![]()

ONE

Early Life and Career

FAMILY AND LOVE OF RAILROADS

Throughout his adult life John W. Barriger III took great pride in his family lineage, and he developed a keen interest in its genealogy. His first paternal forefather in America was Josiah Barriger (perhaps Bergere), who arrived in the New World from Holland during the colonial period. One ancestor, Samuel Huntington, a Connecticut jurist and governor, gained lasting fame as a signer of the Declaration of Independence. In the course of western migration the Barriger clan crossed the Appalachians and settled in northern and then western Kentucky. His grandmother Barriger claimed to be a descendent of Davy Crockett, the legendary Tennessee frontiersman and hero of the Alamo. On the maternal side, Beck family members also reached back to the pre–Revolutionary War era. These English immigrants did not scatter until later in the nineteenth century, staying for several generations in Maryland, mostly along the Eastern Shore.1

Barriger admired greatly his grandfather, John W. Barriger Sr. (1832–1906). This native Kentuckian graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1856, ranking an impressive thirteenth in a class of forty-nine. Unlike so many West Pointers, the senior Barriger made the US Army his career. Although initially in the artillery, he became a commissary of subsistence officer, being a logistics and supplies specialist. During the Civil War Barriger served with both regular and volunteer forces, rising rapidly in the latter to breveted brigadier general “for faithful and meritorious services.” Following the conflict he returned to the regular army but lost the temporary general rank and became a captain. Promotions, though, followed; he advanced from major to colonel in 1894. Like all military men, Barriger received numerous postings, including Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Missouri; New York City; and Washington, DC. During these post–Civil War years he displayed his talents as a researcher and writer, producing in 1876 a centennial history of the Subsistence Department. In 1896 Barriger retired from active service, although during the Spanish-American War the War Department recalled him temporarily to handle a desk job in Washington. Then in 1904 he became “Brigadier-General, US Army, Retired.” Barriger continued to be active, however. From his retirement home in New York City, he joined the editorial staff of the Army and Navy Journal, a publication that helped to professionalize the US military.2

Shortly after General Barriger’s death, a West Point classmate penned these insightful observations about his longtime friend: “His qualities of head and heart were such as soon to win the respect and esteem of his classmates, which the lapse of years never lessened. While always affable and courteous, he was as a cadet serious, thoughtful, studious and very conscientious in the performance of any duty.” These were personal traits that John W. Barriger Jr. and John W. Barriger III would share.3

The marriage of the senior Barriger to Sarah Frances Wright, who came from a military family and “had a distinguished Revolutionary ancestry,” took place at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, in 1863 and produced four children, three boys and a girl. John W. Barriger Jr. was the youngest of the couple’s three sons, born in Washington, DC, on July 20, 1874. His precollegiate education included schools on several army posts, but when his father was stationed at Jefferson Barracks, he completed his school career at Central High School in St. Louis. Unlike the vast majority of contemporary male high school graduates, he pursued a collegiate education. John Jr. selected Washington University in St. Louis and entered its developing School of Engineering. While he was attending the university, his father was transferred to New York City, but John Jr. found lodging with family friends in St. Louis.4

John W. Barriger Jr., however, did not graduate from Washington University. This was not due to poor academic performance but rather to a burning desire to launch a railroad career. In 1894, at age twenty, he joined the engineering department of the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis (TRRA) as an assistant to the resident engineer. It would be railroad entrepreneur Colonel Samuel W. Fordyce, a Civil War comrade of his father and family friend, who assisted in making this position possible. Although in the midst of the nation’s worst depression, the TRRA. was in the process of completing its St. Louis Union Station with its magnificent headhouse and massive train shed. This widely acclaimed facility opened officially on September 1, 1894. The initial assignment for John Jr. was to work on designing a complex series of tracks, crossings, and switches at the throat of the station. Next he turned his attention to the construction of a steel trestle that provided a connection between the station and the recently completed Merchants Bridge over the Mississippi River in north St. Louis.5

This photograph of the handsome John W. Barriger Jr. dates from 1898, a year before his marriage to Edith Forman Beck. (John W. Barriger III Collection, Barriger National Railroad Library at UMSL)

