![]()

PROPOSITION 1

History Is Not One Damn Thing after Another

SUMMARY

A first step in finding a politic which is “neither right nor left nor religious” is construing history correctly. For some, “history is just one damn thing after another.” This famed phrase well depicts those who believe history has no meaning, no direction or goal, no ultimate purpose.

Many Christians also think this: “It’s all going to burn, and none of this matters.” What matters, they say, is the human soul “going to heaven when we die.” No need to concern ourselves with troubling social or political matters because “God’s got this.” Politics and social affairs are of no concern to the faithful.

Many Jews, Muslims, and Christians know better. Some prominent early Christians, in fact, believed such spiritualizing to be a grave heresy that would destroy the Christian faith. They saw human history as the stage for the unfolding of the drama of God’s work. In this drama God was assured to be the victor, even if God’s ways are often inscrutable, even exasperating to those who love God. This God who had created a good creation would restore it, redeem it, save it. This God would set right the injustice and violence, remove the arrogant mighty ones from their throne rooms and White Houses, fill up the hungry, and bind up the oppressed.

In this drama some humans, feeble and petty as they may be, ally themselves for the work of God. Meanwhile, many of the preening, arrogant powers array themselves against both God and humankind. Those arrogant powers often serve as the handmaidens of death, while the God of life keeps intruding, or so it appears to the powers, bringing light into the darkness.

But human history is not one damn meaningless thing after another, even if the horror of the mundane evil propagated by the powers tempts us to despair. History has a goal, a direction toward a climax: the author of life shall write a tale, has written a tale, in which all lies and greed and ugliness and war; prisons and lusts, oppression and hate; hostility, disease, contempt, and envy; all shall be undone and set right, and there shall come a triumph of truth and goodness and beauty, which no ear has yet heard, and no eye has yet seen.

EXPOSITION

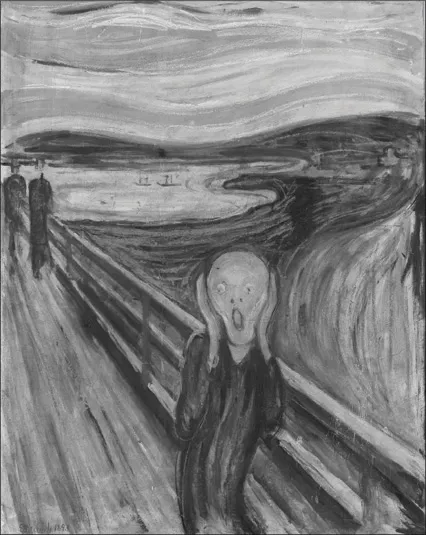

The Scream has been called the Mona Lisa of the twentieth century. Edvard Munch’s iconic painting arose from a dreadful vision he had one day at sunset. Walking along a fjord in his native Norway, he said he “sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.” That scream captures the modern sense of despair, in which no hope remains, only anxiety, loneliness, and despondency.

Munch’s artistic angst illustrates well some common philosophical convictions about history: that history has no direction or is merely an endless cycle of repetition or is but one damn meaningless thing after another. There are also religions, supposedly Christian versions of such, that think that human history is ultimately unimportant. These alleged Christian versions postulate some hope, some purpose, but it is a purpose beyond history, outside of history. It is a reward “up there,” souls floating off to heaven. “Our true home,” they say, “is in heaven. We need not concern ourselves with social or political or historical matters.” One therapeutic solution to Munch’s Scream is simply not to look too closely at history, not get ourselves involved in matters that don’t concern us in our spiritual contentment. If you don’t pay attention to the death camps or the brokenness of the cities or the systemic greed undergirding our economies, then you need not feel the despair. You simply ignore it, look beyond, to the sweet by-and-by.

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893, oil, tempera, and pastel on cardboard, 91 x 73 cm, National Gallery of Norway. Wikimedia Commons

This is Marx’s classical critique: religion as the opiate of the masses.

But as much biblical scholarship has been contending of late, “going to heaven” is not the point of the New Testament, nor did early Christians believe it so.

Along with recent biblical scholarship, the poets and prophets and song-singers have always known better. The Hebrew prophets envisioned a day in which “the lamb shall lie down with the lion,” “the nations shall learn war no more,” and “swords shall be beaten into plowshares.” The poets and lyricists of our own day insist that “a change is gonna come” and that we “still haven’t found what [we’re] looking for.” And Martin Luther King Jr. proclaimed that he had a dream and that “the arc of history is long, but it bends toward justice.”

