![]() Part 1

Part 1

THE FLORESCENCE OF MAYA SPIRITUALITY![]()

CHAPTER 1

A New Cycle of Light

The Public Emergence of Maya Spirituality

I was waiting outside the popular Doña Luisa restaurant in Antigua at 7:00 a.m. when I saw the energetic figure approaching down the cobblestone street lined with adobe and Spanish tiled-roof shops. From his deliberate, quick gait, I recognized Martín Chacach, a Kaqchikel-Maya linguist from the University of Rafael Landívar whom I had met a month before in Quetzaltenango. He had delivered a lecture to a group of young Maya bilingual educators on the resurgence of Maya culture. We exchanged greetings, and then he motioned for us to enter the colonial courtyard. We took seats at one of the tables along the patio wall and each ordered a cup of coffee. Small groups of middle-aged tourists and young students were beginning their day over breakfast in the open-air courtyard, bright and warm with morning light.

“Don Martín, thank you for meeting with me this morning,” I began. “As I mentioned to you, I want to talk with you about the rebirth of Maya spirituality.”

“Yes, recently Maya have been public, drawing their spirituality out into the light,” he commenced. “It’s evident at the initiation of cultural and national events. Groups are using the services of the Ajq’ijab’ so that their activities are successful, asking God that all should go well. There is a rebirth, a new dawning of Maya spirituality, philosophy, and cultural pride in Guatemala. In fact, it is a movement that can not be stopped.”

“And what is the root of this emergence?” I asked, pressing to understand.

Don Martín paused, took a sip of coffee, and set the cup on the table. “It’s about understanding our own philosophy, how our world is in relation to God, to nature, to humanity. We lost much, we did not lose ourselves, but we lost much that is a dynamic form of life over five hundred years. It was an attitude. Colonized, we were not able to speak. But now, we look around us and reassess our lives. We begin to make comparisons to establish and maintain a cosmic equilibrium.”

“What do you mean, you make comparisons?” I asked, puzzled.

“We see one single plant, one human being, one fruit, yet we recognize that we all share in the life of one another. If we take care of the plants, they will take care of us. In our way of understanding, we wake up in the morning, greet the four points, Señor Tat, the sun. We greet adults in the house, in the street. We greet one another with the same respect.

“You and I understand that every child is conceived at a particular time and place, so there is no doubt that this person has a distinct cultural root. But if one considers, as we Maya do, that all this is bound up with what happens in the cosmos, it is not simply a cultural question. It is beyond culture, into a cosmological reality. It would be good to have a conference with Hindus, with Buddhists, to see that it is part of a larger feeling, a larger ecological reality.

“This rebirth of Maya culture, spirituality, and intellectuality,” he continued, redirecting the conversation, “is bound to the will of the people. It is a dynamic process and has a life, like the life of a people. It ebbs and flows. We have to use Maya resources, resources of the people and of the world. The life of all people emerges and dissipates. For example, the United States has the power now, but for how long will it have this power?

“In my case, my parents were very Catholic. I grew up in the country, but was not exposed to Maya spiritual ways. It was not affirmed, so now I am reclaiming it.”

“Do you think that there are more Maya Ajq’ijab’ now?” I inquired.

“Yes. I also think Ajq’ijab’ have to be more public. Now, most practice their spirituality privately. Catholics have their masses on television; fundamentalists broadcast their predictions on television. Why don’t we have Maya ceremonies on television? Maya spirituality must have public light. People need to know our spirituality, not as folklore, nor as a tourist event, but as an integral part of our cultural lives.”

“What are the obstacles to this reemergence?” I asked.

“I see with good eyes,” he continued, nodding, then looking into the distance. “We have some obstacles. Our people are poor. We need teachers, curricular guides, and schools. Poverty doesn’t allow it to happen. We need economic support from other countries. At this historical moment, we have to heal. We have our own existence; but also others, too, have to support our existence. This is the process of peace. Each culture has a right to be. This is the balance that we look for. We have to look at our spirituality because there we find our philosophy, our dialogues, our rituals.”

He glanced at his watch. Knowing he had to catch a bus soon, I thanked him. We bid one another farewell. Don Chacach picked up his briefcase and headed to Guatemala City.