The relationship with Colonel Fordyce continued. When Fordyce became co-receiver of the Kansas City, Pittsburg & Gulf Railroad (KCP&G) in the late 1890s, John Jr. accepted his offer to join the company that somewhat earlier railroad visionary and promoter Arthur Stilwell had founded. Working in the engineering department, John Jr. participated in the survey of a projected line between Shreveport, Louisiana, and Beaumont and Port Arthur, Texas. His duties included those of rodman, compiler of statistics, and office manager. Following that undertaking, he joined the St. Louis Southwestern Railway (Cotton Belt), a carrier associated with Fordyce’s railroad ventures. His base of operation was Tyler, Texas, and here he held the position of assistant engineer, maintenance of way.6

Not only was the younger Barriger developing his professional skills, but his personal life was about to change. On the evening of April 3, 1899, he married the bright, attractive, and vivacious Edith Forman Beck in the First Presbyterian Church in St. Louis. Born in the Gateway City on Washington’s birthday 1877, his new wife was the daughter of Mary Forman Vickers, whose Baltimore family had been engaged in banking and shipping, and Clarence Benjamin Beck, a St. Louis fuel dealer who sold “bituminous and anthracite coal, coke and smithing coal.” Edith, the oldest of four children, two of whom died in infancy, received a solid liberal arts education, having attended Monticello Ladies’ Seminary, a Presbyterian female academy in Godfrey, Illinois, and the Mary Institute in St. Louis, a school affiliated with Washington University. Much later she would graduate from Washington University and eventually attend the law school of George Washington University in Washington, DC.7

A radiant Edith Forman Beck poses in her bridal gown and veil. Her marriage to John W. Barriger Jr. took place on Monday, April 3, 1899, at First Presbyterian Church in St. Louis, Missouri. (John W. Barriger III Collection, Barriger National Railroad Library at UMSL)

The newlyweds made their home in Tyler, Texas, and quickly their first child was conceived. On December 3, 1899, John W. Barriger III was born to John W. Barriger Jr. and Edith Beck. “That ‘blessed event’ occurred, I am told, while my mother was en route to return to her parents’ St. Louis home where better medical attention could be obtained than was available at that time in Tyler. But the stork would not wait a month, so my mother had to be taken off the train at Dallas and hurried to St. Paul’s Sanitarium, where I first saw the light of day.”8

Resembling so many railroaders, John Jr. led a nomadic life. In 1900 the family left Tyler for Kansas City, Missouri, and “lived in a little house on Vine Street [and] the scene of many happy memories for my mother.” The new job of the young husband and father was in the office of the chief engineer for the Kansas City Southern Railway, the company recently created out of the bankrupt Kansas City, Pittsburg & Gulf property, and where Colonel Fordyce served as Kansas City Southern’s first president. Edith Barriger recalled that her husband “was in charge of estimates for track, bridge and building work, together with masonry construction.” Then in March 1902 the family relocated to St. Louis. At this time Fordyce had become involved with the recently organized St. Louis, Memphis & Southeastern Railway (StLM&SE). This company, which consisted of several predecessor roads, planned to open a direct connection between St. Louis and Memphis, Tennessee, largely along the west bank of the Mississippi River. The junior Barriger supervised building its bridges, trestles, and structures. It did not take long, however, before the St. Louis–San Francisco Railroad (Frisco) took control of the StLM&SE, and John Jr. “was given a position of increased responsibility in its Engineering Department as Engineer of Bridges and Structures.”9

Unquestionably John W. Barriger Jr. possessed engineering talents. Yet he had others. Not only was he a skilled draftsman, but he made impressive pen and ink sketches of contemporary scenes “following [graphic artist] Charles Dana Gibson’s style.” Barriger was also a musician, playing such stringed instruments as the banjo, guitar, and mandolin. “He had a delight in music with a technical knowledge that marked him as an acceptable performer both for his own and other’s enjoyment.”10

On Friday, December 19, 1902, the promising life of John W. Barriger Jr. came to an abrupt end. That morning about ten o’clock a professional acquaintance, Thompson “Tom” McPheeters Morton, paid a call at his office on the fifth floor of the Granite Block at Fourth and Market streets in downtown St. Louis. The two men had previously worked together for the Kansas City Southern in Kansas City. But now an unemployed civil engineer, Morton hoped that Barriger could find him a job at the Frisco. For approximately ten minutes they talked, and Morton learned that there were no immediate openings. He also may have asked for a personal loan, something that Barriger had given him a few weeks earlier. At that point, workers in the adjoining drafting department noticed more than conversational voices. “Suddenly the men in the next room heard an oath blurted out in an angry tone, which was followed by a cry of terror,” reported the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. “They rushed to the door, where they saw Barriger standing at bay, his face distorted with fright, trying to ward off his assailant.” In his attempt to flee, Morton stabbed him twice with a common jack knife “of the barlow variety.” One cut penetrated Barriger about an inch or so to the left of his heart, and the other entered in the right side of his back and pierced his kidneys. Almost immediately Barriger’s coworkers wrestled Morton to the floor of the outside hall, and in the process he attempted suicide by digesting a compound of mercury pills. Morton, however, failed to end his own life. After he was subdued, these coworkers recognized that Morton had taken a suspicious substance. The assailant was rushed by the quickly summoned police to the St. Louis City Hospital, where his stomach was pumped. Nothing, though, could be done for the twenty-eight-year-old Barriger; he died in a pool of blood, victim of a tragic, brutal murder.11

