![]()

1

What Is Defined as Real

My sons love to ask questions. When they were ages four, four and three, some of their favorite questions were about their bodies. One evening during bath time, I was tripped up by two good ones: “What’s inside my fingernail?” and “Mommy, can you take off my foot so I can see the bones inside?”

I stumbled in a different way over this one: “Mommy, what are these?”

“Testicles,” I said.

“What are testicles?”

“They are part of what makes you a boy,” I said. “All boys have testicles.” Immediately I felt disappointed with myself. “All” was a poor word choice. A boy who loses one or both testicles to accident or disease is still a boy. Some intersexual people are born with both testicles and ovaries. And in the Dominican Republic, due to a genetic issue, a number of children (called guevedoces, which means “balls at twelve”) were raised as girls, but then at puberty their testicles descended, and most (but not all) shifted to become boys.

One of my favorite quotes, taped to my office door, is, “What is defined as real is real in its effects.”[1] It may not be true that all boys have testicles, but if my sons take it as truth, there will be real consequences. Defining boyhood as strictly as I did would rule out the exceptional cases and might cause a son to question his own maleness should he lose one or both testicles.

Before I had a chance to launch into a college-level lecture from my perch on the bathroom sink, one boy announced, “Then baby boys don’t have testicles.”

Another said, “And neither do mommies or daddies or bears.”

“All” caused another problem. In their minds, because all boys have testicles, baby boys, mommies, daddies and bears are in the category of “those without testicles.” At their developmental level, they’re learning to identify males and females. They need to understand that baby boys, boys, men and daddies are all male, just as baby girls, girls, women and mommies are all female, and that animals like bears come in male and female varieties. They also need to understand that every category has complications and exceptions, but that will be a conversation for later.

I stand by my claim that testicles are part of what makes a boy a boy, but I wish I had stopped there. By claiming that all boys have testicles, I made the category too rigid and didn’t leave room for other ways of seeing boys, and for other kinds of boys. Depending on the context, “boy” could be defined genetically in terms of chromosomes (in a science class), biologically in terms of anatomy (at home in the tub) or even socially in terms of self-presentation (if a transgender girl passes as a boy, then socially she is a boy). Creating categories, even one as seemingly simple as “boy,” is not just descriptive. Categories also prescribe what is normal and right, and who belongs and who doesn’t.

Like the categories of male and female or boy and girl, human sexuality is part of culture. Sex is a gift from God, but we don’t receive it straight from heaven; it is always mediated by culture. We learn from others how to be sexy, how to find a sexual partner, and even which sexual behaviors are possible, desirable or typical. We can’t even speak about sex without culture, as language provides shared symbols that enable communication. Consider common English phrases for sexual intercourse. “Having sex” emphasizes sex as a thing that is possessed by individuals. “Doing it” portrays sex as an action performed by individuals, with “it” inferring that sex is something mundane or ordinary. “Making love” highlights intimacy and romance, and also seems to correspond with an industrial economy in which producing goods and services is valued. Taken together, contemporary ways of speaking about sex encourage people to think of sex as something an individual can have, get, make or do. More graphic euphemisms portray sex as dirty, naughty or meaningless. Language reflects the cultural meanings ascribed to sex, which shape how people express sexuality. It’s true: what is defined as real is real in its effects.

There are many cultural dimensions of human sexuality, and sexual identity is an important one. Sexual identity is a cultural pattern by which people understand their sexuality. It’s a concept that was created by people in an attempt to conceptualize human sexuality more clearly, and it has become a shared understanding that is passed on to others. In his letter to the Romans, Paul’s immediate focus was on broader issues of life in the church in Rome, but studying the sexual patterns of the world is a fitting response to his appeal in Romans 12 to cultivate reasonable or rational worship.

The Familiar Strange and the Strange Familiar

Sex seems so biological and so natural that you might assume sex works pretty much the same way for all people. But the anthropological perspective reveals that what seems “natural” may or may not be from nature. It may seem perfectly normal to eat cereal for breakfast or to sleep indoors, for example, but a crosscultural perspective would reveal that those habits are not a natural part of being human. Other people have practices that seem just as normal to them. So while it may seem perfectly natural to date before marriage, or to have sex in a bed, or to kiss in public (or to never kiss in public), none of these practices are cultural universals.

