![]()

CHAPTER 1

Expositions in German Colonialism and German Architecture

When we describe modernity and its effects, the image of the nineteenth-century exposition with its newfangled gadgets, milling flaneurs, and awestruck families immediately springs to mind.1 The same can be said of expositions and colonialism: it was through the characteristic phenomenon of the world’s fair that Europe’s colonial experiment came home to roost. From Paris to London, New York to Melbourne, and Kingston to Johannesburg, world’s fairs were iconic sites that showcased and stimulated the brave new world of industrial capitalism, rapid urbanization, and the creeping territorial expansion of European nation-states. Likewise, it is impossible to speak of modern architecture without speaking of expositions. Many of the technological and stylistic breakthroughs now understood as characteristic of modern architecture were associated with a specific exposition. Joseph Paxton’s prefabricated glass behemoth at London’s 1851 Great Exhibition, for example, frequently frames a narrative about the effects of new building materials and technologies and changing social and economic mandates. Following the 1867 Parisian exposition, German craftsmen and manufacturers recognized expositions as a new mass medium: by displaying complete room interiors at exhibitions at home and abroad, they attempted to transform bourgeois taste toward a new appreciation of the home as a venue for art. Moreover, as architectural historian Wallis Miller contends, expositions helped to formalize architectural collection and display as discrete professional activities for German architects.2 It was at these expositions that modernism’s design language and roster of protagonists was first established.

With this triple iconic status of the exposition in mind, this chapter discusses the development of the international exposition in a country not usually associated with the phenomenon: Germany. It shows that Germany participated actively in the so-called world’s fair craze by hosting numerous small-scale exhibitions modeled on the universal exposition. As was the case in Britain and France, these events became an important medium for spreading “the colonial idea.” And architecture enabled this process.

THE “EXHIBITIONARY COMPLEX”

Since their advent in the first half of the nineteenth century, expositions have been the subject of literary paeans, social critique, journalistic satire, and individual dreams and tragedies. Both period and present-day critics have devoted much energy to analyzing this fascinating genre. Fairs have been known for much of recorded human history, from religious celebrations in the ancient empires of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Mesoamerica to religious and military spectacles in the classical Greek and Roman worlds, and market fairs and carnivals in medieval Europe and in the African diaspora during transatlantic slavery. Something changed, however, in the nineteenth century. New fairs that had little to do with religious observances or traditional forms of commerce emerged. Over two hundred expositions as well as innumerable national, regional, and local exhibitions, trade and professional fairs, and other specialized exhibitions were held primarily in Europe between 1851 and 2001.3 It was through these fairs that new nations could imagine themselves in relation to their own pasts and to previous forms of community, and to neighboring societies and distant peoples, places, and times. What made the exposition unique was its condensed and hybrid character. Time and space were intensified in unprecedented ways that stimulated new kinds of communal and individual action. In his incisive analysis of the “exhibitionary complex,” Tony Bennett has argued that exhibitions were one of several intersecting institutional sites that inscribed and broadcasted a new message of power.4

Long before Bennett, German sociologist Georg Simmel had already argued that the international exposition was the definitive embodiment of modernity. In his view, the strategy of collecting an encyclopedic range of objects and experiences in a single place and time and thus creating a “momentary center of world civilization” was uniquely modern.5 Even as it aspired to encyclopedism, however, the exposition aimed to create a unified experience out of this alienating heterogeneity. New visual and spatial technologies—the building blocks of the soon-to-emerge modernism—emerged to harmonize this discord. Related to this was the simultaneously fleeting and permanent nature of the exposition, which was available for a finite period but left traces of itself in the physical fabric of the city and in the character of urban and global culture. Put another way, long after their closing, expositions still served the material function of the archive that had been part of their original purpose. Finally, Simmel argued that expositions were inherently globalizing in the way they fostered both collaborative and competitive interplay between individual and groups of states and nations.

Though Simmel did not specifically mention colonies, their presence epitomized the convergence of space and time that characterized the exposition for him. Colonialism was present in many forms at expositions—from the shocking corporeal presence of colonized people on exhibit to ethnographic ensembles that displayed the cultural products of the colonized, and manufactured cotton, rubber, and other products of alienated colonial labor. It is now clear that colonies represented more than a mere afterthought in expositions. Rather, their insistent appearance at world’s fairs illuminates their central role in European modernity.6 Using the occasion that inspired Simmel’s canonical reading, the 1896 Berlin Trade Exhibition, as a point of departure, this chapter shows that expositions played a similar role in Germany.

