- 260 pages

- French

- ePUB (adaptée aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

À propos de ce livre

What is heritage?? This is the most fundamental but difficult question to be answered in heritage studies. It has been addressed many times, but singular definitions always seem to come up short. This book contributes to understandings of heritage as a multifarious construct. It sees it not as something defined by material objects, but as a cultural, economic, and political resource, a discursive practice, and as a process or performative act that engages with the past, present, and future. Notions of Heritage explores the challenges and consequences that result from overlapping, outdated understandings of heritage, as well as new notions of heritage altogether, whether in form or in practice, paving the way forward in the field of critical heritage studies.

Qu'est-ce que le patrimoine?? C'est une question à la fois fondamentale et complexe à laquelle cherchent à répondre les études sur le patrimoine. Celle-ci a été maintes fois abordée, mais les définitions précises semblent toujours manquer. Cet ouvrage contribue à la compréhension du patrimoine comme construction multiforme. Il ne le considère pas en tant qu'objets matériels, mais comme une ressource culturelle, économique et politique, une pratique discursive, et en tant que processus ou acte performatif qui s'engage avec le passé, le présent et le futur. Notions de patrimoine explore les défis et les conséquences qui résultent des conceptions obsolètes et chevauchantes du patrimoine ainsi que les nouvelles notions du patrimoine, que ce soit dans la forme ou dans la pratique, qui ouvrent la voie aux études critiques sur le sujet.

Jessica Mace, Ph.D., is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Art History at the University of Toronto and Adjunct Professor in the Department of Urban and Tourism Studies at the Université du Québec à Montréal.

Yujie Zhu, Ph.D., is a Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Heritage and Museum Studies of the Australian National University.

With contributions from Patrick Bailey, Adélie De Marre, Myriam Guillemette, Rebecca Hingley, Myriam Joannette, Jessica Mace, Ainslee Meredith, Magdalena Novoa E., Wenzhuo Zhang, Hao Zheng and Yujie Zhu.

Foire aux questions

Oui, vous pouvez résilier à tout moment à partir de l'onglet Abonnement dans les paramètres de votre compte sur le site Web de Perlego. Votre abonnement restera actif jusqu'à la fin de votre période de facturation actuelle. Découvrez comment résilier votre abonnement.

Non, les livres ne peuvent pas être téléchargés sous forme de fichiers externes, tels que des PDF, pour être utilisés en dehors de Perlego. Cependant, vous pouvez télécharger des livres dans l'application Perlego pour les lire hors ligne sur votre téléphone portable ou votre tablette. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Perlego propose deux abonnements : Essentiel et Complet

- Essentiel est idéal pour les étudiants et les professionnels qui aiment explorer un large éventail de sujets. Accédez à la bibliothèque Essentiel comprenant plus de 800 000 titres de référence et best-sellers dans les domaines du commerce, du développement personnel et des sciences humaines. Il comprend un temps de lecture illimité et la voix standard de la fonction Écouter.

- Complet est parfait pour les étudiants avancés et les chercheurs qui ont besoin d'un accès complet et illimité. Accédez à plus de 1,4 million de livres sur des centaines de sujets, y compris des titres académiques et spécialisés. L'abonnement Complet comprend également des fonctionnalités avancées telles que la fonction Écouter Premium et l'Assistant de recherche.

Nous sommes un service d'abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d'un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d'un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu'il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l'écouter. L'outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l'accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Oui ! Vous pouvez utiliser l'application Perlego sur les appareils iOS ou Android pour lire à tout moment, n'importe où, même hors ligne. Parfait pour les trajets quotidiens ou lorsque vous êtes en déplacement.

Veuillez noter que nous ne pouvons pas prendre en charge les appareils fonctionnant sur iOS 13 et Android 7 ou versions antérieures. En savoir plus sur l'utilisation de l'application.

