1 Philosophers’ walks

There are many places called “Philosopher’s Walk.” When I arrived in Toronto to pursue a PhD in philosophy, I was delighted to find a Philosopher’s Walk that runs through a ravine into the University of Toronto’s main campus. In summer and spring, it’s a green and relatively secluded refuge; I often walked there to think or to ease my mind. In what was formerly Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia), a more famous Philosopher’s Walk commemorates the walk Immanuel Kant took every day beginning at 5 o’clock sharp, so unvaryingly that housewives supposedly set their clocks by it.1 Equally famous is the Philosopher’s Walk in Kyoto, where the 20th-century philosopher Kitaro Nishida walked every day on his way to the university.

The philosophers’ walks in this book are of a different type. I’m particularly interested in how walking and thinking intersect in the work of certain philosophers and writers. Some of them—René Descartes, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir—are well known as philosophers, although the connection of walking to their thought has been less remarked upon. Others—Søren Kierkegaard, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Friedrich Nietzsche—are famous for the importance they placed on walking for their philosophical thought. A third group consists of writers of a philosophical bent, such as André Breton and Virginia Woolf, and another, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who was both a philosopher and a poet. I walked in their footsteps, in cities, fields, and forests, on mountain trails and level plains, in the hope of gaining some insight into the connection between their walking and their thinking. This book is the record of those “philosophers’ walks” and the thoughts they inspired.

I take “thinking” to include not just philosophical reasoning, but also sensory perception, memory, and imagination. Using walking to investigate these mental phenomena, I examine the relation of our mental life to our bodily existence, or “the mind-body problem,” as it’s come to be known. Although I deal most explicitly with this topic in Chapter 2, on the 17th-century philosopher René Descartes and his contemporary, Pierre Gassendi, the theme runs through the whole book. It might seem obvious that sensation and sense perception involve the body as much as the mind. My experience of walking in the footsteps of philosophers has led me to the view that so do memory, imagination, and conceptual thought. The style of some thinkers—Rousseau, Coleridge, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche—is inseparable not only from their embodied experience, but from their activities as walkers, and that holds true even for their most “intellectual” thoughts. As they walked, so they thought.

That being so, the best way to get inside their thinking processes would be to walk in their footsteps. Often, walking in someone’s footsteps is a kind of pilgrimage, a way of paying tribute to a writer, and a means of trying to feel closer to that person, and sometimes walking tours fall to the level of a tourist gimmick. In the case of most of the thinkers discussed in this book, however, their way of relating to their physical and social environments through walking formed so much a part of the very texture of how they experienced the world that it seemed to me that I would have to walk their walks in order to think their thoughts. Without climbing up and down trails in the Swiss Alps, Nietzsche would never have developed the perspectivism characteristic of his philosophy; without walking over the South Downs of East Sussex, Virginia Woolf would never have achieved the vision of an all-encompassing life-force expressed in novels such as Mrs Dalloway. Without walking in their footsteps, I could not hope to understand how any of them thought and wrote.

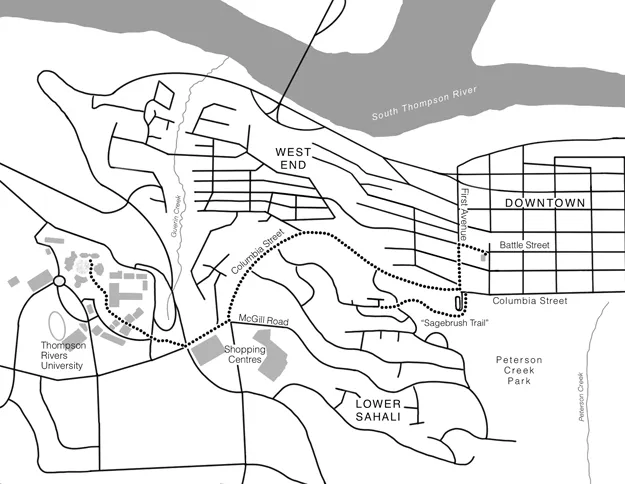

These are large claims, and I hope to make good on them in what follows. Each chapter involves a walk: my own regular walk in Kamloops in this chapter, and then walks either literally in the footsteps of an author (Breton, Coleridge, Rousseau, Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Woolf) or through the intermediary of their works (Sartre, Beauvoir). The methods I use vary: phenomenology when dealing with my own walks and those of Sartre and Beauvoir; Surrealism when discussing Breton’s walks; psychogeography and Walter Benjamin’s theory of the flâneur when discussing Kierkegaard’s walks in Copenhagen; German Idealism when discussing Coleridge. In each case, I have tried to understand the writer as the writer understands him- or herself.

I develop the theme of the connection between walking and thinking in stages. I begin in this chapter with my own walks in Kamloops as a way of sketching out the theme of walking as an active, embodied form of knowing. Chapter 2 develops this theme by looking at the debate between Descartes and Gassendi about whether the mind can function independently of the body. Gassendi argued that it cannot, and I use my experience of a mountain walk I took near Gassendi’s home town of Digne-les-Bains (France) to lend support to Gassendi’s position that mind and body are inseparable. In Chapter 3, I investigate how memory can be embodied, not just in the brain, but in the material environment. I retraced André Breton’s footsteps in 1920s Paris in order to see whether the material traces Breton left behind can be reactivated and “remembered” through walking. I argue that they can, and that this allows for the possibility of “remembering” someone else’s experiences—a conclusion that looks startling on the face of it, but which I will try to make sense of.

