![]()

1

A Case for the Prosecution

“I see you, Old Man.” “I see you, too.”

“Is everything well in the village?”

“It is well.”

“Is the lion still nearby?”

“Yes. But I am not afraid, for I still have my lantern.”

—Conversation with an African villager: 1971

Darkness had fallen. A cacophony of shrieks and sounds heralded the excitement of yet another of Africa’s nocturnal awakenings. There was an urgent knocking on the screen door.

Inside, shrieks of laughter and the tinkling of cocktail glasses dulled even the relentless shrill of the cicada beetles. Mother and Father were enjoying sundowners with friends inside a screened ‘boma’ which served as our family’s living quarters. The knocking went unheard.

“Memsahib … Memsahib!” whispered the African askari, opening the screen door just enough to poke his head through. As a night guard, it would have been impolite for him to have intruded any further into the sanctuary of his master’s home. He was an old man with white hair and a face deeply etched by years of toil in the African bush; quite how many years, he was incapable of remembering. He looked deeply concerned.

“What is it?” asked Mother, momentarily distracted from her guests. She was standing close to the door and was worried by the grave look on the old man’s face.

“Watoto na maliza. Simba iko karibu sana!” rasped the askari, his voice raised in alarm. He was sweating profusely in the sweltering, heavy night air; his luminous eyeballs contrasting starkly with the moist sheen of his black skin. He wore an oversized khaki tunic and a matching pair of oversized shorts which ballooned over his spindly legs like the sails of an Arab dhow. In his sinewy hand he clutched a wooden club, or knobkerrie. It was a far cry from the Lee Enfield he had carried while proudly serving with the King’s African Rifles.

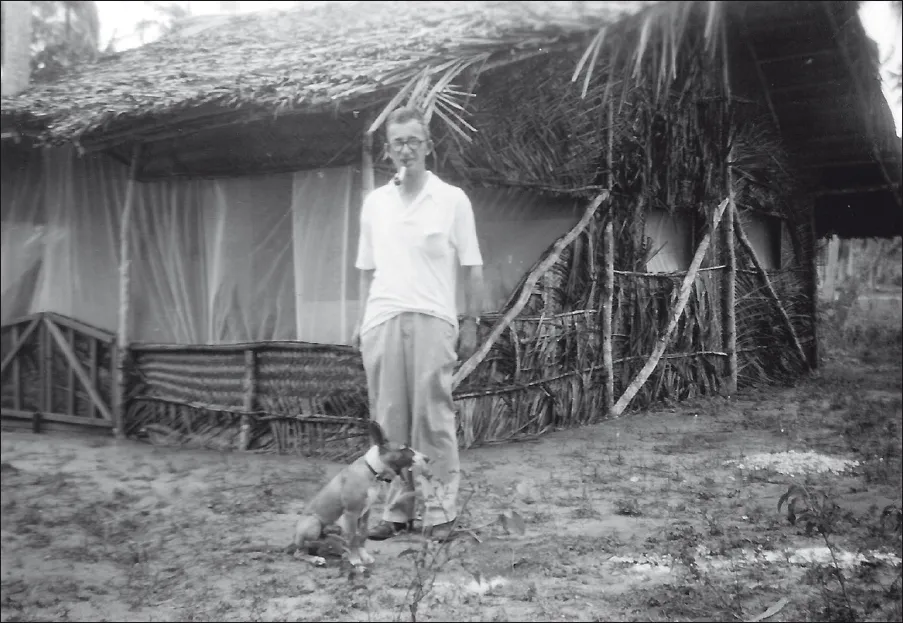

Our first house: a thatched roof with walls of mosquito netting. (Tim Bax)

“What’s worrying the poor man?” asked Father, suddenly aware of the askari’s presence.

“He says the children are crying,” replied Mother, hastening to the door. “He says there’s a lion nearby.”

As if to punctuate her remark, the unmistakable deep-throated grunt of a black-maned lion reverberated menacingly through the still, black night. The surrounding bush fell immediately into a deep and uneasy silence. A startled hush enveloped the boma. Even the cicada beetles ceased their chorus, as if silenced by some mystical stroke of a conductor’s baton.

