eBook - ePub

Am I Dreaming?

The Science of Altered States, from Psychedelics to Virtual Reality and Beyond

James Kingsland

This is a test

Partager le livre

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Am I Dreaming?

The Science of Altered States, from Psychedelics to Virtual Reality and Beyond

James Kingsland

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

When a computer goes wrong, we are told to turn it off and on again. In Am I Dreaming?, science journalist James Kingsland reveals how the human brain is remarkably similar. By rebooting our hard-wired patterns of thinking - through so-called 'altered states of consciousness' - we can gain new perspectives into ourselves and the world around us.From shamans in Peru to tech workers in Silicon Valley, Kingsland provides a fascinating tour through lucid dreams, mindfulness, hypnotic trances, virtual reality and drug-induced hallucinations. An eye-opening insight into perception and consciousness, this is also a provocative argument for how altered states can significantly boost our mental health.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Am I Dreaming? est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Am I Dreaming? par James Kingsland en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Biological Sciences et Neuroscience. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

Biological SciencesSous-sujet

Neuroscience1

Magical Thinking

It seems that as humans, even when all our immediate biological needs have been met, there remains a hunger for meaning. We long for a greater sense of connectedness with nature and the universe, some kind of reassurance that each of us plays a part in a grand narrative that will continue long after we have left the stage. Throughout recorded history, altered states of consciousness – whether they are brought on by drugs, music, drumming, dance, or exacting spiritual disciplines such as meditation, isolation and fasting – have satisfied this profound hunger, a yearning that has nothing to do with the basic biological drives for food, shelter, social status or sex. What other animal seeks out meaning?

This search for meaning is not an idle pursuit. To discover that you play a minor role in a cosmic drama that transcends your everyday self can be hugely beneficial for mental well-being. The impressive clinical effects of psychedelics recorded in studies over the past few years appear to be directly related to their ability to provoke meaningful, even spiritual experiences. The self-transcendent insights they afford have proved particularly helpful for people forced to confront their own mortality. A few years ago, when Stephen Ross and his colleagues at New York University School of Medicine gave a single dose of psilocybin (found in magic mushrooms and truffles) to twenty-nine people struggling to cope with a cancer diagnosis, the psychedelic significantly improved their quality of life and brought immediate and substantial relief from symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Their study employed a ‘crossover’ design: patients either took psilocybin in a first session followed by a placebo seven weeks later, or vice versa. Each was also given conventional psychotherapy. Six-and-a-half months after the treatment, between 60 and 80 per cent were still reporting clinically significant improvements in symptoms of anxiety and depression compared with the start of the trial. Crucially, this therapeutic effect seemed to be mediated by the spiritual insights they had while on psilocybin. Some 70 per cent of all the patients reported that, even though their trip was emotionally challenging, they rated it as among the top five most personally meaningful experiences of their entire lives.1

One of the patients, a fifty-one-year-old woman called Erin, who had been knocked sideways by the news she only had a 50:50 chance of being alive in five years’ time as a result of ovarian cancer, described a vision that gave her a vital insight.2 Under the influence of psilocybin, she saw a round dinner table:

… and at the table was cancer, but it was supposed to be at the table. It isn’t this bad, separate thing; it’s something that’s part of everything, and that everything is part of everything. And that’s really beautiful. It was just a sort of acceptance of the human experience because it’s all supposed to be this way.

She realized that cancer and death must have a place at the table: they are as integral to the natural order as life itself. And with that realization came the peace of acceptance.

Similarly, in a trial led by Robin Carhart-Harris at Imperial College London, reported in The Lancet Psychiatry in 2016, twelve patients with treatment-resistant major depression experienced significant, sustained reductions in their symptoms after taking just two doses of psilocybin one week apart alongside conventional psychotherapy. Again, these clinical improvements correlated with ratings of how insightful or mystical they judged the drug experience to be.3–5

In the modern world, doctors have assumed the healing role once played by priests and shamans, but theirs is a mostly biological conception of illness that can overlook patients’ spiritual needs. Their pills are not designed to restore a sense of meaning, connectedness or purpose to people’s lives. Prozac and Valium don’t work by offering insights into one’s problems but by damping down their emotional impact, which goes a long way towards explaining why conventional antidepressants and anti-anxiety drugs like these must be taken continually for their effects to be sustained, whereas research to date suggests that just one or two doses of a psychedelic can be life-changing. Also worth bearing in mind is the fact that taking conventional antidepressant and anti-anxiety drugs is often associated with side effects such as drowsiness and sexual dysfunction, and can lead to dependence: when patients stop taking them there may be unpleasant withdrawal effects, including a sharp rebound in their original symptoms.