REPLICATING THE EXPOSITION: TYPE AND ARCHIVE

One feature that distinguished the 1896 Berlin exposition from its predecessors was the speed and completeness with which the idea and form were disseminated and reproduced. Bennett’s term exhibitionary complex hints at this rhizomatic aspect of the exposition. Expanding on Bennett’s ideas, historian Alexander Geppert replaces exhibitionary complex with exhibitionary networks in order to emphasize the “far-reaching internal references and formative transnational and interurban connections” that characterized the world’s fair.7 As he notes, these references were both conceptual and formal, and were perpetuated through print and other media and by individuals and organizations that moved across geographic and temporal boundaries.

Neither network nor complex, however, quite captures the archival workings of the exposition. Rather, the architectural concept of “type” seems more salient. Since the eighteenth century, architects have used type to explain continuity and change in architectural forms. Abbé Marc-Antoine Laugier’s discussion of the tree trunks and branches of the primitive hut as the archetype of the classical column and pediment and universal basis for architecture in his Essai sur l’architecture (1753) usually marks the beginning of architecture’s preoccupation with the concept. Other eighteenth-century architectural theorists, including Jacques-François Blondel, Antoine Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy, and Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand, used type to think through the relationship between causes, precedents, and models as they tried to come to terms with the expanding mandate of architecture in the modern era. By the late nineteenth century, the term again experienced a paradigm shift in response to a renewed focus on technology, economy, and production. More recently, in reaction to modernism’s inhumane functionalism, postmodern theorists like Aldo Rossi have revived type as a way to generate connections to the past in contemporary architecture and urban form.8

Even from its earliest mention, type has been closely associated with the exposition genre. This link is seen, for instance, in the work of Blondel, who included fairgrounds and vauxhalls as one of sixty-four types in his Lessons on Architecture (1771–1777). Both the traditional fairground and the newfangled vauxhall, or pleasure garden, of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century England were linked to the nascent public sphere and new ideas about commerce, science, and social order that culminated in the international exposition. Blondel’s embrace of the vauxhall in particular speaks to one of the underlying goals of his project: to elaborate an operative strategy for eighteenth-century needs that built on French architectural tradition.9 Blondel’s example reveals that the architectural idea of type emerged contemporaneously with the genre of the international exposition. That this link between type and expositions was well established may explain why the concept of type appears regularly in nineteenth-century German-language writing on expositions.

In Germany, exposition buildings were already considered a type by the date of publication of Ludwig Klasen’s classic catalog of building types, Grundriss-Vorbilder (1884–1896). Klasen distinguished fairgrounds of the past from new nineteenth-century spaces of public display and consumption. This new category, “Buildings for Art and Research,” included such novel subtypes as “art museums, museums for patent models, botanical and ethnographic museums, aquariums, libraries, archives, buildings for art exhibitions, buildings for international expositions, buildings for provincial exhibitions and county fairs, theaters, buildings for scientific observations and measurements, academies for learned societies, and ateliers for artists.”10

Klasen is most clear about what he means by “type” in his discussion of exposition buildings. The exposition type is a structure in which all the art and industry of a single society is exhibited. Like many subsequent writers, he relies on statistical, structural, and spatial comparisons between exposition buildings to identify the characteristics of the type: how did Cornelis Outshoorn’s Crystal Palace in Amsterdam (1855), for example, compare to Paxton’s Crystal Palace in London (1851) in span, square footage, and attendance? For Klasen, new developments in exposition planning and design were a response to the lessons from previous expositions. The result was a cycle of innovation and dissemination of the type.11

By analyzing these innovations, Klasen established a taxonomy and genealogy of exposition structures. His catalog included, among other subtypes, the all-inclusive multistory basilica with transepts (London, 1851), the “fishbone” main hall system consisting of a nave and multiple transepts (Vienna, 1873), and the infinitely expandable “pavilion system” (Berlin, 1883).12 Ultimately, in Klasen and other architects’ discussions, type was a shorthand for specific arrangements of form and function that responded equally to historical practices and contemporary needs. The reproduction, continuity, and differentiation of architecture is always already embodied in type. It is this open-ended quality that makes type useful in analyses of expositions. Because an originative idea is always retained in a type, typological analyses are helpful for tracing the dissemination and transformation of the exposition genre and architectural, spatial, material, and visual cultural developments associated with it. Thus, type helps to elucidate the peculiar “archivism” of both architecture and expositions.13 Conceptualizing colonial expositions as archives replete with types that have the ability to transcend space and time opens the door to appreciating the diverse and complex processes through which German architectural culture digested lessons from colonialism.