THE PUBLIC EMERGENCE OF MAYA SPIRITUALITY

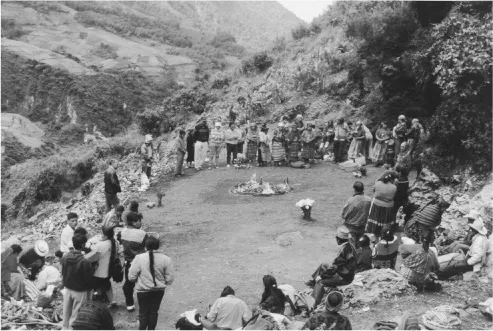

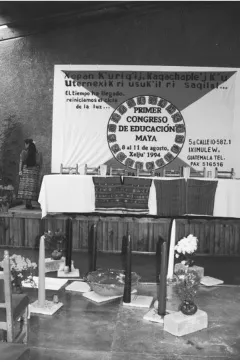

At dawn at a selected altar in the Guatemalan highlands, a gathering of people, led by Ajq’ijab’, encircle a fire and in prayer remember the names of ancestors, recalling their suffering, silence, persistent patience, and endurance. They lift up their hearts and voices in thanksgiving to petition and procure strength before the rising flames and incense. Nearby in the city of Quetzaltenango, on 4 K’anil, the day of the 260-day sacred calendar on which the new proprietors decided to open their small cafe, the invited Ajq’ij directs the owners to place red, black, white, and yellow candles and flowers in designated four corners and set the blue and green ones in the center, as family and friends gather for a ceremony of initiation. In Patzun, an embroiderer raises a silver needle, the yellow thread catching the light, and pierces the red-and-white striped woven cloth; she brocades the next glyph of the twenty-day signs circling the neckline of a huipil (woven and embroidered blouse). In Sololá, an Ajq’ij runs her hands across the tz’ite’ beans, and in counting the days and attending to the movements in her body, advises the troubled client. In Salcaja, an Ajq’ij is invited to explain Maya spirituality to Presbyterian seminarians; the next week, he addresses students on the Maya calendar at the University of Rafael Landívar in Guatemala City. In recent years Ajq’ijab’ have prayed publicly with widows and children before their husbands and sons’ assassinated bodies are exhumed from mass graves. Thousands of miles to the north, in Mission Dolores Park in San Francisco, California, eighty people gather at dawn around the fire as the transnational Ajq’ij explains the significance of the Maya New Year ceremony. In every instance, indigenous cosmovision is being brought to a new, liberating expression. Maya who interpret their lives in cycles of time, in folds of darkness and light, speak of a new cycle of light, a florescence of Maya identity, culture, and spirituality. “For the Maya, things are hidden, revealed, hidden, revealed,” explains Miguel Matías, a Kanjobal Ajq’ij. “This is a time of manifestation.” (See Figures 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3.)

What marks this public emergence of Maya spiritual practices since the mid-1980s in Guatemala? To appreciate fully the significance of these now open acts requires us to situate the recent historical context, to examine the social and political processes for this current emergence, and to ask the question: Why is it happening at this historical juncture?

FIGURE 1.1. A community gathers at Chuwi pek for a Wajxaqib’ B’atz ceremony in Zunil.

Emergence, the coming out from a hidden realm to the light above, echoes the activity of the ancient Mesoamerican ball game, where the ball symbolizes the disappearance of the sun into the underworld and its rising after a nightly journey through the darkness. The planted kernel of corn also replicates emergence as it germinates in the dark, moist soil, surfaces into light, and sprouts stalk, leaves, ears, and tassels. Emergence is the exploration and expression of all potentialities for life.

Philosophers and scientists in the West labor to interpret the increased complexity emerging in the universe over 14.5 billion years. From matter, life, mind, and consciousness, spirit emerges in slow progressions. Process theologians and scientists explain that disorder is a condition for the emergence of new forms of order, further extending the concept. Michel Foucault wrote that emergence designates the moment of an arising, and “is always produced through a particular stage of forces” (1985, 83).

I will borrow a framework from Dr. George Ellis,1 who discusses the activity of emergence in his Five Levels of Emergence within the universe, to show this development.

His paradigm understands human community as a group of complex and comprehensive systems which have finally become selves. These selves are conscious, knowing, loving, free, volitional, and responsible agents. For Ellis, in the process of emergence, existence is a feedback control system which assumes or requires reflective humanity interacting in an ecological environment, while striving toward explicit goals. These goals, which are related to memory, are influenced by specific events in individual history. For humans—as distinct from other living organisms—these goals have been explicitly experienced through language systems, and are determined by a symbolic understanding of complex modeling of the physical and social environment. Therefore, we can say that culture, informed by language and symbol making, shapes the neurology as well as the neurological development, of individuals. I understand the contemporary reclamation of Maya cosmovision to be a specific example of Ellis’ formulation.

FIGURE 1.2. Maya educators held the First Congress of Maya Education in Xelajú (Quetzaltenango), Guatemala, August 8–11, 1994. The banner announces, “The time has arrived. We reinitiate the cycle of the light …”

FIGURE 1.3. Norma Quixtán de Chojoj was elected governor of Quetzaltenango (Xelajú) in 2003; in April 2005 she was appointed Secretary of Peace, a national position created in 1997 to oversee the Peace Accords. She is founder and director of Centro de la Mujer Belejeb’ B’atz, an association of indigenous women in Quetzaltenango area whose goal is to gain cultural, economic, and political rights. Photo courtesy of Norma Quixtán de Chojoj.

People develop forms of consciousness, which are distinct as they relate to a particular geography and community. As we shall see, at this historical juncture, some Maya have begun to reexamine their ancestral ways and spirituality in order to clarify their distinct cosmovision (worldview). This human consciousness, which is knowing, loving, and willed, is a consciousness that wants to survive, to carry on.

