![]()

I

THE MONUMENTS

THE MAUSOLEUM OF AUGUSTUS

IN 29 B.C., TWO years after conquering Mark Antony and Cleopatra, Augustus (then Octavian) returned to Rome to celebrate a triple triumph for his victory at Actium, the annexation of Egypt, and his conquest of Illyricum. Determined to establish himself in supreme power, he undertook the task of rebuilding the shaken city. Though neither he nor his minister of works, Agrippa, was new to the art of building in Rome, this initiative on his return tackled the city’s infrastructure and urban image with unprecedented vigor. Completing Julius Caesar’s Curia and a Temple to the Divine Julius in the Roman Forum in 29, in 28 Augustus turned his attention to a Temple of Apollo, his epiphanous patron at Actium, as one of eighty-two temples he later claimed to have built or restored. Work on the Campus Martius began in earnest with the restoration of Pompey’s vast triumphal complex and the provision, in 25, of public amenities such as the Thermae Agrippae and the Basilica Neptuni. Also in 28, Agrippa began the first Pantheon and dedicated it in 25 as a cult center for all the gods, including Augustus’s mortal predecessor, Julius Caesar.1 To the north of this, as one of the first buildings of this extensive program, Augustus constructed a magnificent Mausoleum for himself and his family (figs. 2, 3). Its doors opened in 23 B.C. when Marcellus, Augustus’s nephew, died prematurely, and it found constant use over the next two decades as, one by one, Augustus’s descendants predeceased him; finally, in A.D. 14, he was laid to rest there himself.2 The long years since its construction have not been kind, and, despoiled of its revetment in the Middle Ages when it was a marble workshop (the Calcare dell’Agosta), it has been used as a fortress for the Colonna family, a hanging garden, a bullring, amphitheater, and concert hall. Excavated in 1907–8 and 1926–30, it was finally “liberated” by Mussolini in 1939.3

Soon after its construction, Strabo wrote:

Most worth seeing is the so-called Mausoleion, a large mound set upon a tall socle by the river, planted with evergreen trees up to the top. Above stands the bronze statue of the Emperor Augustus. Within the mound are the graves intended for him, his relatives, and friends. Behind there is a large grove with splendid walks, in the midst of which is an elevated place (the ustrinum), where Augustus’s corpse was burnt.4

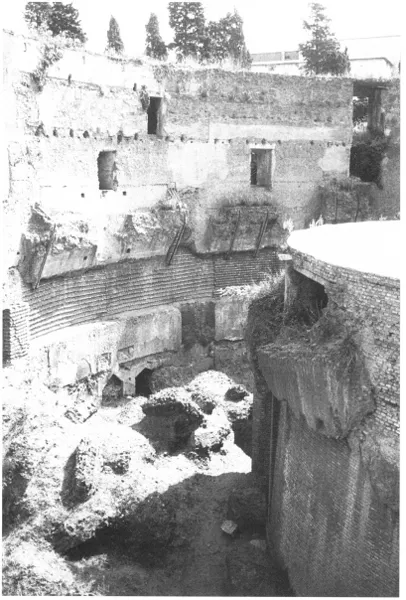

Figure 2. Mausoleum of Augustus, Rome, ca 28 B.C., actual state. Photo: Penelope J. E. Davies