Veuillez noter que nous ne pouvons pas prendre en charge les appareils fonctionnant sur iOS 13 et Android 7 ou versions antérieures. En savoir plus sur l'utilisation de l'application.

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Notions of Heritage par Jessica Mace,Yujie Zhu en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu'à d'autres livres populaires dans Architecture et Architecture générale. Nous disposons de plus d'un million d'ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

Architecture

Heritage as discourse

Le patrimoine comme discours

Antarctic historic sites and monuments

Conceptualizing heritage on and around the frozen continent

Rebecca Hingley

Heritage frozen in time

The notion of Antarctic heritage may seem peculiar considering that humans have only relatively recently begun to interact with this polar space, and given that no Indigenous population ever permanently inhabited the region. Nevertheless, historic remains have been found and protected on and around the continent. Although the concept of heritage is not actively contested in this part of the world, it has the potential to be as multiple actors in the region engage with it, express divergent perceptions of it, and therefore could pose competing management approaches for it. The primary objective of this chapter is to dissect the concept of heritage in Antarctica by dismantling the official discourse that defines and manages historic remains in the region at present, and identifying the authors of the discourse as well as what it constitutes. This first section provides a brief history of cultural heritage management in the region ; the second section identifies who is responsible for the construction of the official discourse ; the third section unpacks how this official discourse conceptualizes heritage ; the fourth section considers the challenges the official discourse faces ; and the fifth and final section summarizes the unexceptional nature of the official discourse and what this might mean for future management.

A photograph of Mawson’s Huts (Figure 1.1) at Cape Denison in Antarctica depicts the epitome and dominant conceptualization of Antarctic heritage ; a scene of expeditions past with artefacts left in their place and frozen in time. They provide the perfect backdrop for romantic tales of human endeavour, resilience, and survival. In this case, the huts marked the end of a gruelling journey in 1913 for the Australian Antarctic explorer Sir Douglas Mawson, in which he witnessed the death of both of his companions, battled starvation and exhaustion due to the loss of precious provisions, and endured debilitating injuries for tens of kilometres.1

FIGURE 1.1

Mawson’s Huts at Commonwealth Bay, East Antarctica

Source : Geoff Ashley, 1997 (for the Mawson’s Huts Foundation).

But not all historic remains in the Antarctic region commemorate such “heroic” events, are as well preserved, or are even officially recognized as heritage. A register for historic resources in the region was created in 1972 by Antarctic states to determine and protect sites of recognized “historic value.”2 There are currently 94 entries on this legally-binding register (the HSM List), 89 of which are protected under active measures. There are several expedition huts on the register like Mawson’s dating from the “Heroic Era” of Antarctic exploration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, there are also broken-down tractors, fallen or falling down flag masts, decommissioned nuclear power reactors, and other less appealing material remains of past human activity in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean. As humans have only encountered Antarctica within the past 200 years — with the first recorded sighting of the continent in 18203 — states with HSMs could potentially be suspected of forging national Antarctic heritages in an attempt to demonstrate to their peers the past, as well as intended future, occupation of the “last frontier.” The Antarctic heritage framework therefore not only dictates what heritage in Antarctica is and how it should be managed, it also establishes and to some extent validates national presence in this polar region. The framework itself is comprised of a list, guidelines, and guide ; three living documents that play differing yet complementary roles in the conceptualization and management of heritage in Antarctica, and that have evolved to varying degrees over the past six decades.