All these poetic utterances point us toward hopefulness. Each assumes that history is not, in the final analysis, a meaningless morass of vanity. Instead, history has a direction: injustice undone, brokenness bound up, captivity taken captive. This is the goal of history, the end of history. We need not confuse “end of history” with the termination of time; it is, rather, best considered as the final goal toward which all things are moving.1

Historic Christianity insists precisely this: that history is headed toward a glorious re-creation the likes of which only poets can begin to voice.

This conviction is a most significant starting point for considering a sociopolitical vision for Christian practice.

Hope as an Interpretation of History

This idea—a goal of history—entails the notion of hope.

This is where the American myth and Christian teaching have a high degree of overlap: both assert the notion of a direction to history and thus the practical importance of hope. There is similar overlap with the secularist who speaks of progress, assuming some direction in human history.2 As the philosopher John Gray describes John Stuart Mill, one of the preeminent philosophers of the liberal tradition in the West: “he founded an orthodoxy—the belief in improvement that is the unthinking faith of people who think they have no religion.”3

If it is true that Christianity does proclaim that history matters and is going somewhere, then it turns out that many American and secularist forms of hope are more Christian than the otherworldly dreams of some Christians. Or, at a minimum, we can say that such Americans and secularists are more Christian in their conviction regarding the immeasurable worth of the whole of human history.

When Americans and secularists insist that history matters—that social policy and scientific concern for the earth matter, that economic policy and staggering disparities in wealth matter, that the industrialization of war and imprisonment for profit matter—they show themselves, in this regard, more Christian than many Christians.

The hope of heaven, in other words, too easily becomes an ahistorical hope, a hope that cares nothing for the unfolding of the human drama, except perhaps to hope that sufficient religious or moral choices are rightly made so that the soul can sweep through the Pearly Gates.

In this way, some American revivalists may have done more to undermine Christianity in America than the secularists by making the locus of Christianity the individual’s judgment before the throne of God, a religion that has little to say to the teeming and throbbing pain of human history and instead calls us to cast our vision to an afterlife removed from care for human history or for God’s good creation. Such a tendency contributed to Malcolm X renouncing Christianity and embracing Islam. “The white man has taught us to shout and sing and pray until we die, to wait until death, for some dreamy heaven-in-the-hereafter, when we’re dead, while this white man has milk and honey in the streets paved with golden dollars right here on this earth!”4

One of the failings of the secularist notion of progress is its vague lack of content: What does progress entail? What does it look like? What is its content?

Similarly, the Christian notion of hope must attend to these same questions. The biblical creation account, in which Jews and Christians maintain that the creation itself is good, is indispensable in beginning to answer such questions. The Genesis account about creation is not a sort of crypto-scientific description best read as a literal account of the unfolding of the cosmos. Instead, the Genesis account insists on the moral and aesthetic goodness of the creation grounded and rooted in the abundant generosity of God. It presumes a community inherent in the very nature of God and that this self-giving God invited all creation, and humankind in a special way, to participate in the joyous work of tilling and cultivating in the unfolding story of the garden of God.

And yet death and death’s handmaidens duped the humans, vandalizing the abode of God and humankind. And yet more, this God who is good and patient and long-suffering did not leave humankind to its own devices but would act in love and power and justice to set things right—while still honoring humankind’s radical freedom to reject the good ways of God—to free humankind from the bondage in which it found itself.

“New heavens and new earth”—that’s what one of the prophets called the greatly anticipated redemption of God. Christianity was not concerned first and foremost with some realm of disembodied spirits beyond the pale of human history.

Consider the stunning objection of one of the early church martyrs, Justin. He was arrested and beheaded for his faith. His commentary is striking. There are some “who are called Christians,” he said rather derisively, who insisted that “their souls, when they die, are taken to heaven.” He classified such people among “godless, impious heretics.”5

This is an ironic, odd reality: that an early defender of Christianity who refused to submit to the demands of the Roman Empire, who insisted that Jesus was Lord, and who was executed for his stance, would say that our American Joe Christian is not in fact a Christian but a heretic. Justin was not executed because he was religious. He was executed because he held to a competing interpretation of human history. Justin held to an alternative politic that entailed that the Word of God revealed in this Jesus of Nazareth was the only rational explanation that made sense of our lives and was the only rational ground for hope. The resurrecting power of God which had raised this Jesus from the dead would not only raise all of us but also make new the heavens and the earth and set all things right.

Jesus and other early Christians were not executed because they were spiritual. They were executed because their politic was a threat to the powers that be.

The Content of the Hope

It is not the afterlife for which the prophet longs but the setting right of this life: the pain of lost loves and the death of infants, of old griefs and deep regret, of the weeping of mothers or the cries of war. All shall be wrought up into the work of this God who shall wipe away every tear from every eye and make all things right.

Hear, for example, the Hebrew prophet Isaiah:

For I am about to create new heavens

and a new earth;

the former things shall not be remembered

or come to min...