![]()

Part 1

INTRODUCTION TO NURTURE GROUPS

![]()

1

Overview

This chapter describes:

- what a nurture group is

- how nurture groups help children and young people to succeed in school

- the criteria for a classic nurture group and some variants.

Nurture groups are an inclusive (Howes et al., 2002), educational, in-school resource for mainly primary school children, although increasingly aspects of the nurture approach are being used with some success in both the early years and secondary phases (Bennathan and Rose, 2008). They are for children whose emotional, social, behavioural and cognitive learning needs cannot be met in the mainstream class and who will be or should be at School Action Plus on the SEN register. Their difficulties are markedly varied, often severe, are a cause of underachievement and sometimes lead to exclusion from school. They are rarely considered appropriate for psychotherapy and are usually referred on to a resource within education such as a Pupil Referral Unit (PRU). Typically, such children have grown up in circumstances of stress and adversity sufficiently severe to limit or disturb the nurturing process of the earliest years. To varying extents, they are without the basic and essential learning that normally from birth is bound into a close and trusting relationship with an attentive and responsive parent.

School expectations

Teachers expect new entrants to school to be making progress towards meeting the Early Learning Goals (QCA, 1999) and, in their personal, social and emotional development, to:

- feel secure, trust known adults to be kind and helpful, and concerned about their well-being

- be responsive to them, biddable and cooperative

- approach and respond to other children and speak in a familiar group

- have some understanding of immediate cause and effect

- be eager to extend their past experience, and tolerate the frustration and disappointment of not succeeding

- find the school day stimulating but not overwhelming

- be confident to try new activities and initiate ideas.

This has never been the case for all children. Disquiet, which became more evident in the 1960s, continues into the 21st century. As the gap widens and is perceived more generally to be a barrier to learning, there is recognition at government level of the need to intervene. The Steer report on behaviour in schools, Learning Behaviour: Lessons Learned (DCSF, 2009a), considers nurture groups to be an important resource for improving children’s behaviour. They have a clear rationale underpinned by sound theory but are easily accessible to practitioners and are cost-effective.

Evaluations from some LAs and individual schools demonstrate that nurture groups are proving to be more economically sustainable than other support provided for vulnerable children. One LA, LB Enfield, has identified the following costings (2009) for children in various support programmes (all figures are approximate):

| Complex needs placement in an Enfield school for an Enfield child (middle band C) | £13,000+ per annum |

| Out-of-borough day school for one child (band E) | £17,000+ per annum |

| EBD out-of-borough residential placement for one child (independent school) | £40,000+ per annum |

| Full-time LSA support per child | £14,000+ per annum |

| Nurture group provision (for a minimum of 10 children) | £55,000 per annum |

| Nurture group provision (for one child) | £5,500 per annum |

| An established, classic nurture group may have up to 30 children passing through each year, i.e. a regular primary class group size which brings the cost down to £1,833 per child. |

The aim of the nurture group is to create the world of earliest childhood in school, and through this build in the basic and essential learning experiences normally gained in the first three years of life, thus enabling the children to participate fully in the mainstream class, typically within a year. The process is modelled on normal development from birth and the content is the essential precursor of the statutory National Curriculum including the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) (DCSF, 2008a).

Children’s difficulties: their nature and origin

Children’s difficulties in school are often severe, and sometimes seem bizarre. They range from autistic-like behaviour at one extreme, to disruptive behaviour at the other that may involve physical violence and sometimes exclusion from school. Although not always immediately apparent, many of the children have not reached the developmental level of the normal three-year-old, and are in difficulties from the time they enter school. They undermine the teachers’ skills and cause enormous stress and despair, and sometimes negativism. They are not usually felt to be suitable for psychotherapy because to varying extents all aspects of their development have been impaired: their experience is limited, poorly organized and has little coherence, their concepts are imperfect and their feelings confused. They are without a sufficiently organized and coherent past experience from which to develop and there is no clear focus for intervention.

The parents, too, are often difficult to engage. Many of them live under extreme and disabling personal stress. If referred to a mental health resource because of their children’s difficulties in school, they have the burden of finding their way to an unfamiliar place to face a bewildering discussion and the visit can be counterproductive. Many first appointments are not kept, and if kept are rarely sustained. The aims of Sure Start and the move to children’s centres are welcome but have yet to reach the most disadvantaged. For too many families, it all seems of little relevance, particularly when their situation seems beyond repair; feelings are too chaotic to disentangle, or are submerged under anger or depression.

The children’s difficulties seem related to the stage in the earliest years when nurturing care was critically impaired. Over the years, changing historical forces have led to a different distribution of the more clearly defined difficulties; those that are more generalized have increased markedly and over a wider social spectrum.

Children referred to nurture groups fall broadly into two groups, and Chapter 10 has detailed descriptions.