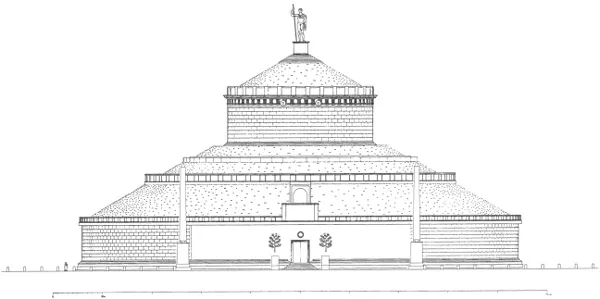

Reconstructions of the tomb have traditionally fallen into two main camps.5 One sees the tomb as a simple earthen tumulus planted with grass and black cypress trees, surmounting a two-tiered circular base wall with a decorative entablature.6 More convincing are reconstructions with greater architectonic articulation, most recently Henner von Hesberg’s (fig. 4). This posits a masonry drum reveted with travertine and with Carrara marble to either side of the entrance, where inscriptions named those interred inside. Above the drum rose the grass tumulus, broken by a ring of masonry above walls 4 and 3. Above wall 2 was a tholos with a Doric entablature and crenellations. The tumulus continued above the tholos, and at the apex were steps and a statue of Augustus on a podium, melted down in the Middle Ages. Sparse fragments of surviving sculptural decoration are comprehensively catalogued by Panciera.7

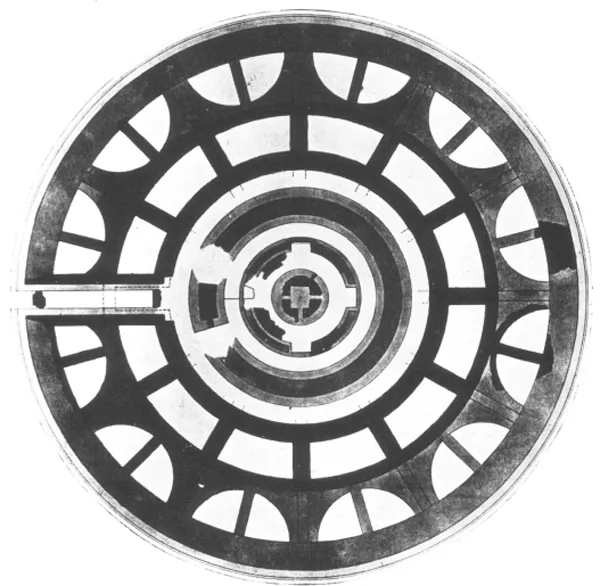

In plan, five concentric walls (the outermost 300 Roman feet in diameter) surrounded a 150-foot-high rectangular travertine pillar, coated with concrete to appear cylindrical above ground level (fig. 5).8 From the entrance on the south, a vaulted vestibule led to an annular corridor between walls 2 and 1. From this passageway one entered the burial chamber proper, which contained niches for urns or statuary at the cardinal points. Inside the travertine pillar in the center of the cella was a smaller chamber, presumably for Augustus’s cinerary urn.9 Between walls 5 and 4 were semicircular chambers divided by radial walls to make quarter circles, and radial walls also linked walls 4 and 3 to form 12 rectangular chambers. There was no access to either set of chambers.

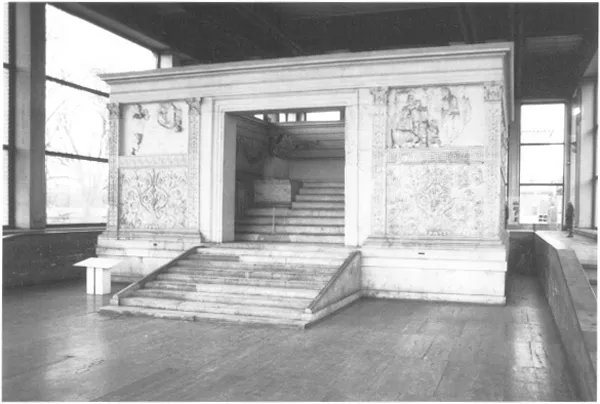

Just outside the entrance to the Mausoleum was a pair of pillars on which a copy of Augustus’s Res Gestae, or Things Achieved, was inscribed after his death as specified in his will. This document, which Augustus updated gradually throughout his reign, detailed honors and offices he received, his personal expenditure for public good, and his military accomplishments.10 Flanking the pillars, and standing some 22 meters from either side of the entrance, was a pair of small, uninscribed red granite obelisks (figs. 6, 7).11

