![]()

CHAPTER 1

Diplomats in Search of a Government

November 1917–September 1918

The Russian Revolution and Russian Officials Abroad

The last time the chief of the Russian mission in Mexico, Vladimir Vendgauzen, received his trimesterly advance from the Russian Foreign Ministry was in September 1914. For five years, as he complained to the Foreign Ministry at Omsk in September 1919, he had been forced to rely on his savings. Now that they were exhausted, he asked for instructions as to how to close the mission and where to secure its archive and other government property.1

As Vendgauzen’s experience suggests, the year 1917 did not in itself mark the beginning of a crisis for Russian diplomacy. The collapse of the Russian Provisional Government and the civil war that followed were the continuation and deepening of a crisis that, it might be said, had begun in July 1914, grown arithmetically over 1915 and 1916, and geometrically from 1917 on, reaching its peak in the period from the Bolshevik seizure of power in November 1917 to the evacuation of General Vrangel’s Russian army from the Crimea in November 1920. This crisis was marked by the steady erosion of Russian influence and even sovereignty during the First World War, along with the perceptible narrowing of its diplomatic interests to exclude everything not directly connected with the war effort. In 1917, however, the external cause of the crisis, the war with the Central Powers, combined with an internal development, the revolution, to produce an altogether unprecedented situation.

The central government had collapsed, leaving its representatives abroad—ambassadors, ministers, consuls, and a large number of other official agents—in a state of limbo. This situation had, of course, a precedent in the February Revolution (March in the Gregorian calendar), but then the problem had been resolved by the swift recognition of the Provisional Government. In November 1917 no such resolution would be forthcoming. Russian representatives abroad would be forced to rely on their own initiative in weathering the storm.

When Vasilii Alekseevich Maklakov presented himself at the Quai d’Orsay on November 7, 1917,2 as Russia’s new ambassador to France, he was met with the news that the government that had appointed him was no more. Unable to present his diplomatic credentials on that day, he arranged with the French foreign minister, Jean-Louis Barthou, to return after the Bolshevik disturbance in Petrograd had been quelled and the Provisional Government restored to power.3 This return visit was never to take place.

Despite the fact that Maklakov could not be officially recognized as Russian ambassador, he was able to reach a modus vivendi with Barthou’s successor, Stephen Pichon, to be the unofficial chief representative of Russia in France, with the embassy nominally headed by the chargé d’affaires ad interim, Matvei Markovich Sevastopoulo. While in French diplomatic lists the post of Russian ambassador was left blank, Maklakov corresponded and met with French and other foreign officials and continued to perform his duties as ambassador de facto until French recognition of the Soviet government in 1924.4

In this manner, Maklakov’s position, though visibly weak, was solidified through the French government’s original assumption of the temporary nature of Bolshevik rule. The positions of Russian representatives in other countries occupied the entire spectrum of variations on the same theme. Among the strongest was that of Boris Aleksandrovich Bakhmeteff in Washington, DC. Appointed in the summer of 1917 by the Provisional Government, he immediately created a favorable impression in the United States, particularly in comparison to his predecessor and political antithesis, Georgii P. Bakhmet’ev.5

Bakhmeteff was, like Maklakov, a Constitutional Democrat. But unlike Maklakov, he had held a position in the Provisional Government as deputy minister of trade and industry. In his youth as a Menshevik, he never let politics get in the way of the more practical concern of education; prior to the First World War, he achieved international recognition as a professor of hydraulic engineering at the Institute of Transportation and St. Petersburg Polytechnic. When the First World War began, therefore, he seemed a natural choice to head the Central Military-Industrial Committee’s purchasing operations in the United States. Coupled with a good command of the English language and previous trips to America as an exchange student and scholar, his experience in this capacity led the government to appoint him to head a Russian mission to America in reply to the Root Mission to Russia in 1917.6 A strong advocate of closer Russo-American ties, Bakhmeteff found himself in an advantageous position when he arrived in the United States on June 15, 1917—Georgii P. Bakhmet’ev, a monarchist unwilling to serve the Provisional Government, had resigned in April and Russia found itself without an ambassador in Washington. The choice of Bakhmeteff to replace him was most fortunate, for Bakhmeteff’s liberal sentiments appealed as much to the American people at large, whom he addressed in a cross-country speaking tour, as they did specifically to one of President Wilson’s closest advisers, Colonel Edward M. House, and thus to the president himself.7

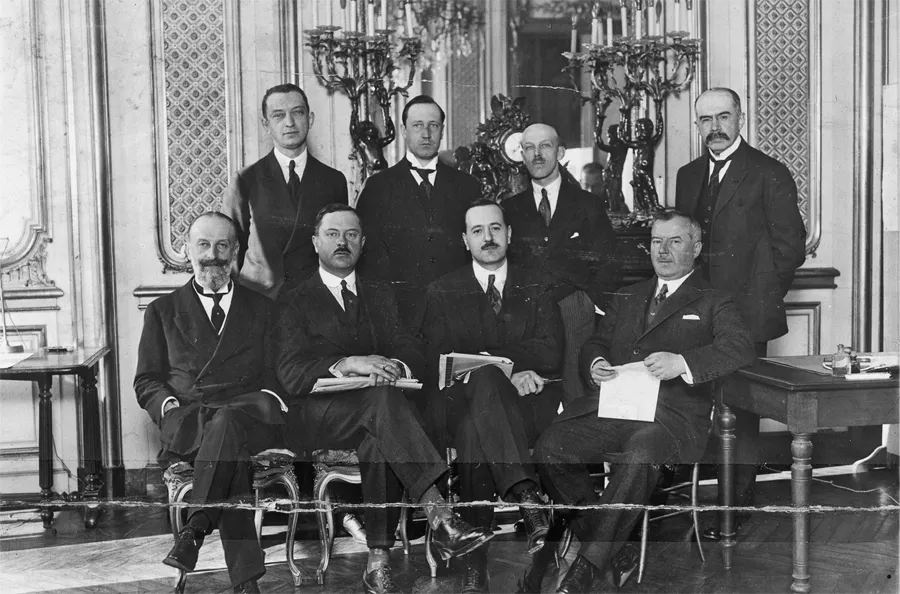

Personnel of the Russian Embassy in Paris, 1919. Hoover Institution Archives, Nikolai Bazili papers, box 30, envelope F.

