eBook - ePub

Action Research for Student Teachers

Colin Forster, Rachel Eperjesi

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Action Research for Student Teachers

Colin Forster, Rachel Eperjesi

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Action research is a popular part of many teacher training courses but understanding how to do it well is not always straightforward. Previously known as Action Research for New Teachers, this book will guide you through each step of the process, from initial stages of planning and research, through to how to analyse your data and write up your research project.

This second edition includes:

·A new 'Critical task' feature, with suggested responses

·Discussion of where action research 'fits' in the word of education research

·Exploration of the skills and attributes needed for undertaking action research

·Guidance on how to write with clarity and purpose.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Action Research for Student Teachers est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Action Research for Student Teachers par Colin Forster, Rachel Eperjesi en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Education et Teacher Training. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

1 Introduction

Objectives for this chapter

- To introduce the nature and purpose of action research as a methodology for professionals in a range of contexts to solve challenges related to their daily work

- To introduce the relevance of action research as a useful framework for new teachers to enhance and develop their practice through evidence-based evaluation

- To explore where action research fits in the world of education research

- To explore the skills and attributes needed by teachers undertaking action research

- To explain the structure of this book and how it might be used to support new and aspiring teachers undertaking an action research enquiry.

Action research

Action research is a well-established methodology that enables practitioners in a range of professional contexts to solve problems and improve their practice (Koshy, 2010). It provides a framework within which professionals can identify problems or challenges in their work, ask themselves questions about ‘how they are doing’, and seek solutions or improvements through reviewing appropriate evidence; it is the systematic analysis of a range of relevant evidence that makes action research more than just everyday evaluation. As McNiff (2016b: 9) puts it:

- Action refers to what you do.

- Research refers to how you find out about what you do.

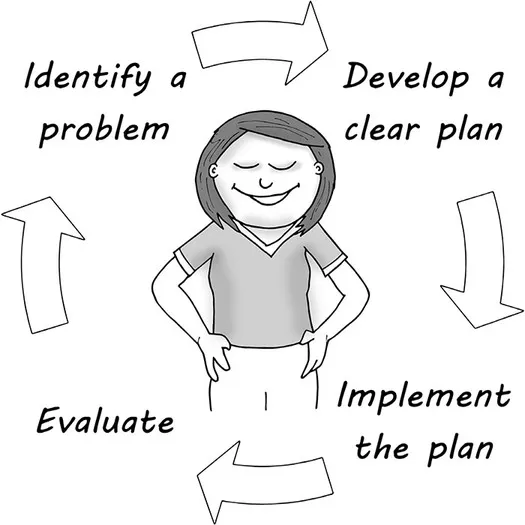

Action research is often characterised by a reflective and developmental cycle of activity, in which a practitioner identifies an aspect of their practice that they think they should develop and considers how they could find out how well they are currently doing with it. Next, they gather relevant evidence that provides some clues about the effectiveness of this particular aspect of their work and, through reflecting on this evidence, the practitioner is able to identify some specific actions they might take to ensure that they have a more significant, positive impact on outcomes related to the particular issue they are focusing on. They then put these specific actions into practice and use evidence as the basis for making judgements about the impact of the developments, for further evaluation and identification of new steps for continued improvement . . . and so the cycles go on.

Action research is particularly relevant and commonly used within the teaching profession, and has particular applicability to those who are training to be teachers and those who are at an early stage in their teaching careers.

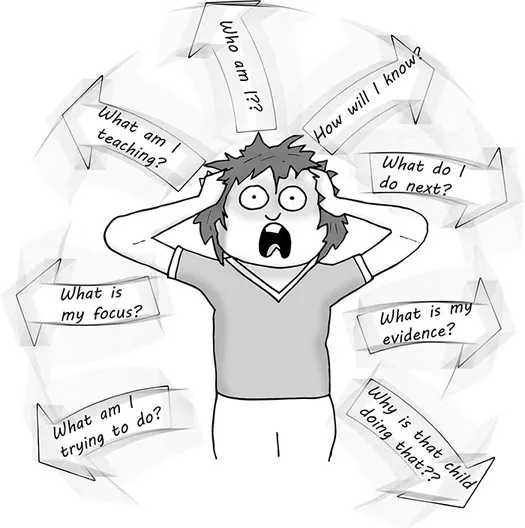

Learning to teach

Learning to teach is not an easy process. There are many new ways of thinking, ways of talking and ways of doing that need to be learnt along the way. The specific phrasing of questions, the tone of voice, the speed of speech and the use of pauses, the correct vocabulary, the order in which information should be shared, the use of technology, the organisation of teaching resources, the role of children in the classroom, the ownership of children as learners, the use of feedback (verbal, written, child-centred) on learning, the use of body language, the quality and presentation of handwriting, the modelling of expectations, the response to children and young people in distress, the celebration of successes, the confident handling of anxious or aggressive parents, and the development of the secure subject knowledge required to teach (and this is not an exhaustive list by any means): all of these need to become embedded as part of the excellent teacher’s daily practice. No wonder the old joke suggests that, with teaching, the first 40 years are the hardest.

The challenge for you, as a new or aspiring teacher, is that you will not be able to master all of these new aspects of excellent practice all at once and should focus on a small number of issues at a time, in order to embed them as part of your daily practice, all the while identifying new priorities for development and striving to master new skills.

Action research is all about improving teaching and learning with the aim of becoming an outstanding teacher. But we need to remember that, in the words of the song, ‘It ain’t what you do, it’s the way that you do it’ that gets results, so it is not about taking good practice ‘off the shelf’ and simply repeating what others have done.