Tonight as with every night, the askari had been guarding the open-sided sleeping boma which I shared with my two sisters. It was nestled under the canopy of a large acacia tree a few hundred feet from the living quarters where Mother and Father were now entertaining. Except for a waist high screen of thatch that surrounded the boma, burgeoning white mosquito nets hanging from a makeshift roof of palm fronds provided the only protection between us and the surrounding bush.

“Well, tell him to chase the damn thing off.” Father was helping himself to another whisky. “We can’t have it upsetting the children.”

Mother quickly reached for one of the smoking kerosene lanterns that were providing the only light and stepped outside. The dutiful askari followed close behind.

“I’ll be back as soon as I’ve settled the kids.” Clutching her cocktail, she moved quickly into the stillness of the dark, moonless night.

The party resumed.

So did the persistent call of the cicadas.

It was another routine night in the decadence of Colonial East Africa.

Recounting that and other stories of our early childhood, Mother seemed entirely unrepentant. Our family comprising Mother, my twin sister Janet, older sister Shelagh and me had just finished a lazy Sunday morning breakfast in the regulated security of our second floor apartment in Toronto, Canada. Outside, the swirling, wind-driven snow of another bleak Canadian winter had collected in thick drifts on the window ledges. A thin icy layer of condensation had formed on the inside of the windows. The cold, blustery weather seemed far removed from the tropical warmth of Africa which we had left two years before.

“Mother!” exclaimed Janet indignantly. “It’s jolly lucky we weren’t all dragged to our death by some ferocious wild animal. It’s very irresponsible of you to have left us sleeping miles out in the bloody bush while you and Daddy stayed up partying all night!”

“Now don’t exaggerate, dear. You children were only a short way off and Daddy had hired an askari to protect you. Besides, we didn’t stay away from you all night.”

“Fat use the askari would have been with just a knobkerrie against a whole bloody pride of lions!” Janet persisted. “How we all managed to survive I’ll never know.”

“Well, your father always had a gun with him. He would have shot anything that came too close,” sighed Mother, becoming a little exasperated.

“Oh, that’s great! Then we would really have been in mortal danger, Daddy blasting a bloody great elephant gun in our direction with just a mosquito net for us to hide behind.”

“Now stop it, dear. Your father was a highly-decorated soldier who knew how to handle guns.”

Janet was not to be stopped. “Mother, there’s a big difference between shooting at some Germans, and staggering out into the African bush after a few whiskies at night shooting at a pride of hungry lions walking between our beds. I’m appalled!”

“Janet, I do wish you would stop exaggerating.” Mother was unsuccessfully trying to escape further persecution by engrossing herself in the Sunday crossword.

“Well, I think that at the very least, you and Daddy could have waited until you had a proper roof over your heads before starting a family.”

Janet had sanctimoniously curled herself up on the couch surrounded by great wads of tissues into which she was relentlessly blowing an extremely red, snotty nose.

Outside the snow had turned to wind-driven sleet which beat a rhythmic tattoo against the icy window.

East Africa

“I became terribly bored. I wasn’t even allowed to make myself tea.

There was a servant to make it, another to serve it.”

“What did you do?”

“I started drinking my husband’s gin.”

—Tanganyika settler’s wife: 1955

Mother and Father arrived in East Africa in 1947. With them was my sister, Shelagh, who was a year old. Father had been sent by the British Colonial Office after the war to take part in a scheme to grow groundnuts near the palm-fringed port of Dar-es-Salaam, the capital city of the British-controlled colony of Tanganyika. The scheme was to bring untold wealth and prosperity to the impoverished region.

Before its official launch the scheme had to be given a name, one that would capture the spirit and boldness of such an imaginative enterprise. After much deliberation a name was finally chosen. It was to be called ‘The Groundnut Scheme’. (They were British, after all.)