Vasilii Alekseevich Maklakov, last Russian ambassador to France (undated). Hoover Institution Archives, Boris Nicolaevsky collection, box 813, envelope F.

Boris Bakhmeteff, last Russian ambassador to the United States, at his retirement in 1922. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-F8–19164 [P&P], National Photo Company Collection, https://www.loc.gov/item/2016832942/.

America’s twenty-eighth president, Woodrow Wilson, had been a professor of political science and later president of Princeton University, but this experience prepared him little for the realm of international politics the United States entered with its declaration of war against Germany in April 1917. America entered the war at a critical time, as the February 1917 revolution in Russia had resulted in a weakening of military discipline and decreased Russia’s contribution to the war effort. Wilson himself had little clue about Russia—a state that was only peripheral to US interests until 1917—until he was forced to deal with the consequences of the revolution there and the implications for Europe, the war effort, and the broader stability of Western civilization posed by Bolshevism. In 1918, prior to deciding on intervention, he met with two unofficial representatives who beseeched him to take action: Maria Bochkareva, of simple peasant origin and commander of Russia’s first Women’s Battalion of Death, and Prince L’vov, a bastion of Russia’s politically liberal, yet essentially conservative, aristocracy. Ultimately, Wilson fell back on his own experience and set of strictly American political views that were of little use in understanding, let alone dealing with, the situation in Russia. Wilson’s role in setting goals and methods for US intervention in the Russian Civil War has been hotly contested by historians, but whatever his purposes for intervening, the subsequent involvement of American troops did little to bring any measure of resolution to the conflict.

Edward Mandell House was President Wilson’s closest adviser on European affairs, although the Texas businessman’s actual European experience was very limited, confined to a brief period of education in England in his youth. Nevertheless, House stood behind many of Wilson’s most significant foreign policy initiatives, such as his “Fourteen Points” peace proposal and later the plan for the League of Nations. Like Wilson, he espoused liberal views on international affairs; in particular, he was inclined to favor recognition of new nation-states. The true extent of his influence on Wilson in Russian affairs is difficult to judge. Like the president, he was confused by the Russian situation and came to it inclined to apply American liberal and democratic ideals and methods, but these were scarcely tenable in the context of a civil war fueled by ideology. At the same time, House had a deeply ingrained fear of Russian domination of Europe. This concern was great enough that he consistently supported a strong Germany as “necessary to the economic stability of Europe and the welfare of the world.”8 This fear appears to have informed much of his advice to Wilson with regard to Russian and European issues.

When the Bolsheviks took power, Bakhmeteff had not only official status and moral authority to fall back on, but also a degree of control over significant financial and material resources, in the form of military supplies and the credits the United States government had advanced to Russia for their purchase. Both the supplies and the credits were later to become the stuff of legend, as well as a source of rumors and conflict for the various groups and individuals seeking to control them.

Equally firm, if not as financially independent and influential, were the positions of Mikhail Nikolaevich Girs and Vasilii Nikolaevich Krupenskii, the ambassadors to Italy and Japan, respectively. Capable and seasoned diplomats both, they were holdovers from the tsarist regime who were quite competent in the international and domestic politics of their geographic regions. Krupenskii, moreover, was the doyen of the diplomatic corps of Tokyo, which meant that up to 1920 all the newly appointed representatives to Japan had to present themselves to him.9

With respect to the major powers, only in Great Britain was the diplomatic situation more ambiguous than in France. Deprived of an ambassador since the death of Count Alexander Benckendorff in January 1917, the Russian embassy had felt its authority in Britain wane even more quickly than the authority of the government it represented. The lengthy delay in appointing an ambassador, which involved several botched attempts throughout the year, drained the prestige of the embassy, headed by its counselor, Konstantin Dmitrievich Nabokov, as chargé d’affaires.

Ambassador Vasilii Nikolaevich Krupenskii, 1917. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-B2–4285-10 [P&P], Bain News Service Photograph Collection, https://www.loc.gov/item/2014705195/.

Mikhail Girs, last Russian ambassador to Italy, 1930. Bakhmeteff Archive, Columbia University, Vasilii Nikitin papers, box 1, folder: Girs, M.N. photograph.

Nabokov, born in 1871, was an uncle of the famous author Vladimir Nabokov. He had begun his civil service in the Ministry of Justice in 1894, but two years later transferred to the Foreign Ministry, where his early career was confined to the chancellery. But after participating in the peace negotiations at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 1905 that concluded the Russo-Japanese War, he began to receive postings abroad: Brussels, Washington, DC, and Calcutta. In 1916, he was appointed counselor to the Russian Embassy in London. Following Benckendorff’s death in 1917, Nabokov became chargé d’affaires.

While Nabokov was not himself without influence (particularly as the brother of the well-known Kadet politician Vladimir Nabokov), the authority of a junior diplomat could extend only so far, especially in the difficult days and years that followed the Bolshevik rise to power. He was a liberal himself, though not a Kadet, and a man of broad views, who could find points in common with former socialist Russian prime minister A...