![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Atypical Bodies

Constructing (ab)normalcy in the Renaissance

SIMONE CHESS

Malformed animals, conjoined twins, dwarfs, individuals with intersex conditions, several amputees, individuals with mobility impairments, a very fat bishop, two hunchbacks, and a pig-faced woman: representations of early modern atypicality ran the gamut from marvelous to mundane, from abstract to everyday. In this chapter, I will discuss only a small representative sampling of the many types of non-normative bodies that were recorded, discussed, fictionalized, and illustrated in early modern literary and cultural texts, in each case seeking to identify theoretical, psychological, and emotional cruxes in the representations of these atypical bodies. Were so-called monstrous births miracles, messages, or medical phenomena? Were adults with visible disabilities objects of pity or protagonists with power and potential? Could atypical bodies be seen as sexual or romanticized, or need they always be unsexed and isolated? Early modern literary and cultural texts demonstrate an understanding of disability and disfigurement at the tipping point between social/cultural and medical models, where atypical bodies are simultaneously discussed as spiritual metaphors and as medical conditions, and where suggested “cures” for atypicality vary from medicalization to moralization through acceptance, accommodation, and even valorization. In this way, sixteenth- and seventeenth-century depictions and discussions of atypicality are very much early modern; they articulate approaches to disability that are simultaneously fixed and fluid, medical and magical, individual and relational, negative and optimistic.

In terms of typicality as a term and idea, the Renaissance is at the cusp of a major change in how normalcy and abnormalcy are understood, categorized, and pathologized. Lennard Davis argues that:

Before the early to mid-nineteenth century, Western society lacked a concept of normalcy … Before the rise of normalcy … there appears not to have been a concept of the normal, but instead the regnant paradigm was one revolving around the word “ideal.” If one has a concept of the “ideal,” then all human beings fall below that standard and so exist in varying degrees of imperfection. The key point is that in a culture of the “ideal,” physical imperfections are not seen as absolute but as part of a descending continuum from top to bottom. No one, for example, can have an ideal body, and therefore no one has to have an ideal body. (2002: 105)1

Arguments like Davis’, together with reminders from premodern disability studies that disability was more visible, more common, and more public in the medieval and early modern periods, can give the impression that early moderns did not see or make distinctions about disability and atypicality in the way that we do today.2 But early moderns were in fact very aware of the difference between bodies that were simply imperfect and those that they saw as monstrous, deformed, amazing, or disgusting.3 In her analysis and itemization of medical language just in Shakespeare’s works, for example, Sujata Iyengar catalogues 391 disorders ranging from scabs to gout to earwax. At the same time, she acknowledges that “if we are interested in early modern embodiment, we have to consider not only the pathological body but the healthy one, and to historicize the early modern body. That is to say, the body and its processes, diseases and appearances are not themselves immutable and unchanging, but are themselves formed by different social, historical, and political forces” (Iyengar 2014: 1). But all approaches to ability and disability are similarly historically bound. As Tobin Siebers puts it, “To call disability an identity is to recognize that it is not a biological or natural property but an elastic social category both subject to social control and capable of effecting social change” (2008: 4).

If normalcy and deformity, disability and able-bodiedness are all subjective and historically bound, what is the benefit of identifying and examining early modern atypicality? Allison Hobgood and David Houston Wood have proposed that “Renaissance cultural representations of non-standard bodies might provide new models for theorizing disability that are simultaneously more inclusive and more specific than those currently available” (2013a: 10).4 Early modern attitudes toward atypical bodies can help us historicize contemporary crip and disability representation and experience; at the same time, some early modern texts can provide models for acceptance and inclusion, strategic adaptation, and empathetic identification. Instances of early modern atypicality, then, have the potential to undermine assumptions of linear progress toward disability justice, to disrupt historical stereotypes, and to contribute to the goal of a broader and less fixed cross-historical disability studies.

1.1. MONSTROUS BIRTHS: METAPHOR AND MEDICALIZATION

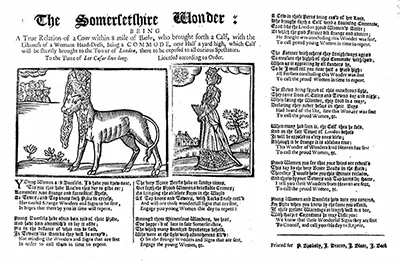

Atypical bodies are celebrated and scrutinized in early modern ballad and broadsides—cheap print texts, often set to music and accompanied by woodcut images—that were sold for popular entertainment, but these representations run the gamut from moralistic and voyeuristic approaches to the body to more complex and nuanced depictions of atypicality. These cheap print formats capture popular fascination with bodies of all kinds, but particularly with bodies born with fetal abnormalities. The ballads in the “monstrous births” genre show emerging attitudes about atypicality, ranging from heavily moralizing interpretations of some births to frank medical analyzes of others; in this array of approaches, they are similar to modern media approaches toward atypicality, which range from exploitative tabloid scandal to “informative” popular science.5 On the extreme end of metaphorical representation are descriptions of births that seem almost entirely to contain heavily moral messages conveyed through the device of the marvelous birth; these representations care less about the atypical body itself and more for the messages it is seen to convey to its audience of readers and interpolators. Two prime examples of this mode of analysis are the ballads “A Fair Warning for Pride” (Pepys 4.310) and “The Sommersetshire Wonder” (Pepys 4.362).6 Both ballads depict farm animals born with craniofacial malformations that look like popular (and popularly derided) women’s hairstyles, and both present the animals more as messages to women than as creatures in their own rights.