Chapter 4 looks at two crucial sections of Sartre’s existentialist magnum opus, Being and Nothingness: the sections dealing with vertigo and with what Sartre calls the “original project”—one’s choice of how one relates to the world and to oneself. I argue that Sartre’s use of walking to illustrate his ideas concerning freedom, anxiety, and selfhood cannot be regarded as incidental; the vividness of the descriptions of walking a mountain path makes it clear that Sartre is drawing from his own experiences. Sartre was happiest in the city, and I use Sartre’s theory of the original project to contrast Sartre’s negative attitude towards walking in the countryside with Beauvoir’s enthusiasm for hiking and mountain climbing, a difference in attitude that reflects their different ways of relating to their own bodies. Often wrongly regarded as a Cartesian dualist who separates mind from body, Sartre’s examples and theories tend to show on the contrary that even our most fundamental freedom is embodied.

If even mental freedom is embodied, then the same would hold for that freest of mental faculties, the imagination. In Chapter 5, I walk in the footsteps of Samuel Taylor Coleridge in Somerset, England to explore the relationship between walking and the poetic imagination in poems such as “This Lime-tree Bower My Prison.” I use Coleridge’s philosophical theory of the imagination and its sources in German Idealism (Kant and Schelling) to show that the poetic imagination, like walking, involves a synthesis over time of different perspectives, making the imagination as necessarily embodied as sense perception or memory.

Taken together, the first five chapters of the book build up a theory of walking as a form of embodied thinking, perceiving, knowing, remembering, and imagining. Chapters 6–8 explore this theory in relation to four different thinkers: Kierkegaard, Rousseau, Nietzsche, Woolf. For these thinkers, their style of thought is entirely of a piece with their style of walking.

Kierkegaard, the subject of Chapter 6, is famous as “the flâneur of Copenhagen,” a supposed “idler” who would walk all over town, conversing with people from all walks of life. My purpose in this chapter is to revisit the scene of Kierkegaard’s psychological observations of others in order to investigate his key thesis—expressed in works from Fear and Trembling to The Sickness Unto Death—that the outwardly observable aspects of a person are “incommensurable” with that person’s inner life. In a sense, my experiment involves a paradox (and Kierkegaard loved paradoxes): I would be using an outward behaviour (walking) in an external setting (Copenhagen) to explore the impossibility of getting inside someone’s inner, mental life through its outward aspects. Whether this paradox is an impasse, or whether, appearances to the contrary, it still allows for a deeper insight into Kierkegaard’s way of thinking, is a question I leave for the reader to decide—in keeping with Kierkegaard’s own approach to writing, which always aimed to throw the reader back on her own “inwardness” to answer the great questions of life.

Chapters 7 and 8, although involving long walks and explorations of the thoughts and writings of Rousseau, Nietzsche, and Woolf, are in many ways more straightforward. For in the case of these three writers and thinkers, the relation of walking to what they thought, and how they thought, is something that they themselves reflect on, at length and in depth. Rousseau famously declares, “I can only meditate when I am walking. When I stop, I cease to think; my mind works only with my legs… My body has to be on the move to set my mind going.”2 But the walking that stimulated Rousseau’s meditative thought required a particular setting: forests and mountains, away from other people, in fresh air and solitude. In that, Rousseau provided the model for generations of Romantic walkers, from Nietzsche to Virginia Woolf, who found solace and inspiration as solitary walkers in nature. For Nietzsche, the mountains of the Upper Engadine in Switzerland were, by his own estimation, the source of his greatest thoughts. And although Virginia Woolf is famous—mostly on account of her novel, Mrs Dalloway—as the great flâneuse of London, she would draw much of the worldview expressed in her novels from her solitary walks over the South Downs, where she could immerse herself in the creative and healing powers of the natural landscape.

Finally, in Chapter 9, I take look back over the ground covered and offer some further reflections on the connection between walking and thinking.

As is probably plain by now, this book weaves together multiple strands: the thoughts and lives of the people I discuss, together with my own walks. Because of the multidisciplinary nature of my investigation, I will often be straying into domains in which others have far more expertise than I do. Rebecca Solnit points out that “Walking is a subject that is always straying” through different domains of knowledge.3 I can only hope that if I sometimes stray off the path, Breton’s walking companion, Nadja, is right when she says: “Lost steps? There’s no such thing.”4 In following this multidisciplinary path, I am taking a route laid out 20 years ago by Solnit’s Wanderlust that has been followed by many writers since then. If anything separates my journey from theirs, it is the depth with which I explore the relation between walking and thought in the philosophers and writers in this book.

This is a book for readers who can take their time, who can stroll along with me and the writers I discuss. I’ve been guided on my way by some outstanding contemporary writers on walking: Rebecca Solnit, Lauren Elkin, Mary Soderstrom, Joseph Amato, David Le Breton, Frédéric Gros, Jean-Louis Hue, Phil Smith, Dan Rubinstein, Robert Macfarlane, Nan Shepherd, Karen Till, Alyson Hallett, Jo Vergunst, Tim Ingold, and Michel de Certeau. Voices from the past—Dorothy Wordsworth, Robert Louis Stevenson, William Hazlitt, Henry David Thoreau, Charles Baudelaire, Walter Benjamin, Guy Debord—kept me company along the way. You will meet them all en route.