eBook - ePub

Companion to Psychiatric Studies E-Book

Eve Johnstone, David G. Cunningham-Owens, Stephen Lawrie, Andrew McIntosh, Michael D. Sharpe

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 864 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Companion to Psychiatric Studies E-Book

Eve Johnstone, David G. Cunningham-Owens, Stephen Lawrie, Andrew McIntosh, Michael D. Sharpe

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

* 2011 BMA Book Awards - Highly Commended in Psychiatry *

A new edition of a classic textbook now published for the first time with colour. Covering the entire subject area [both basic sciences and clinical practice] in an easily accessible manner, the book is ideal for psychiatry trainees, especially candidates for postgraduate psychiatry exams, and qualified psychiatrists.

- New edition of a classic text with a strongly evidenced-based approach to both the basic sciences and clinical psychiatry

- Contains useful summary boxes to allow rapid access to complex information

- Comprehensive and authoritative resource written by contributors to ensure complete accuracy and currency of information

- Logical and accessible writing style gives ready access to key information

- Ideal for MRCPsych candidates and qualified psychiatrists

- Expanded section on psychology – including social psychology – to reflect the latest MRCPych examination format

- Discussion of capacity and its relationship to new legislation

- Text updated in full to reflect the new Mental Health Acts

- Relevant chapters now include discussion of core competencies and the practical skills required for the MRCPsych examination

- Includes a section on the wider role of the psychiatrist – including teaching and supervision, lifelong learning, and working as part of a multidisciplinary team (including dealing with conflict, discipline and complaints)

- Includes new chapter on transcultural aspects of psychiatry

- Enhanced discussion of the use of the best current management options, both pharmacological and psychotherapeutic, the latter including CBT (including its use in the treatment of psychosis) and group, couple and family therapy.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Companion to Psychiatric Studies E-Book est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Companion to Psychiatric Studies E-Book par Eve Johnstone, David G. Cunningham-Owens, Stephen Lawrie, Andrew McIntosh, Michael D. Sharpe en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Medicine et Psychiatry & Mental Health. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

1 An introduction to psychiatry

Early concepts

Psychiatric disorders have a long history. Early Egyptian papyri and the Old Testament contain references to mental disturbances. Mental disorders received extensive discussion in Ancient Greek medical texts, and authors such as Hippocrates (Jones 1972) and Aretaeus (Adams 1856) appeared to regard them as having bodily causes and requiring medical treatment. The concept of melancholia as described by Aretaeus has obvious similarities to our current concept of severe depression, and a link between morbid depression and morbid elevation of mood was clearly appreciated at that time.

While it is possible to link such descriptions over gaps of centuries, it is important to recognise that the conceptual framework for psychopathological descriptions has changed greatly over the years. The meanings of terms used to describe diagnostic concepts and behaviours may vary considerably from time to time, so that the assumption that terms such as ‘mania’, ‘melancholia’ and ‘hypochondria’ mean the same now as they did even two centuries ago may not be justified.

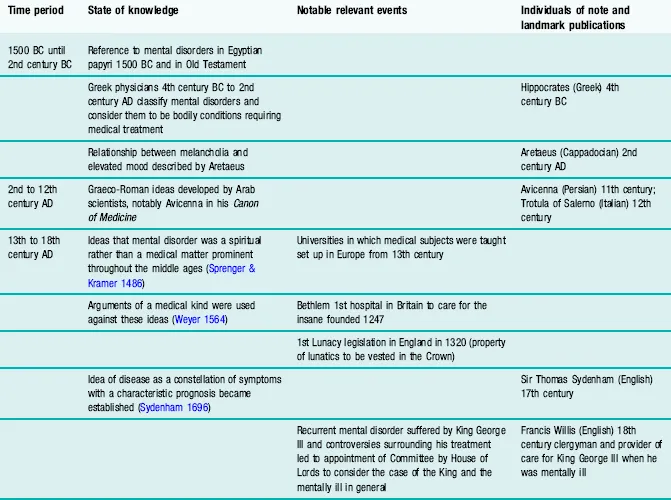

Whether or not the syndromes that were described in the ancient world closely resemble those which we see now, it is evident that mental disorders have been studied since Graeco-Roman times. The work ascribed to Hippocrates (4th century BC) was followed by that of Celsus, Aretaeus and Galen, writing in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. The Graeco-Roman heritage was developed by Arab scientists, notably Avicenna, the Persian physician who, in the 11th century, developed Galen’s ideas in his Canon of Medicine. A brief summary of what is known of Indo-European understanding of psychiatry from ancient times until the 18th century is given in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Ancient times until 18th century

The middle ages to the modern era

Universities in which medical subjects were taught were set up in Europe from the 13th century, and some development of these ideas continued. However, mental disorder was largely seen as a spiritual rather than a medical problem throughout the Middle Ages (Sprenger & Kramer 1486). Lunacy legislation in England dates from 1320, when it was enacted that the property of lunatics should be vested in the Crown. Bethlem, the first hospital in the British Isles to care for the insane, was founded in 1247. The humoral tradition of the Greeks was maintained in Europe, and detailed accounts from this point of view were written in French and in English, most notably by Robert Burton in his Anatomy of Melancholy (Burton 1621).