This emergence is linked to the question of identity, a people’s insistence to understand what it is to be human within a particular history, geography, and memory. On the heels of a civil war marked by ethnocide of the Maya, in the midst of a national shift from the dominant religious ideology of Roman Catholicism to a growing Protestant Pentecostal population and of the country’s deeper involvement in transnational hemispheric processes, individuals and communities are articulating their difference and constructing new political and social space. Maya are taking into account the experience of themselves as sentient subjects in the natural world. They have developed a relatedness to creation and in turn engendered profound attunement, respect, and gratitude. Secure in their embodied relational consciousness, they want this perception to survive, be brought into light, amplified, and passed on.

This rejuvenation and public visibility of ancestral spirituality is marked by an increase of private and public communal ceremonies; the recuperation, reclamation, and daily use of the Chol Q’ij, the 260-day sacred calendar; and the commitment of more women and men, of diverse ages and professions, backgrounds, from rural and urban areas, to undertaking lives as Ajq’ijab’. It is no longer strange to see Maya rituals or interviews with Ajq’ijab’ on front pages of national newspapers or broadcast on national television networks. Alvaro Colom, second runner-up for the 2003 Guatemalan national presidential elections, was publicly recognized as an Ajq’ij. Ajq’ijab’, invited by various Maya communities in diaspora, indigenous, university, or religious groups in the Americas or in Western Europe, cross geographical boundaries to support, pray with, and advise Maya in exile, or to lecture, share ceremonies, and help those who seek their counsel.

The historical context of this emergence is noteworthy.2 Under Spanish colonialism, the Church, charged by the Crown with converting the Maya and protecting them from colonists, imposed hegemonic political, economic, and religious forms and controls for purposes of tribute, production, and labor over indigenous communities, which mirrored secular colonization (see Ricard 1966; MacLeod 1973, 120–122; Farris 1984; Lovell 1992, 72–73; Oss 1986, 14–17; Meyer 1989; Watanabe 1992, 42–58; R. Carlsen 1997b, 71–100). From 1871 to 1926, anticlerical Liberals took a number of steps to undermine the Catholic Church. In the 1870s, Catholic religious orders were expelled, Jesuit landholdings were nationalized, and monasteries were abolished. Liberals encouraged Protestants from North America and northern Europe to immigrate and establish their projects in Guatemala (Garrard-Burnett 1988, 1–46; Steigenga 1999, 152–153). The anti-Catholic rhetoric of the Protestant missionaries did not win them large numbers of converts, but did create divisions between traditional Maya leaders and those associated with Protestant missionaries. After the 1870s, highland Maya religious leaders and laypersons directed religious activities, with clergy appearing annually to baptize and marry people.

The hegemony of the Catholic Church, as it neglected many highland towns, ebbed and fractured during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century (Watanabe 1992, 185). Mid-twentieth century, the institutional Church reemerged due to two processes. The Church, now viewed by state and ecclesiastical authorities as less radical, even as anticommunist, developed ties with the government and elite interests of the country. Second, due to the paucity of Guatemalan priests, the Church invited priests from Europe and the United States to reconstitute local congregations through social and spiritual programs (186). Handy writes that “by the late 1960s, only slightly over 15 percent of the [415] Guatemalan clergy were native born. The most important foreign sources of priests were Spanish Jesuits and American Maryknoll fathers” (1984, 239).

By the time of the U.S.-backed coup in 1954, when progressive Jacobo Arbenz was Guatemala’s president, the conservative national Catholic hierarchy had initiated Acción Católica (Catholic Action), a reform movement that could not be easily stopped. Its original intent was to bring Maya back to observance as defined in Rome and to stem the tide of radical peasant politics that were gaining popularity in the countryside. To bring popular religion closer to the orthodoxy of Roman Catholicism, Catholic Action was launched as a large-scale catechist movement in the highlands, “comparable” writes Wilson, “to the first evangelization of the 1530s. … By becoming catechists, indigenous lay Christians played a role they had not enjoyed since the 1530s” (1995, 174).

Catechists not only challenged the traditional community religious practices and civil-religious order, but the entire village power structure. Catechists gained access to village authority and prestige, monopolized relations between the parish and the community, and marginalized elders and practices of costumbre (ancestral beliefs), often in extremely zealous actions. Catholic Action attacked native religious organizations. Zealots destroyed Maya altars; followers of costumbre were ridiculed and punished in public (Watanabe 1992, 204). Catholic priests attacked Ajq’ijab’ as agents of the devil. In some villages, catechists destroyed images, and elders were prohibited from higher positions of responsibility.

Don Pedro Calel, keeper of the calendar in Santa María Chiquimula, related to me the effect of Catholic Action in Santa María when a new priest arrived in 1952. “The priest didn’t appreciate Maya. He threw the candles away. He even went to the municipal court; then we couldn’t practice our religion anymore. He stayed six to eight years.” Don Pedro continues:

After Catholic Action in 1952 when the priest threw out all the candles and went to court so it was illegal to practice our religion, we were all tied up. We were so sick. Many people got sick because the Church authorities took away our religion, our lives. We people of costumbre would just sneak around the outside o...