People often find that when they are immersed in a different culture, what is initially strange becomes familiar, and what was once familiar begins to seem strange. Experience in other cultures can help open our eyes to the uniqueness of what we take as “just normal” in our own world. Through long-term immersion, anthropologists try to understand the insiders’ view of other cultures. Sharyn Graham Davies, an Australian anthropologist, spent nearly two years living in South Sulawesi, a small region of Indonesia, among the Bugis ethnic group.[2] She immersed herself in the everyday lives of men, women, calalai, calabai and bissu (the five gender categories in their society) with the goal of understanding, in part, how Bugis gender roles relate to people’s sexualities.

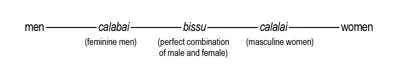

The Bugis blend of indigenous tradition and Islam, the national religion, leads them to believe that people can embody different amounts of maleness or femaleness, which allows for the possibility of more than two genders.[3] Instead of separating men and women into discrete categories, imagine a line spanning from man to woman. Calalai (masculine women) are born female but have so much male essence that they live as men in that they travel, dress as men and work in men’s professions; sometimes they are even mistaken for men. Calabai (feminine men) are born male, but their extra female essence leads them to dress and act as women, but in an over-the-top, glamorous, sexy way. They don’t feel they are women trapped in a man’s body; they feel they are calabai, feminine males. Bissu (transgender shamans) are the perfect combination of female and male elements, having come to earth from the spirit world without being divided into male or female. This is reflected in the body; many bissu are intersex, that is, born with ambiguous sexual biology. This is believed to animate their spiritual power, which is used to bless important life events like birth, marriage and death.

The overwhelming majority of Bugis people are men or women, but the notion of gender as a spectrum from male to female, and an emphasis on gender identity as shaping social roles (contrasted with our society’s focus on sexual identity), makes room for calalai, calabai or bissu to find tolerance or even acclaim in their local communities. It also shapes men’s and women’s sense of themselves as existing on a continuum, not as “opposite” sexes, or as different as Mars and Venus.

Figure 1.1. Five Bugis genders

For traditional Bugis, it would be unthinkable to be gay or lesbian. Identities based on sexual feelings are not present in their culture. Sexuality provides confirmation of gender identity (a calabai who desires women, for instance, may be suspected of being a fake), but people don’t form identities or communities around sexuality in and of itself.

Limited Imaginations

Contemporary Christian dialogue about sexuality is limited because it is framed by contemporary Western notions of sexual identity. It seems virtually impossible to find fresh ways to move forward when our imaginations are bound by the culture that shaped them. For example, Christians often become absorbed in either affirming or negating the morality of same-sex sex and related issues such as ordination of gay and lesbians and same-sex marriage. While these issues certainly are important, we must also address the underlying problem that drives these disputes. These “fixed position” debates are binary: first, framing the issue in terms of homosexuality and heterosexuality, and then asking for only affirmation or negation of same-sex sex, without more complex dialogue about human sexuality and Christian discipleship.

Because of the cultural distance, it may be easier to see how the Bugis five-gender paradigm leads to opportunities and problems that are distinctively Bugis than it is to see how our paradigms frame and direct our concerns. Imagine a child born with ambiguous genitals who grows up to display special spiritual interest and abilities. If you were Bugis, you’d identify this child as a potential bissu. If you were North American, you might never know this child as intersex because she or he would likely have had medical intervention in early childhood and be living as a girl or boy. Furthermore, if an intersex child showed special spiritual interests and abilities, the North American imagination wouldn’t connect spiritual traits with sexual physiology.

Now imagine a boy with enduring sexual feelings for other boys, but with otherwise masculine interests (no inclination to dress or act in feminine ways). If you were American, you might think he’s gay. If you were Bugis, you wouldn’t know what to make of him; there would be no category for him. The boy would likely be encouraged to marry and have children, which is necessary for full citizenship. Sexual desires that transgress marriage would have to be stifled, or indulged in violation of religious and community norms.