Age-old techniques for provoking altered states of consciousness, such as meditation, sleep deprivation, trance and hallucinogens, are well known for their ability to precipitate spiritual and emotional breakthroughs but, as I would be the first to acknowledge, they are inherently risky for some people. There is a delicate balance to be struck between laying oneself wide open to spiritually meaningful experiences and triggering a ‘psychotic episode’ in which one can lose touch with reality for days, weeks or longer, with hallucinations and possibly delusions of persecution or grandeur. Research suggests that consciousness-warping chemicals and practices allow us to dissolve rigid patterns of thought and behaviour, including drug addiction and depression, like shrugging off old clothes that have grown worn and uncomfortably tight over the years. In the process, however, they expose the naked psyche to the cold blast of painful memories and emotions. And there can be no guarantee that the new clothes the mind finds to put on will fit any better than the old ones. For a few unlucky people, in particular those vulnerable to psychosis, the fit may be more uncomfortable.

All the altered states of consciousness I explore within these pages involve what psychologists call ‘dissociation’ – a temporary disconnection from everyday reality. But for the small percentage of people who have experienced psychosis or who have a family history of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, these states run the risk of severing this link for longer periods, perhaps permanently. Psychedelic researchers recruiting volunteers for their studies will reject applicants if they fall into these categories, as will many meditation and ayahuasca retreat centres, as I learned to my disappointment. For everyone else, a supportive environment – a calm, protected space with compassionate, experienced individuals on hand – is essential to maximize the benefits and minimize the risks associated with these extraordinary experiences, in particular allowing any difficult emotions and memories that come up to be processed safely. Just as importantly, the healing process doesn’t end when people return to ordinary consciousness. In the weeks and months that follow, the profound insights and revelations must somehow be integrated into everyday life, for example through a daily meditation practice, spending more time in nature, creative pursuits or voluntary work.

If you are wary of the idea of temporarily disengaging from reality, it’s worth remembering that this is what happens every night while you sleep. In the next chapter, I explore the idea that dreaming sleep streamlines our models of the waking world, pruning redundant synapses that have accumulated during the day’s learning experiences and helping our brains to function more efficiently. In order to do this, they must switch off almost all sensory inputs and motor outputs and suspend the mind’s reality-checking faculties.

No wonder dreams, like the delusions of psychosis, are so very convincing. But if this nocturnal housework isn’t carried out properly every night, the nervous system becomes increasingly cluttered with unnecessary connections. Like an ageing desktop computer, this means it works less efficiently, disrupting not just cognition but also homeostasis – the maintenance of a stable internal environment including essential tasks such as regulating temperature, pH and blood sugar levels. Not getting enough sleep (at least seven hours a night) is strongly associated with an increased risk of poor mental and physical health, including depression, suicidal thoughts, cancer, diabetes, heart disease and Alzheimer’s.6,7

The effects of sleep deprivation on homeostasis are particularly striking. While research ethics committees would not allow such an experiment to be performed on humans, rats deprived of sleep for more than eleven days die as a result of a complete breakdown in their ability to maintain a stable body temperature.8

One of the take-home messages of this book is that you can’t reap the restorative benefits of sleep, or any other altered state of consciousness, without temporarily disconnecting from the reality checks that your senses and rational mind normally provide. According to the leading theory of how we develop and maintain our cognitive models of the world, known as ‘prediction error processing’, the streamlining that underpins the restorative powers of altered states can only occur after entire levels of the brain’s processing hierarchy have been taken offline.