Finding volunteers to participate in the scheme wasn’t a problem. There were thousands of recently demobilized servicemen anxious to leave the gloom of Britain’s post war economy for the excitement and glamour of Britain’s East African colonies. Among them was my father, a decorated and flamboyant armored corps cavalry officer who had demobilized from the British Army with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. Commissioned in the field, he was the recipient of the Military Medal (MM) for bravery and had been invested as a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for his exploits on the battlefield. But he knew nothing about farming, much less of growing groundnuts. Neither apparently did anyone else.

The torrential rains which lash the coastal plains of East Africa through the summer were a phenomenon that had escaped the attention of the Foreign Office. It was only when the squadrons of heavy plant machinery shipped from England began getting bogged down in a seething quagmire of mud that alarm bells began to ring. By then it was too late.

When the rains subsided, the scorching tropical sun baked the ground to the consistency of dried concrete. It could barely be penetrated by a jack-hammer much less the struggling groundnut seedlings trapped below.

The Groundnut Scheme’s collapse was almost as dramatic as its grandiose beginning. Its only legacy was a large number of families from Britain who suddenly found themselves in East Africa devoid of a living; Father amongst them. Undaunted, they did what the British have always done when faced with such adversity—they flocked to the club for a pink gin.

Father at least had the wisdom to abandon the sinking ship before the official pronouncement from London to “scuttle the bilges.” By that time the ship had already sunk. The Foreign Office had always been slow in admitting its mistakes; it was slower still in making public pronouncements about them.

Into this crucible of doubt and confusion was born my twin sister, Janet. I followed rather belatedly some 20 minutes later. It was 1949.

My African journey had just begun.

Even after the failure of the Groundnut Scheme, large numbers of families continued to pour off the ships at Dar-es-Salaam. They all needed a place to live so Father started building houses. But it wasn’t quite like a duck taking to water. He knew little about house construction. In fact, he knew nothing.

But the devil is in the detail, and Father proved nimble at avoiding the many stumbling blocks that lay strewn along his way. Where there wasn’t a European way to circumvent a building problem, there was always the uncomplicated African way. Kiln-dried bricks were in short supply and came with a price tag bigger than Father could afford. But the clay earth that had so effectively torpedoed the Groundnut Scheme was like gold dust to a builder. Father recruited a small army of unskilled laborers to form clay bricks in wooden handmade molds that were left to bake under the hot tropical sun. He leased a large tract of land close to the tranquil Indian Ocean, cleared it, and began building.

Constructing one of Father’s ‘domino houses’. (Tim Bax)

Father’s office consisted of an old canvas chair and makeshift folding table placed under the shade of a large umbrella tree. Upon it each morning he would arrange his rough building plans, a thermos of tea laced with whisky, and a large tin of Erinmore flake pipe tobacco. It was from here that he directed building operations, like a film director overseeing a cast of unrehearsed amateurs. He was never without his old meerschaum pipe. He said it kept the sand flies away.

Slowly, very slowly, the houses reached completion. Soon row upon row of little rectangular brick and stucco houses sprang from the ground looking like neatly placed dominoes.

There was no shortage of families wanting to take occupancy. Business in the colonies was as likely to be concluded over a handshake and a pink gin in the cordial atmosphere of the Dar Club as in a banker’s office. To Father, the passing of cheques was a bothersome and irksome formality which seldom got in the way of allowing families to take ownership of a new home. The result was that his cash reserves began receding as quickly as the outgoing tide.

But there was always the hope of a better tomorrow. It was the glorious days of colonial clubs and gymkhanas, of pink gins and stengahs, of bored memsahibs and lavish cocktail parties and of servants … legions of them. For the newly arrived housewife from England there were servants to take care of her every need. One only needed to clap one’s hands and shout “Boy!” to have a splendidly-attired native discreetly appear like a genie from a lantern. A strict ‘pecking order’ ensured that each servant knew his or her place within the hierarchy of the household.

At the top was the ‘houseboy’ whose function was to all but manage the home; sometimes he did that as well. Below him were cook boys, laundry boys (or dhobis), garden boys, night guards and the ubiquitous ‘ayah’, or nanny. No household with children was ever without an ayah.

For want of anything else to do, the ‘memsahib’ would usually spend her day at the gymkhana club playing tennis, or golf, or ‘someth...