Sydenham’s (1696) work was a landmark on the road towards modern medicine. In the ancient world symptoms and signs, such as fever and joint pains, were themselves regarded as diseases to be studied separately, and it was only with Sydenham’s work that the idea of disease as a syndrome or constellation of symptoms having a characteristic prognosis became established. This laid the foundation for the rational diagnosis and classification of disease.

As far as psychiatry in Britain was concerned, the recurrent mental disorder suffered by King George III in the 18th century had the benefit of arousing public interest and the House of Lords appointed a committee to institute a detailed enquiry. This considered the treatment of the King’s illness, but also the care of the mentally ill throughout the country (Henderson & Batchelor 1962).

The modern era – the 18th century to the present day

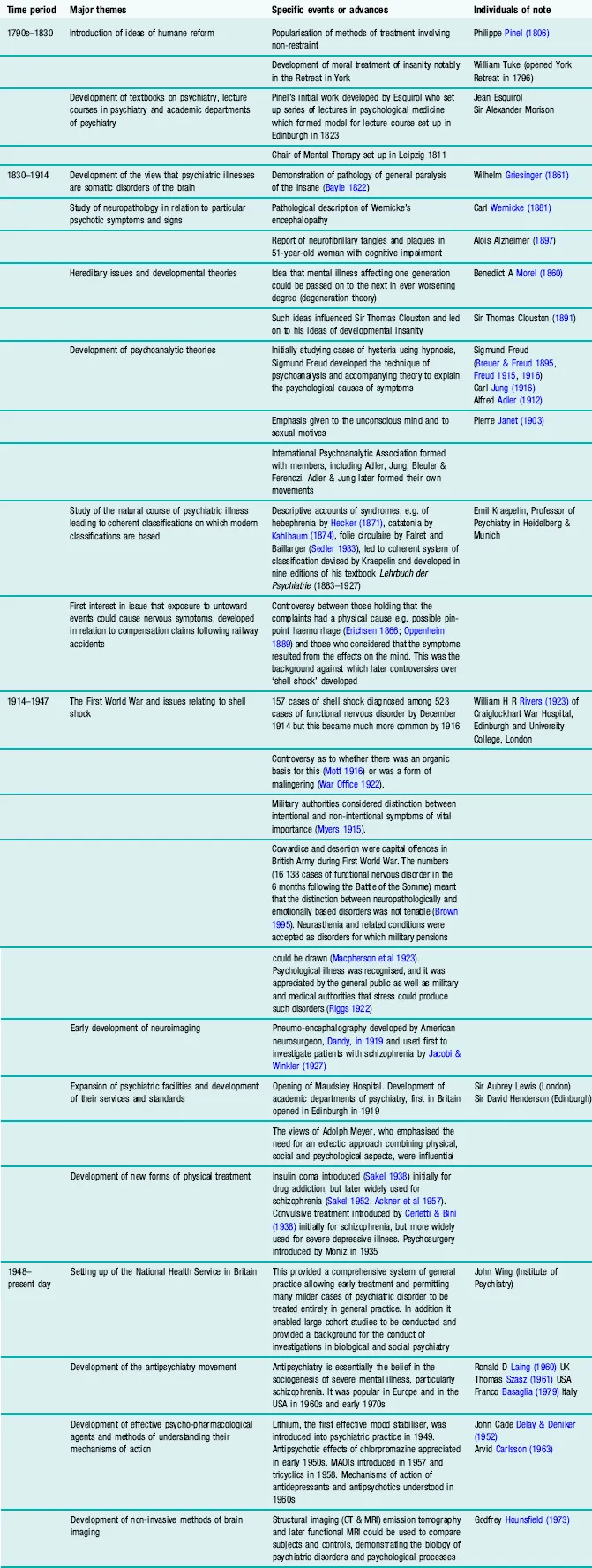

The main developments in psychiatry in the Western world from the 18th century until the present time are summarised in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 The modern era – 18th century until the present day

The first major development was the period of humane reform. Philippe Pinel, working at the Bicêtre Hospital in Paris, wrote extensively on psychiatric subjects (Pinel 1806) and popularised methods of treatment involving non-restraint. So-called ‘moral treatment’ of the insane began in Britain in the Retreat at York, opened in 1796, and similar programmes of care were instituted in the new lunatic asylums that were being built in the first half of the 19th century. These replaced the private madhouses, which had, until then, provided care for the mentally disordered. In 1792, Andrew Duncan, Professor of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh, sponsored an appeal for funds to establish the Royal Edinburgh Mental Hospital, which was opened in 1813.