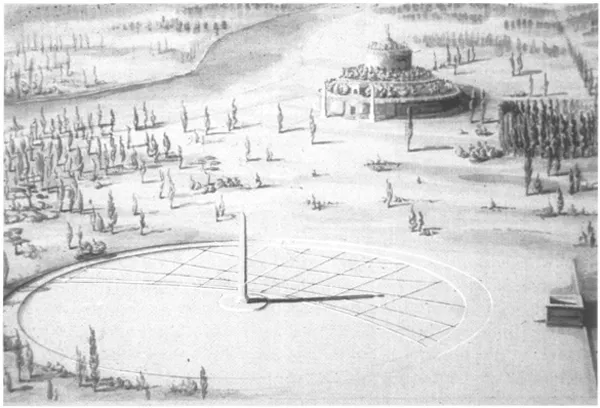

The Mausoleum did not stand in isolation on the northern Campus Martius; rather, as Edmund Buchner and other scholars have suggested, it was but one component of a tripartite complex, consisting also of the Ara Pacis Augustae and Solarium or Horologium Augusti. The Ara Pacis or Altar of Augustan Peace (13–9 B.C.), a small marble altar within a hypaethral rectangular enclosure, celebrated Augustus’s safe return from Spain and Gaul (fig. 8). Lavish relief sculpture ornaments the entire monument. On the lower half of the exterior of the enclosure wall is a rich carpet of acanthus. In the upper register, four panels flank the doors on east and west sides: on the west, Aeneas sacrifices on his arrival in Latium, and the she-wolf suckles Romulus and Remus; on the east, two seated figures represent the goddess Roma and a female of disputed identity, nursing two infants and surrounded by animals, vegetation, and two female personifications of winds or seasons (fig. 82). Friezes on north and south sides depict a procession of priests, senators, and imperial personages (fig. 78). The interior of the enclosure is carved to imitate wooden laths and pilasters, decorated with bucrania, garlands, and paterae (fig. 73), and a procession in honor of peace winds around the altar itself.12 The Solarium or Sundial (10–9 B.C.), for its part, consisted of a huge bronze grid laid into the pavement around an Egyptian obelisk, with mosaics of the winds and various celestial symbols (figs. 9, 60–61).13 Though constructed over a period of approximately twenty years, the monuments were visibly united by their topographical proximity to one another and their isolation from other buildings (since the area around them was desolate), even if they were not joined by the movement of the needle’s shadow, as Buchner supposed. They also shared commonalities in symbolic themes, such as references to the Actian victory. All, we might suppose, were part of Augustus’s commemorative scheme.14

Figure 3. Mausoleum of Augustus, Rome, ca 28 B.C., actual state. Photo: Penelope J. E. Davies

Figure 4. Reconstruction of the Mausoleum of Augustus by H. von Hesberg. Courtesy of Henner von Hesberg

Figure 5. Plan of the Mausoleum of Augustus, Rome, ca. 28 B.C., actual state.

Photo: Deutsches Archaologisches Institut, Rom–InstNegNr 61.1181

Figure 6. Obelisk from the Mausoleum of Augustus in Piazza dell’Esquilino, Rome. Photo: Penelope J. E. Davies

Figure 7. Obelisk from the Mausoleum of Augustus in Piazza del Quirinale, Rome. Photo: Penelope J. E. Davies

Figure 8. Ara Pacis Augustae, Rome, 13–9 B.C., view of the west side. Photo: Michael Larvey

Figure 9. Reconstruction of the Solarium Augusti with the Mausoleum of Augustus and the Ara Pacis Augustae, Campus Martius, Rome, ca. 28–9 B.C., by E. Buchner. Courtesy of Edmund Buchner

Tiberius’s ashes, and probably those of Claudius as well, joined Augustus’s in the Mausoleum, a testimony to the dynastic basis of Julio-Claudian authority.15 Following Caligula’s assassination in 41, his body was “carried away secretly to the Lamian Gardens and, half-cremated on a hastily-built pyre, it was buried under shallow turf. Later, it...