![]()

![]()

Any “economics of …” first requires an understanding of the topic in question. This first chapter deals with the nature of health and disease, and the complex medical institutions and systems that modern societies have put in place to prevent, diagnose and treat illness. We give a short, introductory overview of health and disease and equity of healthcare. This chapter (as well as Chapters 2 and 5) are primarily descriptive. They do not provide theory (e.g. how to improve “efficiency”); this will be covered in later parts of the book.

1.1 Definitions and models of “health” and “disease”

“Health” is a constitutive human experience. It is not by chance that since antiquity (and historical records began) every society has had health experts (as opposed to economists). Medicine was one of the founding faculties of the oldest European universities – in addition to theology, philosophy and law. At first glance, “health” appears both easy to define as well as being an issue of pure natural science; after all, diseases (and health) are about biology. However, on closer examination, things are much more complicated. “Health” interacts with physiology but also affects psychology, sociology, politics and ethics, amongst others, and vice versa: for example, the concept of “pain” is not just an issue of pure biology since in some societies patients are entitled to complain about it whereas in others they are expected to be brave. The health of a population also heavily influences its economic power (the Covid-19 pandemic is a case in point).

This is one of the reasons why it is notoriously difficult to succinctly define “health” and “illness”. The key challenges are:

•Is health a state/stock (of being healthy) or a process/flow (of producing health)? Is health something that individuals and society experience or constantly “create” by, for example, fighting pathogens?

•Is health something to be felt (feeling ill) or something that enables people to perform (being able to work)?

•Who decides whether a patient is ill – the patient or society? The decision can be based on individual perception or societal definition (declaring someone ill, for example, to allow them to access sick pay).

•Is health, as well as disease, a medical fact and/or a psychological and social issue? For example, women’s life expectancy is three years longer than that of men in Sweden but 11 years longer in Russia. It is unlikely that this difference is due only to biological (e.g. genetic) reasons.

Take the following example. Roger, a civil servant at a property registry office, has broken his left elbow. He is on sick leave for four weeks. Sitting at home is boring, so he visits his colleagues daily. However, they are already irked by this situation; they think that Roger could do some work, for example talk to visitors, not least because they have a hard time taking on his job in addition to their own duties. Roger does not understand this attitude; his doctor told him that he should nurse his arm. Is Roger healthy, or not?

Might it be possible to evade the problem of definition of “health” by focusing on the definition of “disease”? Health and disease do mirror each other. Without disease, there is no health and vice versa. A famous definition of health opens the preamble of the constitution of the 1946 World Health Organization: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” Note that, in this case, health is a state (and not a process). There are plenty of other definitions. Sociologist Talcott Parsons, for example, stressed the point that ill health impairs our ability to perform our roles in society. In this understanding, society (not the patient herself) is key in defining health. It is not possible to reconcile the differences between the different types of definition. Health and disease are both medical facts and, at the same time, psychologically and socially mediated. This is important to understand since it explains why social organizations contribute to our understanding of sickness: if medicine was pure natural science, there is no reason why an association of employers, the church or a union should be involved in deciding rules for defining sick leave or specific treatment pathways, for example.

Finally, this means that medicine is not the only science involved with health and disease. Sociology may detect important insights into the way medicine is practised. Economics yields insights into financing or decision making. History provides information about earlier institutions related to treatment, for example.

In addition to definitions of disease, there are also models of disease. There are many different models of “health” as well as models of “disease” in many different disciplines, such as public health, nursing and health economics.

The “biomedical model” is often cited in non-medical literature. Its focus is on the physical processes of disease (for example, its pathology, biochemistry and physiology) and it does not take psychosocial issues into account. Some scholars consider this to be the leading model in western medicine. A more encompassing approach is taken with the biopsychosocial model, which looks at the mutual relationship between biology, psychology and socio-environmental factors and examines how these aspects play a role in health and disease models.

