact Lens Practice E-Book est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Contact Lens Practice E-Book par Nathan Efron en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Medizin et Augenheilkunde & Optometrie. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Part 1

Introduction

1

History

Nathan Efron

Introduction

We cannot continue these brilliant successes in the future, unless we continue to learn from the past.

Calvin Coolidge, inaugural US presidential address, 1923

Coolidge was referring to the successes of a nation, but his sentiment could apply to any field of endeavour, including contact lens practice. As we continue to ride on the crest of a huge wave of exciting developments in the 21st century, we would not wish to lose sight of the past. Hence the inclusion in this book of this brief historical overview.

Outlined below in chronological order (allowing for some historical overlaps) is the development of contact lenses, from the earliest theories to present-day technology. Each heading, which represents a major achievement, is annotated with a year that is considered to be especially significant to that development. These dates are based on various sources of information, such as dates of patents, published papers and anecdotal reports. It is recognized, therefore, that some of the dates cited are open to debate, but they are nevertheless presented to provide a reasonable chronological perspective.

Early Theories (1508–1887)

Although contact lenses were not fitted until the late 19th century, a number of scholars had earlier given thought to the possibility of applying an optical device directly to the eyeball to correct vision. Virtually all of these suggestions were impractical.

Many contact lens historians point to Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex of the Eye, Manual D, written in 1508, as having introduced the optical principle underlying the contact lens. Indeed, da Vinci described a method of directly altering corneal power – by immersing the eye in a bowl of water (Fig. 1.1). Of course, a contact lens corrects vision by altering corneal power. However, da Vinci was primarily interested in learning the mechanisms of accommodation of the eye (Heitz and Enoch, 1987) and did not refer to a mechanism or device for correcting vision.

In 1636, René Descartes described a glass fluid-filled tube that was to be placed in direct contact with the cornea (Fig. 1.2). The end of the tube was made of clear glass, the shape of which would determine the optical correction. Of course, such a device is impractical as blinking is not possible; nevertheless, the principle of directly neutralizing corneal power used by Descartes is consistent with the principles underlying modern contact lens design (Enoch, 1956).

As part of a series of experiments concerning the mechanisms of accommodation, Thomas Young, in 1801, constructed a device that was essentially a fluid-filled eyecup that fitted snugly into the orbital rim (Young, 1801) (Figs. 1.3 and 1.4). A microscope eyepiece was fitted into the base of the eyecup, thus forming a similar system to that used by Descartes. Young’s invention was somewhat more practical in that it could be held in place with a headband and blinking was possible; however, he did not intend this device to be used for the correction of refractive errors.

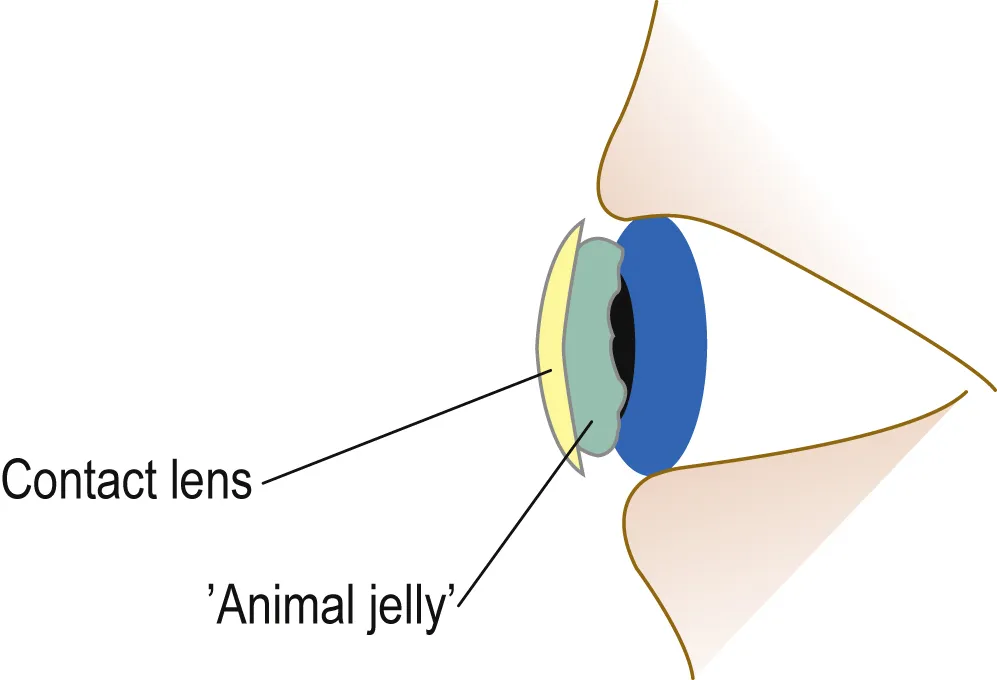

In a footnote in his treatise on light in the 1845 edition of the Encyclopedia Metropolitana, Sir John Herschel suggested two possible methods of correcting ‘very bad cases of irregular cornea’: (1) ‘applying to the cornea a spherical capsule of glass filled with animal jelly’ (Fig. 1.5), or (2) ‘taking a mould of the cornea and impressing it on some transparent medium’ (Herschel, 1845). Although it seems that Herschel did not attempt to conduct such trials, his latter suggestion was ultimately adopted some 40 years later by a number of inventors, working independently and unbeknown to each other, who were all apparently unaware of the writings of Herschel.

Fig. 1.1 Idea of Leonardo da Vinci to alter corneal power.

Fig. 1.2 Fluid-filled tube described by René Descartes.

Fig. 1.3 Eyecup design of Thomas Young.

Fig. 1.4 Thomas Young.

Fig. 1.5 ‘Animal jelly’ sandwiched between a ‘spherical capsule of glass’ (contact lens) and cornea, as proposed by Sir John Herschel.

Glass Scleral Lenses (1888)

There was a great deal of activity in contact lens research in the late 1880s, which has led to debate as to who should be given credit for being the first to fit a contact lens. Adolf Gaston Eugene Fick (Fig. 1.6), a German ophthalmologist working in Zurich, appears to have been the first to describe the process of fabricating and fitting contact lenses in 1888; specifically, he described the fitting of afocal scleral contact shells first on rabbits, then on himself and finally on a small group of volunteer patients (Efron and Pearson, 1988). In their textbook dated 1910, Müller and Müller, who were manufacturers of ocular prostheses, described the fitting in 1887 of a partially transparent protective glass shell to a patient referred to them by Dr Edwin Theodor Sämisch (Müller and Müller, 1910). Pearson (2009) asserts that the fitting was done by Albert C Müller-Uri. Fick’s work was published in the journal Archiv für Augenheilkunde in March 1888, and must be accorded historical precedence over later anecdotal textbook accounts.

French...