eBook - ePub

The Book of Knowing

Know How You Think, Change How You Feel

Gwendoline Smith

This is a test

Partager le livre

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

The Book of Knowing

Know How You Think, Change How You Feel

Gwendoline Smith

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Written in an accessible and humorous style, this book teaches you to know what's going on in your mind and how to get your feelings under control. It'll help you adapt and feel better about your place in the world.Psychologist Gwendoline Smith uses her broad scientific knowledge and experience to explain in clear and simple language what's happening when you are feeling overwhelmed, anxious and confused.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que The Book of Knowing est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à The Book of Knowing par Gwendoline Smith en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Persönliche Entwicklung et Persönlichkeitsentwicklung. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sous-sujet

PersönlichkeitsentwicklungCHAPTER ONE

I never quite made it to the Philosophy Department at university. A psychology major allowed me more time to pursue my other passion—playing eight-ball.

In recent years, since studying cognitive behavioural psychology, I have become quite keen on a guy called Socrates. I would have to say he is my favourite philosopher. He was saying really interesting stuff way back in circa 470 bc. (Yes, long before the internet.)

He was committed to the concept of reason. He believed that, properly cultivated, reason can and should be the all-controlling factor in life. Not surprisingly, being such a pioneering and brilliant mind, he was sentenced to death by poisoning, because of his refusal to acknowledge the gods recognised by the state and for his supposed ‘corruption of youth’—I would have referred to it as enlightenment!

Socrates was probably the most extraordinary mind of the time. He was responsible for the conception of the Socratic dialogue, his method of teaching. He never wanted to ‘teach at’ his students. That would be to instil doctrine. His pet hate.

Instead, he wanted to guide his students to discover their answers for themselves. He did this through a method called ‘Socratic questioning’ which set out to uncover assumptions and unexamined beliefs, and then to think about the implications of those beliefs—all this to really test whether the answers made sense.

This form of questioning became the backbone of law studies (and Suits script writers) and was later picked up by the world of psychotherapy, including cognitive behavioural therapy, in the 1960s—which is how I became interested in the technique.

As prescribed by Socratic dialogue, I focus on the ‘When?’, ‘What?’, ‘How?’ and ‘Where?’ questions in my clinical work. I choose not to delve into the ‘Why?’ question because in my experience it often leads down a path that goes both everywhere and nowhere:

The key message here is that you need to, and can, learn to adapt. On the evolution of species, Charles Darwin is often described as saying, ‘Only the fittest survive.’ What he was actually saying was, ‘The most adaptive survive.’

Look at cockroaches. They have been around for 320 million years—they watched the dinosaurs come and go. They are still with us today, and apparently resistant to every new insect spray on the market. Now that’s adaptive!

CHAPTER TWO

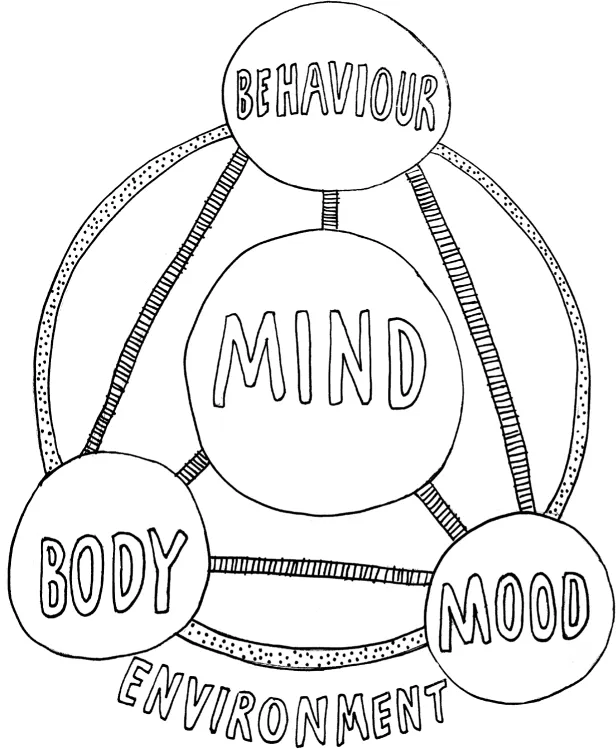

When I’m teaching I like to start off with the diagram opposite. This is a very standard template that explains the basis of cognitive behavioural therapy and how it all works. It is simple and in its simplicity lies Aaron Beck’s genius. I describe it this way—I hope Dr Beck would approve.