A formal inquest followed. Testimony revealed that Tom Morton, who was thirty-one, single, a native of Shreveport, Louisiana, and “well educated,” suffered from mental illness. “Morton would lie on his back and make incoherent replies to questions,” observed Dr. H. L. Nietert, the St. Louis City Hospital superintendent, “and a few minutes afterward would revert to the same question again, and in a rambling way give another kind of a reply.” Family members concurred. His cousin, Judge William Beckner of Winchester, Kentucky, and a brother, C. H. Morton, a Presbyterian minister from Sweet Springs, Missouri, indicated that he “had been unbalanced mentally for some time.” Other witnesses reported that “Morton, once a talented civil engineer, had become a moral degenerate who expected others to provide him with an easy means of earning a living. Whisky and perhaps drugs have brought about the deterioration in his character.” It was indicated, too, that he was slightly deaf and “had a horror of being in the society of other people.” No member of the Barriger or Beck families attended the inquest; they believed that it would be too painful.12

The fate of Tom Morton surprised no one. In the ensuing trial the court issued its verdict. Rather than being sent to the Missouri penitentiary in Jefferson City where he might have faced execution for first-degree murder or more likely life imprisonment, Morton was committed to a mental hospital for the criminally insane. It had been a senseless crime, concluded the court, committed “in a seizure of insane rage.”13

The events of December 19, 1902, and the aftermath left deep and lasting emotional scars. The murder sent Edith Barriger into an extended period of mourning. “She wore heavy mourning for nearly ten years, including for several years a heavy black veil over her face whenever she went out,” recalled her son. “She occasionally mentioned to me what a terrible experience it was after kissing her husband goodbye when he left for his office in the morning to have his body brought home dead that afternoon.” No amount of sympathy, even the sadness expressed by the Morton family, seemed to raise her spirits. “Paradoxically this man [Tom Morton] was a member of a distinguished family in another State. Neither she nor I have ever divulged their family name. The family of this man was greatly distressed and offered most sincere condolences.” Her son also remembered that “she tried unsuccessfully to find solace in reading and writing.” Edith Barriger never remarried, dying in 1974 after more than seven decades of widowhood. Yet later she would have several boyfriends and male companions, including a married US Supreme Court justice.14

The immediate sting of that cold-blooded murder of John W. Barriger Jr. came at what should have been the most joyous time of the year, because it occurred only a few days before Christmas. At once, Edith and her three-year-old son left their home for a nearby family residence, and here they spent a most unhappy holiday. In a poignant commentary, John Barriger remembered that first Christmas after his father’s death. “My father, as a railroad man, possibly intending to cultivate an interest in trains in his infant son, had bought a mechanical one among the gifts intended to go under my Christmas tree. This last gift from my father was kept for many years along with a young children’s book entitled ‘The A.B.C.s of Railroads,’ which I still have, carefully bound.”15

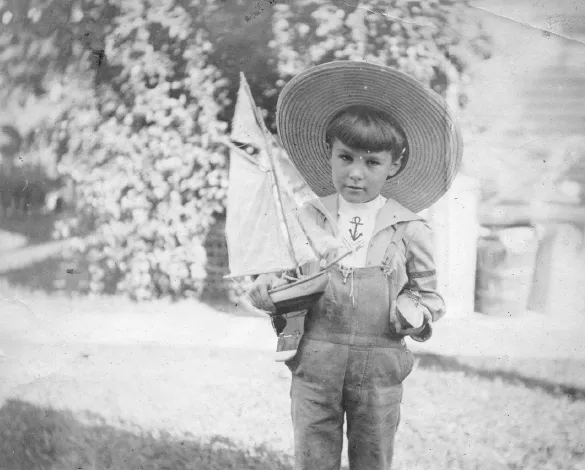

A young John W. Barriger III displays things nautical on a family outing to A...