As far as I have read, there are no Christian theologies of Bugis sex and gender. But if there were a Bugis Christian congregation or seminary that wished to pursue these issues, believers would benefit from perceiving the socially constructed nature of calalai, calabai, bissu, and even their understanding of man and woman. Most Bugis are Muslim, and they have a variety of responses to the indigenous five-gender system. The bissu role is of central concern because it involves spirituality and religious ritual. Some Muslim Bugis reject the bissu role altogether because it is not strictly Muslim. Others see Islam as “religion” and bissu rituals as “culture,” and therefore protect the bissu role in the name of preserving Indonesian indigenous cultures. Some bissu who are also Muslim have replaced the pre-Islamic gods of their rituals with Allah. Whether or not it is explicit, these approaches acknowledge that sex and gender variations cannot be understood as solely moral dimensions of life; they are embedded in cultural beliefs, mixes of local culture with national religion, and available technologies (lack of surgeries for intersex babies, for example).

It’s almost always easier for an outsider to see the socially constructed nature of beliefs, concepts and practices; to an insider, their way of life is not just one of many possible worlds—it is just the world. It’s much more difficult for us to see how culture shapes our own beliefs and practices, but we aren’t as different from the Bugis as it may seem. Christian theology about homosexuality, for example, borrows that sexual identity category from American culture and then interprets and evaluates it with Scripture (which was written in various cultural contexts), and with Christian theology from various places and times. We might like to believe that religion and culture are as separate as meat, potatoes and vegetables on a picky child’s plate, but that’s impossible. Culture provides the words, practices, sounds, buildings, musical instruments and so on, with which we make our religious lives.

Because they configure sex and gender differently, the Bugis help me see that believing in social identities linked directly to sexual desire is just that—a belief. Cultures link sexual feelings, biology of birth, gender roles, work, dress and marital roles in various ways. Other societies, including those described in Scripture, can be both windows and mirrors: windows that offer glimpses into other ways of life, and mirrors that help us see ourselves more clearly. The Bugis conform to the pattern of their world, and U.S. Americans to the pattern of ours. The very word culture highlights the way people cohere into a functioning society with a shared language and way of life. That’s a good thing—the capacity to make culture is a God-given gift that strengthens human survival—but as believers we’re called to be discerning about the ways we participate in, carry forward and transform our cultures.

Seeing the Matrix

I warned them it was going to be postmodern. It was an upper-level anthropology seminar on sexuality in crosscultural perspective, a challenging topic at a Christian college, and the students said they were up for it. First things first: define homosexuality and heterosexuality. “We all know what we’re talking about here, right?” I teased. “So this should be easy.” Students wrote definitions on the board about attractions, feelings and behaviors, but no one seemed enthusiastic about the answers; in discussion they offered some real-life examples that didn’t seem to fit the categories. Consider a faithfully and happily married man who has occasional same-sex temptations. He calls himself heterosexual, but is he really? Or a woman who, after years of same-sex relationships, marries a man. Was she really homosexual? Is she now heterosexual?

Michael spoke up, “I’m not so sure I’m straight. Don’t get me wrong—I’m not gay, and my girlfriend hates it when I talk like this—but really, are these my only choices? I’m a whole person, with a multifaceted history and a complicated identity, and to just reduce all that to ‘gay’ or ‘straight,’ well, it just doesn’t fit me very well.” Some classmates resonated with him immediately, and one asked clarifying questions just to be sure Michael really wasn’t gay. Others expressed disappointment at how easy it was to dismantle straightness; it’s an important element of identity, and they expected it to be sturdier.

Sexual identity is extremely important to many, and people expend great effort shaping others’ perceptions of them as gay, straight, bisexual or some other designator. For example, my friend’s son, around age ten, was called “gay” because he wasn’t very competitive in sports at school. He had never been in a fight before but picked a fight with another boy just to prove he wasn’t gay. Crises of faith, identity and family emerge when people shift categories, or feel their inner experience is incongruent with the sex or gender label given to them at birth, or are unable to persuade others to see them in their desired category. But try to define “gay” or “straight,” and the words begin to slip through our fingers. Those concepts may have better described sexuality in Western societies at the time they were created (the subject of the next chapter), but using them today often feels like squeezing feet into ill-fitting shoes.

Michael told us that his sister had recently come out as a lesbian and that his Christian family was stru...