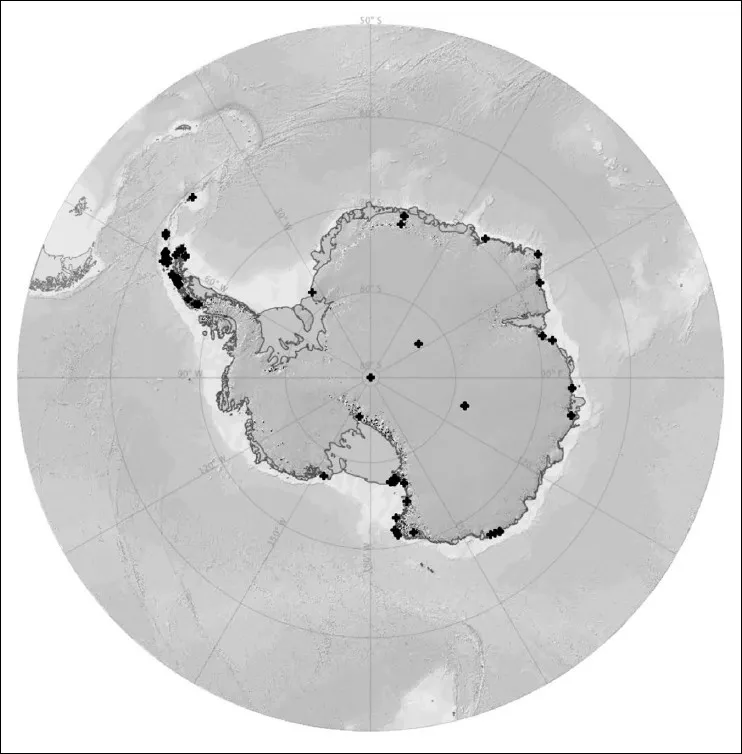

Typology, features, and distribution of the cultural heritage that this framework represents provide context for the broader discourse analysis within this chapter. A typology of HSMs was first offered by Patricia Warren in 1989 that delineated eight categories on which states base an HSM proposal : to commemorate the Heroic Era, an expedition, the deceased, a station, scientific work, a national hero, a head of state visit, or no identifiable reason.4 Warren’s thesis was the first academic attempt to “fill a gap in the existing system for designating and protecting the Historic Monuments of the Antarctic,”5 and her categories still stand today. With regard to the physical features of the HSM themselves, Ricardo Roura suggests that buildings, camps, and human remains are the “things” most commonly designated as HSMs in his geopolitical survey of the List in 2016.6 In this study he also found that the primary function of HSMs is site occupation, as this can effectively provide a state with a timestamp for their presence on the continent.7 Lastly, the geospatial distribution of HSMs across the continent is not uniform — as indicated in Figure 1.2 by the concentration of crosses that represent HSMs on the peninsula.

FIGURE 1.2

Distribution of HSMs in Antarctica

Source : Antarctic Digital Database, 2019.

Considering that many of the Antarctic expeditions of the Heroic Era departed from South America due to its proximity, and therefore made first point of contact with the peninsula, this “hot spot” of historical activity is to be expected. This places a significant concentration of HSMs in the overlapping territories of Argentina, Chile, and the United Kingdom (UK), sometimes resulting in one state’s HSM being situated in another’s claimed territory according to contemporary cartography. With these trends and characteristics in mind, the next section identifies whose perspective has been codified in the framework that legitimizes heritage in this part of the world.

Whose perspective counts ?