In “A Fair Warning for Pride,” the author turns monstrosity away from the malformed foal and toward its audience, addressing “O Monstrous Women!” and asking,

why will you offend

Your Maker, who many sad Judgements may send

Upon the whole Nation, for your sin of Pride.

According to the ballad’s speaker, women’s

Laces, nay, Towers and Top-knots beside:

So Gawdy you are, when drest in your Hair,

That good sober Christians you perfectly scare;

The wrath of high Heaven you have cause to fear.

Thus, as we learn from the ballad’s chorus, God’s reaction to the vanity of topknot-wearers is made manifest through the atypical body of the foal, whose malformation is described in great detail:

Altho’ it be Flesh, yet like Ribbons it Curl’d;

Of several Colours, full seven indeed,

And when they are handl’d they presently bleed:

And likewise again, from the Head to the Main,

The likeness of Ribbon is perfectly plain.

At the end of the ballad, the foal is brought to Bartholomew Fair, where its body will be staged for profit, entertainment, and, at least in theory, to spread its message about fashion and pride.7 The birth of an atypical calf is similarly metaphorized in “The Somerset Wonder.” Rather than a topknot, the calf is born with a malformation resembling an ornate “commode” headdress measuring “near half a Yard high.” Again, the atypical form of the animal is immediately interpreted as a lesson for young women about their prideful attire. Interestingly, where the woodcut illustration (Figure 1.1) of the foal shows its malformation as resembling a topknot in a way where, while ribbon-like, it still might be an unusual growth, the illustration of the calf (Figure 1.2) shows its growth to be symmetrical, flowing, and carefully patterned with decorative lace. The image therefore confirms that the ballad’s purpose is less to describe the calf’s birth with realism or scientific detail, but rather to emphasize a moral message made possible through the animal’s shape at birth. Both the foal and the calf are displayed first by farmers and fairgoers at the time of their births and then in perpetuity through the ballads and their woodcuts. The atypical body serves as a rhetorical tool, a device through which social values are interpolated and reinforced.

FIGURE 1.1 Woodcut image of a foal with a topknot, from “A Fair Warning for Pride” (Pepys 4.310). By permission of the Pepys Library, Magdalene College Cambridge.

FIGURE 1.2 Woodcut image of a calf with a headdress, from “The Sommersetshire Wonder” (Pepys 4.362). By permission of the Pepys Library, Magdalene College Cambridge.

In his 1627 satirical poem “The Moone-Calfe,” Michael Drayton uses rhetoric similar to these metaphorized ballads as a way of conveying his own social commentary. From its very title, the poem gestures at bodily difference and deformity: the term “mooncalf” is most well known for Shakespeare’s use of it in describing Caliban in The Tempest. While it stands for general monstrosity in that play, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) gives a more specific association with birth defect, giving the definition “a false conception.”8 The poem plays on this idea of defective conception and reproduction as it opens with the image of the earth, personified, pregnant, and in the throes of labor: “The World’s in labour, her throwes come so thick, / That with the Pangues she’s waxt starke lunatic” (1627: 153).

Even before the world gives birth, Drayton describes her body, attire, and promiscuity as grotesque: she is “Stuff’d with infection, rottennesse, and stench” (153), clothed in “a Fooles coate, and cap” (153), and her child will be a bastard because “there’s not a Nation / But hath with her committed fornication” (156). As the earth labors, her contractions described as earthquakes and thunder and avalanches, she confesses that the devil is the true father of her child. With the stage thus set for a monstrous birth, Drayton ends the poem by describing the baby:

And long it was not ere there came to light,

The most abhorrid, the most fearefull sight

That ever eye beheld, a birth so strange,

That at the view, it made their lookes to change;

Women (quoth one) stand of, and come not neere it,

The Devill if he saw it, sure would feare it;

For by the shape, for ought that I can gather,

The Childe is able to affright the Father;

Out cries another, now for God’s sake hide it,

It is so ugly we may not abide it. (157)

Drayton builds his satire from labor to birth, and then suspends the actual presentation of the monstrous birth; rather than revealing the baby and its body, he shows instead a scene of viewing, where a crowd observes it in shock and terror. In this way, even as he emphasizes the metaphor of the poem—that earth is corrupt, and that the corruption is culminating with monstrous results—he simultaneously demonstrates the power of the atypical body to capture the stare of a broad audience, and to impact each viewer in a deep way. This is the type of “staring” at atypicality that Rosemarie Garland-Thomson has described, where “The sight of an unexpected body—that is to say, a body that does not conform to our expectations for an ordinary body—is compelling because it disorders expectations. Such disorder is at once novel and disturbing” (2009: 37). Yet, while Garland-Thomson is explaining a response to atypicality that can feel typical or universal, she also locates the Renaissance as a tipping point in the meaning of that staring gaze. She argues:

As the seventeenth-century took hold, seeing developed new forms in a secularizing, democratizing world. Observation replaced witnessing with the rise of rationalism and scientific inquiry … The modernizing world celebrated earthly rather than heavenly sights in art and technology. The early modern period gave us perspective … thus perspective helps to transform the individual viewer into a gatekeeper of knowledge regarding the scene depicted, shutting down the possibility of competing knowledges that might emerge from the multiple points of view suggested by medieval painting or, later, cubist art. (2009: 27–8)9

Drayton’s poem enacts the exact point of transition that Garland-Thomson suggests, so that even though the gods and the devil are among the audience staring at Earth’s monstrous birth, all observers’ views have equal authority. Knowledge of the child, its body, and its significance can be gained, in the poem (and increasingly in the period) both through an interpretation of the body’s symbolic meaning and through anatomical observation and analysis. In her d...