The first thing to remember is that our heads are attached to our shoulders. Not only that, but the brain is in charge of everything. It’s not called the ‘headquarters’ for nothing.

All of our physical sensations (body), everything we do (behaviour), everything we feel (mood) and our thinking (mind) are all inextricably linked to the brain. And all of these interact with the world around us (environment).

We could say, ‘I am a brain,’ but humans prefer to say, ‘I have a brain,’ hanging on to the belief that the ‘I’ is the self, and the self is a separate entity. This separate entity is where the soul supposedly lives—though that debate would require another book.

BODY

This is our physiology, everything to do with the body. Everything we can see: legs, hands, toes, breasts, teeth, etc. Then there is everything that we can’t see: hormones, neurotransmitters, chromosomes, biochemicals, DNA and so on. All of our physiology is at our fingertips, and yet there is so much we don’t know about it.

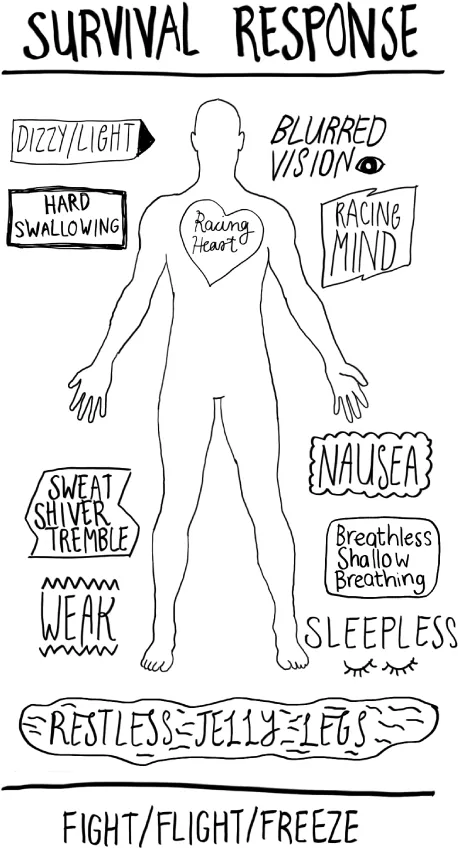

The illustration opposite shows how the body responds when under alert, or the ‘survival response’. When faced with a perceived threat, your body prepares you to either go on attack (fight), run away (flight) or try to make yourself invisible (freeze). This is the same response that occurs when humans describe feeling anxious.

Some of the physical reactions that can occur as part of your body’s ‘survival response’—preparing you to fight, flee or freeze.

If you become unwell, for instance with the flu, you experience all the physical symptoms associated with it: sneezing, coughing, nose running, head blocked (body). In response to this, you probably go to bed and rug up (behaviour).

Then, lying in bed and not being able to get out and do the things you enjoy, you start to feel miserable (mood). Sometimes, while lying there, you also start to think about what you’re missing out on (FOMO) and how none of your friends have come to visit you. Your emotions can be impacted further, making you feel even more miserable (mood).

Hopefully you are starting to see what I mean about everything being inextricably linked.

BEHAVIOUR

Let’s use exercise as an example. Let’s say you like to go for a run or go to the gym several times a week. One day, while out running, you sprain your ankle and have to have it strapped up (body). This means no exercise for some time. You may start to worry that you are going to get fat and out of condition (mind). These thoughts can then create discomfort and/or anxiety (mood).

When you exercise, your body releases biochemicals called endorphins, which have a positive effect on your feelings. Because you are not running, you are not getting those endorphins or any of the other physical benefits of exercise (body), and you worry that you are going to turn into a fat slob (mood).

MOOD

In the developed world we are becoming increasingly obsessed with mood. We have lists of all sorts of possible mood disorders—anxiety, depression, bipolar, to name but a few. Pills to take you up, to take you down, to level you out, to take the edge off. Name it, there is undoubtedly a pill for it.

This is not a new thing. Most cultures have long had drugs to help people alter their state of consciousness and, in turn, their emotions: these include opium, peyote, marijuana, LSD, alcohol, tobacco and many more. It is a very, very long and ancient list. However . . .

Making billions out of the manufacturing of pharmaceuticals and criminalising what comes out of Mother Nature’s garden is new.

The other manifestation of our fascination with all things emotional is the arts: love poetry, melancholic poetry, music about love and loss, more loss and more love, novels, painting, comedy, dance. The wonderful world of the arts.

I love all of these aspects of life, but the scientific reality is that emotions are about neurotransmitters and hormones...