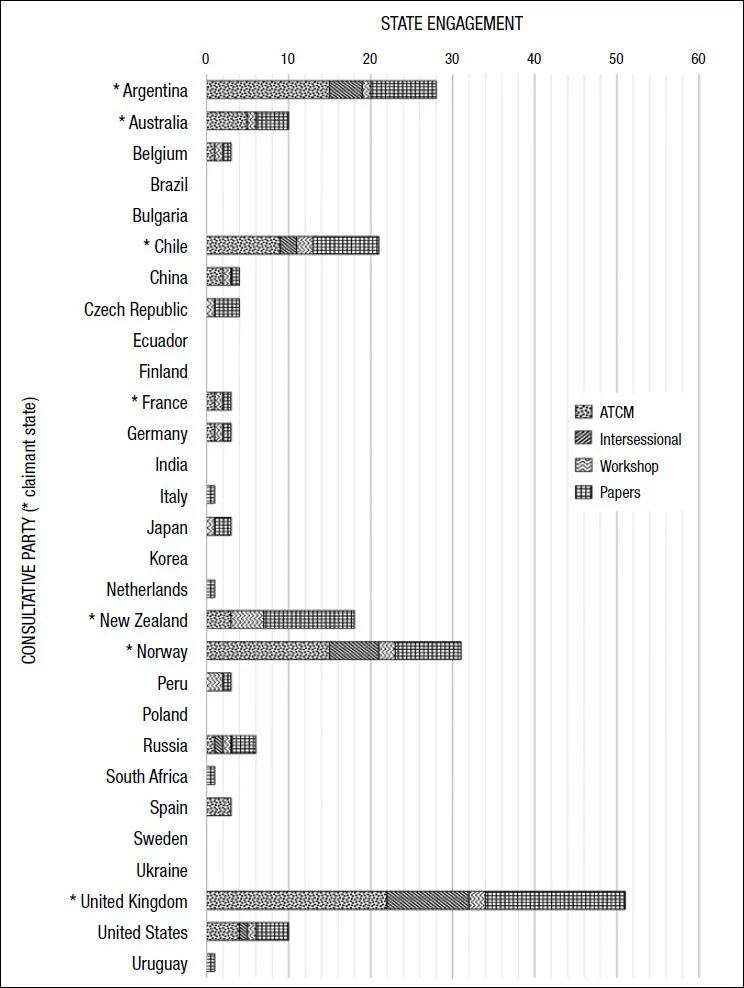

What one person considers or conceives of as heritage, another may not ; therefore, how does this incongruity play out in the Antarctic context, or more pertinently, who are the authors of discourse on Antarctic heritage ? Fifty-four states, who account for a majority of the world’s population, have acceded to the Treaty.8 But given the power dynamics present within the ATS — detailed further below — a hierarchy of heritage was suspected. In order to discern whose perspective was, and is, being privileged over others, a discourse analysis was undertaken. This analysis included the coding of official papers, statements, and reports within the regime that governs Antarctic heritage (the ATS) ; and identifying the parties who wrote them, submitted them, or supported their claims. Although the limitations of this quantitative reading are appreciated, such an interpretation does produce a valuable overview of which states’ perspectives are being formally recorded and translated into international law more often than others. This enshrinement within international law is what makes this perspective count. The legislation of this perspective is particularly important given that continued peace within the region relies on the states’ steadfast commitment to the multilateral institutions that govern it. Of the 54 Antarctic states : 29 are consultative parties authorized to partake in decision making ; 12 of these are original signatories, who have been present since the Treaty was signed in 1959 ; and 7 are claimant states9 — that is, states that made a formal claim to a territory in Antarctica prior to the Antarctic Treaty’s freezing of these claims. The Treaty neither supports nor denies these claims, but stipulates that they must not be acted upon while it is in force.10 Therefore, due to their high level of investment in the region’s geopolitics, it was expected that the claimant states would be much more active in the development of the Antarctic heritage framework than the non-claimant states, as confirmed in Figure 1.3.

FIGURE 1.3

Preliminary findings of state engagement in Antarctic heritage management

Note : The dots represent the number of times a state raised or responded to a heritage-related matter at an Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM) ; the diagonal lines represent the number of times a state participated in intersessional discussions on heritage ; the wavy lines represent the number of times a state participated in a workshop on heritage ; and the grid represents the number of heritage-related papers a state submitted to an ATCM.

As an aside, non-state actor...

Table des matières

- Couverture

- Page de titre

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments | Remerciements

- List of figures and tables | Liste des figures et tableaux

- List of abbreviations and acronyms | Liste des sigles et acronymes

- Introduction: Notions of heritage

- Part | Partie 1: Heritage as discourse: Le patrimoine comme discours

- Part | Partie 2: Heritage as process: Le patrimoine comme processus

- Part | Partie 3: Heritage as value: Le patrimoine comme valeur

- Part | Partie 4: Heritage as performance: Le patrimoine comme performance