The trouble starts when people mistake what they dreamed, or the visions they saw, for reality. Psychiatrists call this ‘magical thinking’. Like many people, I have come to believe that science is our best friend for judging what is and is not real, so I get uncomfortable when some folk who have experienced altered states talk earnestly about supernatural phenomena such as astral projection – the ability to shed one’s physical body and wander the cosmos – past lives and spirit guides. Like the contents of a dream in the moments after awakening, these things can seem all too real. Not even scientists are immune to magical thinking. Shortly before I travelled to Peru, I interviewed a highly respected researcher who has investigated the potential clinical benefits of drinking ayahuasca and personally taken part in many ceremonies. The changes in his worldview apparently wrought by the medicine were startling:

Everything has consciousness. Plants, animals, rocks, you name it. The issue is how compatible is their awareness with our awareness. And in the case of plants they don’t think. Their awareness is very, very different from ours. But when we reach out to the plant world and acknowledge that they feel, that they have awareness, plants will create a kind of hybrid awareness. These are the divas that folks in the shamanic realm will talk about.

Ayahuasca has created a bridge to us, and this bridge is the spirit you will encounter in your ceremony. She is an absolute hard ally in this process. She will help you. If you develop a relationship with her and trust her she will take you exactly where she understands you need to go to heal, and that will be totally different from where your mind will think to go.

This well-meaning scientist’s words only served to heighten my reservations about drinking ayahuasca. His conception of the medicine as opening up a channel of communication with plant spirit guides is in accord with what the shamans will tell you, and is a useful metaphor for how the healing works, but many regular users come to believe in a literal Mother Ayahuasca. Who knows? There may be something to their insight of a hidden realm of plant and animal spirits willing and able to help out with our problems. Personally I prefer to remain sceptical about such things.

The paradox of altered states of consciousness is that they restore openness, flexibility and meaning to our lives by temporarily messing with our reality-checking faculties. What fascinates me is that in the process, they reveal so much about how the brain strives to make sense of the world. The more we have learned about altered states, the more light they have shone on ordinary waking consciousness, exposing the hidden hand of belief, expectation and brain chemistry in everything we experience.

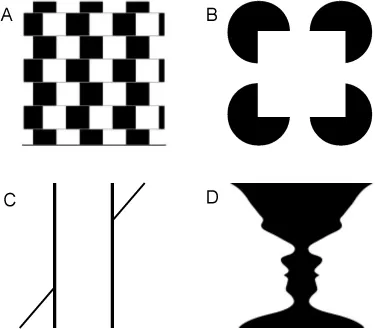

Optical illusions demonstrate that, as the British psychologist Richard Gregory observed in 1980, perceptions are like scientific hypotheses.9 They are our best guesses based on the limited evidence available to us. Because sensory stimuli are inherently ambiguous, the brain must weigh the rough-and-ready ‘rules of thumb’ it has learned (its expectations based on past experience) against the likelihood that the available sense data is reliable. The result of this subconscious calculation is conscious perception. The classic optical illusions shown in Figure 1 are caused when the brain invests too much confidence in predictions based on its rules of thumb, giving insufficient credence to raw sensory information. In the Café Wall (A), Kanisza Square (B) and Poggendorff (C) illusions, the context fools the brain into applying rules that lead us to see, respectively, parallel lines as converging or diverging; a complete square; and two segments of a diagonal line as offset rather than aligned. In the Rubin’s Vase illusion (D) the brain vacillates between two alternative interpretations: a vase or two faces.

Figure 1: These classic illusions reveal how the brain can slip up when it applies ‘rules of thumb’ to ambiguous sensory data

Even if we are perceiving something for the very first time, the brain will always reach for what it already knows. To a metaphorical ‘fish out of water’ – a creature in an unfamiliar environment – a tree might look like seaweed waving in an ocean current until, through the interplay of its predictions and sensory prediction errors, the fish has updated its model to predict something more rigidly tree-like.

Clearly there’s more to conscious perception than a stream of predictions flowing in one direction and a stream of prediction errors coming back in the other. Without some way to filter or vet the barrage of prediction errors, the mind would be quickly overwhelmed or easily misled. What altered states reveal is the importance of the brain’s chemical tuning systems. Karl Friston, a neuroscientist based at University College London who helped pioneer the theory of prediction error processing, told me how these might work. For a start, he said, our brains don’t need to pay any attention to sense data that exactly match their predictions:

The breaking news is the surprising stuff – the bits you didn’t predict. But you’ve still got to select which channel to tune into. Do you go for Sky News, BBC News or Fake News? You have to tune in and boost those prediction errors you think are going to have reliable, precise information, and ignore or turn down the volume of Fake News.

This is the role of attention: bringing the mind’s processing...