Nurture children

These are reception-age children who are functionally below the age of three, or, if older, at least two to three years below their chronological age; they all have considerable social, emotional, behavioural and learning difficulties. These were relatively clearly defined in the 1960s in the area where nurture groups were originally developed, and it is from this experience that the thinking and practice of the nurture groups derive.

Children who need nurturing

These children are also successfully placed in nurture groups but are not nurture children. They are emotionally disorganized, but are not without the basic learning of the earliest years. Other forms of provision for children with SEBD may meet some of their needs although they often continue to underachieve. Teachers may respond intuitively to their underlying need for attachment and provide domestic experiences and family-type relationships but these are not necessarily part of the planned intervention.

Multiple and varied difficulties but shared needs

The difficulties of almost all children in nurture groups are multiple, and a disproportionate number, compared with the general school population, have complicating features such as motor coordination and speech and language difficulties, impaired hearing or sight, or ill health.

Importantly, the teacher works with an assistant within this complexity, without needing to understand how these complex and varied difficulties came about. They rarely need to know the nature of the past stress on the children, and attempting to understand the dynamics of the particular family and the children’s perception of themselves and their world is neither feasible nor relevant. The children share a history of early developmental impairment and loss; their common need is for restorative learning experiences at an earlier developmental level.

The basis of nurture work: the teacher’s primary task

Nurture work is based on the observation that everyone developmentally ahead of young children seems biologically programmed into relating to them in a developmentally appropriate way. This is the intuitive response that the practitioners bring to their work.

Both adults work together in partnership, using their particular expertise to relate intuitively and appropriately to the children’s attachment needs, drawing on an understanding of child development, using observational and assessment skills and having detailed curriculum subject knowledge from the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) through to the age-appropriate National Curriculum levels.

The model

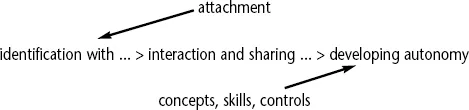

The model is the attentive, interactive process of parents and children in the earliest years within a structure commensurate with the physical and physiological development of babies and toddlers. It focuses and expands on the relational features from recognized child development phases such as those provided in the EYFS materials (DCSF, 2008a). The nurture group model is shown below.

Earliest learning: a summary chart

Figure 1. Early Nurture

Table 1. The Context of Early Childhood Experiences

| Babies/young children in the home | Re-created structures in the nurture group |

| Babies are emotionally and physically attached from the beginning, are physically dependent and need protection | Close physical proximity in the home area in a domestic setting facilitates emotional and physical attachment. |

| Experiences are determined by their developmental level (mobility, vision, interest, attention), and parents’ intuitive response to their needs. | T/A (teacher and/or assistant) select basic experiences, and control them. They emphasize developmentally relevant features and direct the children’s attention to these. |

| The waking day is short, slow-moving, broken up by rest and routines. There is a clear time structure. Physical needs determine the rhythm of the day. | The day is broken up by slow-moving interludes and routines. Everything is taken slowly, and there is a clear time structure. |

| Parents provide simple, restricted, repetitive routines and consistent management from the beginning and manageable learning experiences through appropriate play materials and developmentally relevant interaction. | T/A establish routines, emphasize order and routine; ensure much repetition; achieve/convey behavioural expectations by clear prohibitions and limits. Toys and activities are developmentally relevant, and the adults’ language and interaction are appropriate for this level. |

The situation is made appropriate for an earlier developmental level; it is simpler, more immediate, more routinized, more protected. Restrictions and constraints provide clarity of experience and focus the children’s attention; they engage at this level, attention is held and there is much repetition. Basic experiences and attachment to the adults are consolidated. Children experience satisfaction and approval, and attachment to the adults is strengthened. Routine gives security and they anticipate with confidence and pleasure.

Growth-promoting patterns are established.

Table 2. The Content of Early Childhood Experiences

This stage relates to the developmental phase from birth to approximately 11 months.

| Attachment and proximity: earliest learning |

| Babies/young children in the home | Re-created structures in the nurture group |

| Food, comfort, holding close; consistent care and support. | Food, comfort, close physical contact; consistent care and support. |

| Cradling, rocking; sensory exploration; touch in communication. | Cradling, rocking; sensory exploration; touch in communication. |

| Intense concentration on parents’eyes and face. They communicate mood/feelings through face/voice, spontaneously exaggerating their response. | T/A draw children’s attention to their eyes and faces, and make and establish eye contact. They deliberately exaggerate their facial expression and tone of voice. |

| Closeness; intimate interplay; shared feelings/satisfaction Parents’ verbal accompaniment reflects pleasure, and child’s loveableness and value. Parents give frequent positive acknowledgement of their child. | There is closeness, intimate interplay and shared feelings/satisfaction. T/A’s verbal accompaniment reflects pleasure, and child’s loveableness and value. They make frequent positive acknowledgement of each child. |

| Parents have age-a... |