In 1808 a Bill to provide ‘better care and maintenance of lunatics being paupers or criminals in England’ was introduced. A series of amendments of the subsequent Act in 1811, 1815, 1819 and 1824 was followed by the establishment of the Lunacy Commission in 1845, which later, in 1913, became organised as the Board of Control. The powers of this Board were dissolved in England at the time of the introduction of the Mental Health Act 1959, but were resurrected in 1983 in the form of the Mental Health Act Commission.

The development of academic psychiatry

European academic psychiatry began in France with the work of Pinel but it was in Germany that psychiatry first became established as a subject for academic study in universities. Griesinger was appointed first Professor of Psychiatry and Neurology in Berlin in 1865 and developed a department for the study of mental disorders. This work involved clinical and pathophysiological research based upon the hypothesis that ‘mental illness is a somatic illness of the brain’ (Griesinger 1861).

With the development of academic departments, the study of psychiatric disorder flourished in Germany. The first important theme was the natural course of mental disorders as studied by Kahlbaum and Kraepelin. It was largely on the basis of outcome studies that Kraepelin developed his comprehensive classification of mental illness which is the foundation of the schemes now in use throughout the world. Kraepelin, Professor of Psychiatry in Heidelberg, and later in Munich, wrote nine editions of his Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie, published between 1883 and 1927. He was concerned to move away from the earlier 19th century nosological concepts which he criticised as unreliable from a clinical and prognostic point of view (Hoff 1995). In the fifth and sixth edition Kraepelin developed the concept of dementia praecox (later more commonly known by Bleuler’s term of schizophrenia) and its separation, with a poor prognosis, from manic-depressive insanity, with a good, or at least a better, prognosis. In defining dementia praecox he drew together hebephrenia as described by Hecker (1871), catatonia as described by Kahlbaum (1874) and his own dementia paranoides, regarding them as manifestations of the same disorder with an onset in early adult life and a poor outcome.

Another major theme was the relationship of mental disorder to brain pathology. Griesinger’s ideas stimulated this work, but it was greatly encouraged by the progress that was being made in identifying pathological lesions in neurological disorders: for example, general paralysis of the insane which had been described by Bayle (1822) under the title ‘arachnitis chronique’. Neuropathological approaches to dementia were also successful. In 1881, Wernicke published a description of the encephalopathy which was named after him, and Alzheimer in 1907 reported neurofibrillary tangles, plaques and other changes in a 51-year-old woman with cognitive impairment and psychotic features.

A further theme of early research concerned hereditary issues. This developed from the work of Morel (1860), who proposed what came to be known as the theory of degeneration. Although hereditary taint had been mentioned in relation to insanity before this time, it was highlighted by Morel’s work. His degeneration theory involved the idea that mental illness affecting one generation could be passed on to the next, in ever worsening degree (Berrios & Bear 1995). As the hereditary taint was thought to be behavioural as well as physical, stigmata of degeneration, such as deformed teeth and ears, were assessed (Talbot 1898). The notion that behaviours such as alcohol abuse and masturbation could promote degeneration was included in the general theory.

These ideas influenced Sir Thomas Clouston (1890), who in addition put forward the concept of developmental insanity and considered that the results of his investigations of palatal structure in adolescent insanity (which he saw as being part of Kraepelin’s disease entity of dementia praecox) demonstrated that this disorder represented a form of developmental defect of ectodermal tissue (Clouston 1891).

It was partly as a reaction to the pessimistic and unsympathetic view of the mentally ill put forward by the degeneration theories that an increasing interest in psychological causes of mental disorder developed from the end of the 19th century.

Psychoanalytic theories

Sigmund Freud began his career in neurological research and visited Charcot in Paris with a view to learning about the use of hypnotism in cases of hysteria. He developed the alternative method of free association in which patients were encouraged to speak without distraction about what was in their mind. Although initially intended as a treatment, Freud used this technique to develop an understanding of the psychological causes of these disorders. He went on to develop his own ideas about the importance of childhood experience in the behaviour of adults and the part played by the unconscious and irrational parts of the mind in influencing behaviour. He gave emphasis to sexual motives as determinants of symptomatology....