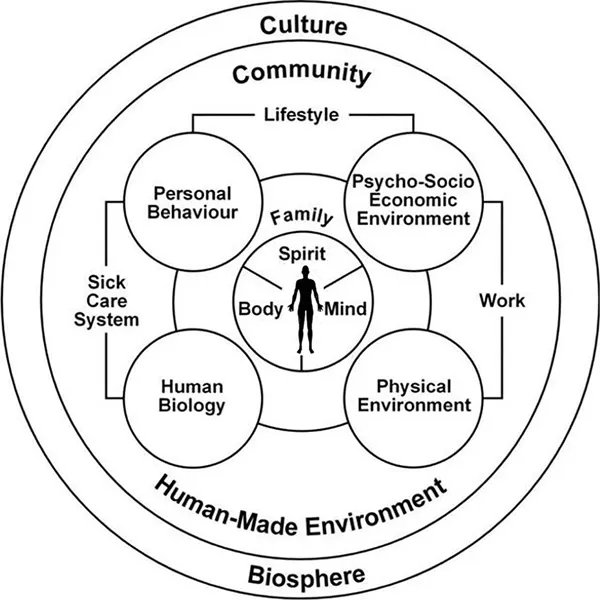

Many models use an illustration to describe health. Figure 1.1 shows the Mandala of Health (named after the appearance of the model, which looks like a mandala, the figurative and geometric picture in the Hindu and Buddhist religions), mapping out factors influencing health such as culture, environment, the family and so on.

Another highly influential model is Anton Antonovsky’s concept of salutogenesis. The basic question addressed by Antonovksy, a medical sociologist, concerned how some people manage to cope with extreme stress (such as concentration camp survivors). He basically inverted the question “What makes you sick?” and asked “What makes you healthy?” This approach has contributed to current research in resilience. It is sometimes posited as a counter-model to medicine and its idea of pathology. In our view, it is a complementary approach because the key point is that resilience is disease-specific. We will come back to this issue after discussing specific diseases (rather than “disease” as such).

1.2 Pathology and the definition of specific diseases

Medicine engages little in the discussion of definitions of health and disease. Doctors are trained to deal with specific diseases (e.g. tuberculosis); “disease” does not mean much to them. The same holds true for patients: they want their specific disease to be cured – not to have a debate about “health”.

Note that many problems of the discussion of “health” disappear when talking about specific diseases. For example, it is relatively easy to examine social factors in lung cancer (such as smoking habits) or in Type II diabetes (nutrition, physical activity, etc.). When discussing disease in general, the relationship between social factors and disease is somewhat unspecific.

Since it is so important to study specific diseases, we need to ask: What is a single disease? Once aetiology (cause) and pathogenesis (course) are investigated, a disease is defined. For example, tuberculosis is caused by tubercle bacteria, which create inflammation at several locations, generating functional loss. As noted earlier, social psychology and economics greatly modify pathogenesis. In the case of lung cancer, its aetiology is not yet fully known but its pathogenesis is.

The ability to diagnose specific diseases marks the difference between modern and earlier medicine. Note that it is difficult to achieve scientific progress if different things are constantly intermingled (e.g. by focusing on a symptom rather than a disease). For example, there is little insight to be gained from studying “red skin spots” because this may be acne, neurodermitis, some inflammation and so on. Therefore, patients with red spots will behave quite differently, creating an irresolvable puzzle for the scientist. It does make sense to study “tuberculosis”. That is, once you manage to study the right thing (a specific disease rather than a mixture of diseases) you will learn more about it more quickly.

This is why diagnosis is the core concept of modern medicine: medicine “thinks in diagnoses”. Note that this is an important point for understanding the miscommunication between doctors and economists: medics think in diagnoses, economists (often) in input/output. For example, when discussing the need for a new MRI scanner, physicians will think about which patients and what diseases they can better diagnose; hospital managers, in contrast, will be more concerned with costs, financing and potential additional reimbursement.

Diseases can be described as a matrix, as shown in Table 1.1. In order to specifically describe how social psychology influences the course of a disease, we need to study a specific disease. For example, dry and warm housing kills tubercle bacteria (but does not impact smoking). Recommendations that are aimed at preventing disease in general will remain at the level of “eat more fruit”. While this is correct, we also want specific knowledge for specific diseases. The same is true for salutogenesis: “resilience” is a rather vague concept. Resilience in the case of...