A WORLD’S FAIR IN GERMANY?: THE 1896 BERLIN TRADE EXHIBITION

It was not until the dawn of the new millennium and Hanover’s EXPO 2000 that Germany officially hosted a world’s fair. Yet between 1850 and 1930 German states, cities, professional organizations, and trade groups organized a plethora of exhibitions, which, in their individual form, content, and the personal and professional networks that brought them into being, developed on world’s fair practices. As German commentators like Franz Huber suggested, when taken together, these exhibitions performed much like a universal exposition.14 Typological analyses link German exhibitions to this larger tradition and reveal Germany’s investment in using the genre to advance its colonial and imperial projects. At the same time, expositions and their localized expressions in Germany were crucial sites for reformist architectural discourse.

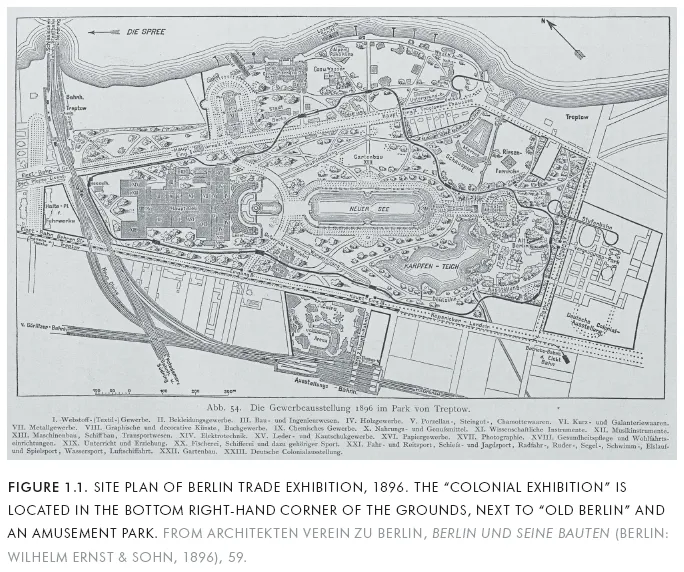

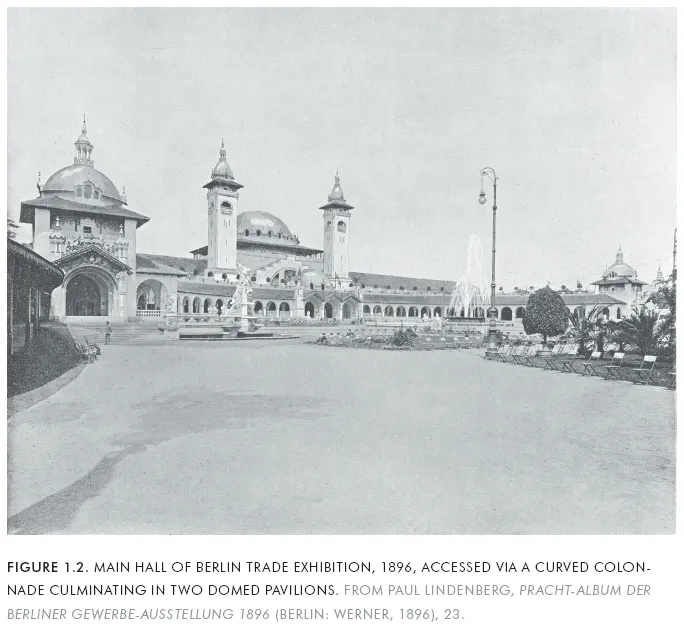

Treptower Park in southeastern Berlin is well known today as the location of the Soviet War Memorial (built 1946). In 1896, it was the venue of the city’s grandest public event, the Berlin Trade Exhibition. Between May 1 and October 15, Berlin hosted more than 7.4 million people on a 1.1-million-square-meter strip of land along the River Spree (figure 1.1). Visitors could approach the fenced complex from at least five major entrances, all of which were connected to a newly expanded rail and road network. Major attractions were located on all sides of a central artificial lake set amid rolling hills and verdant landscaping. A large exhibition hall dominated the western sector (figure 1.2). The long nave, subdivided aisles, and primary and subsidiary transepts of this building immediately establish its allegiance to the “basilica type” exposition building made famous by Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace. In front of the basilica in Treptower Park, however, was a sweeping colonnade that recalled the Trocadéro built for the Parisian exposition of 1878. Other elements of the Main Hall, such as its Byzantine massing, onion domes, and minaretlike towers, also point to the exotic Trocadéro, itself an eclectic combination of references including Islamic motifs.15

Exhibition organizers had commissioned Bruno Schmitz, a rising star known for designing royal and national memorials in a new, bombastic, monumental style to create the Main Hall in Berlin. The choice of Schmitz to design a building meant to represent German industry and culture to the world suggests that the organizers of the fair linked their commercial and political goals to questions of national identity. Schmitz collaborated with Ka...