Action research as evidence-based evaluation

Professor Dame Alison Peacock (quoted by the Chartered College of Teaching, n.d.) says this about the work of the Chartered College of Teaching, of which she is Chief Executive: ‘We want to support the teaching profession to thrive in an optimal, research-informed way, providing the best possible education for children and young people’. It is clear that the purpose and processes of action research align well with this ambition. In this book, we suggest that, for new and aspiring teachers, action research is best thought of as ‘evidence-based evaluation’ and as a framework for new teachers to improve their practice. All good teachers evaluate their work, but it is the detailed analysis of evidence as the basis for evaluation that makes action research such a powerful process for improving practice and only through the effective use of evidence can an action-based project be claimed to be a kind of ‘research’.

We have identified the stages in the cycles of action research in general terms, and here we identify how these stages look for new and aspiring teachers; we also outline how the stages of the process relate to the chapters in the rest of the book.

- Stage one: Identify a ‘problem’ or an aspect of your practice that needs improving. This might relate to one of the issues identified earlier in this chapter and should be a substantive aspect of your practice which, if you can improve it, will have a significant impact on outcomes for the children or young people you are teaching. In Chapter 2, we will explore, in more detail, the kinds of issues that might be considered and the sources of evidence that would help a new or aspiring teacher identify their development priorities.

- Stage two: Inform the development of your practice with knowledge. This is an often overlooked stage in the action research learning process, but it is important to be well informed about current thinking about good practice and to learn from research that has already been undertaken related to your particular focus. It is certainly better to do this reading before undertaking your project rather than afterwards. In Chapter 4, we will explore the benefits of engaging with appropriate literature and suggest some ways in which it can be done.

- Stage three: Identify the things you would need to ‘find out’ in order to make secure judgements about the effectiveness of your teaching and, in particular, its impact on learning. We will explore this in detail in Chapter 3, in which we will consider how to define clear and appropriate objectives for your study.

- Stage four: Identify the evidence that would enable you to find out what you need to know in order to improve your practice and develop a rigorous and ethical plan for gathering evidence. In Chapter 5, we will discuss the ethical considerations and practical actions that should be addressed when undertaking a school-based enquiry and, in Chapter 6, we will explore how a new or aspiring teacher might plan to gather useful and insightful evidence for their project.

- Stage five: Gather relevant evidence about your practice and analyse it to gain real and meaningful insights into the impact your teaching is having on the learning of children or young people. We will discuss, in Chapter 8, how you can ‘capture’ appropriate evidence, taking account of the busy and dynamic working environment of a school classroom and other educational settings.

- Stage six: Use the analysis of your evidence to evaluate your practice and identify ways in which it might be developed to have a more positive impact on the outcomes for the learners. In Chapter 9, we will discuss the value of this ‘real-time’ evaluation and how this can be used to understand how an individual teacher’s practice can be developed to have greater impact on learners’ progress.

- Stage seven: Implement the changes you have identified and return to stage five. Continue this reflective cycle for as long as you need to feel confident of having made good progress with the identified aspect of your teaching.

That all sounds very neat and tidy but the reality of action research is often rather ‘messy’, as it is undertaken in a dynamic context with living, breathing participants and you are a living, breathing researcher whose main challenge is to fulfil the role of the teacher, as well as undertake research. This means that the neat and tidy cycle of action research is often much more chaotic than it might appear at first.

Where action research ‘fits’ in the world of education research

There are various different approaches to research in the field of education, and it is helpful to know where action research ‘fits’ in this broad range, as this helps to define both what it is and what it is not, which we will explore further later in this chapter.

Kinds of knowledge

Different kinds of research are underpinned by different ways of thinking about how we know what we know.

Critical task 1.1

Have a look at the following questions. For each one, think about how you know what you know.

- What day is it today?

- Is smoking bad for you?

- What is money?

- How are you feeling just now?

- What shape is the Earth?

- What country are you in?

- What is learning?

Looking across all your answers, do these represent similar or different kinds of knowledge?

When talking about the nature of their research and the contribution that they hope it will make, researchers often use three key words to help them describe their own position in relation to knowledge: ‘ontology’, ‘epistemology’ and ‘paradigm’.

‘Ontology’ relates to the nature of knowledge, while ‘epistemology’ relates to how new knowledge is ‘created’. As you reflected on the questions in Critical task 1.1, you may have considered that there are different kinds of knowledge, and how it is that this knowledge has been developed: some knowledge is based on evidence, some is subjective, some is based on accepted norms and some may be highly contested. For example, we can be fairly sure that smoking is bad for us, as this claim is supported by a large body of evidence, both about the effects of smoking on the human body and the increased likelihood of suffering ill health for people who smoke. On the other hand, days of the week are not ‘real’ but based on widely accepted cultural norms: Wednesdays do not actually exist, but it can be useful for the smooth functioning of society for us all to behave as if they do.

The word ‘paradigm’ refers to the ‘world view’, or set of beliefs about knowledge, that form the basis for a particular approach to research. There are several research paradigms so, for the purposes of providing an introduction, it is helpful to compare two that are contrasting: the ‘positivist’ and ‘interpretivist’ paradigms. In the positivist paradigm, a physicist examining the behaviour of a pendulum may believe that they will be able to arrive at an answer to a particular question, if they carefully collect and analyse the relevant data. They will strengthen their confidence in the an...