eBook - ePub

Histories of the Unexpected: The Tudors

Sam Willis, James Daybell

This is a test

Partager le livre

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Histories of the Unexpected: The Tudors

Sam Willis, James Daybell

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Histories of the Unexpected not only presents a new way of thinking about the past, but also reveals the world around us as never before.Traditionally, the Tudors have been understood in a straightforward way but the period really comes alive if you take an unexpected approach to its history. Yes, Tudor monarchs, exploration and religion have a fascinating history... but so too does cannibalism, shrinking, bells, hats, mirrors, monsters, faces, letter-writing and accidents!Each of these subjects is equally fascinating in its own right, and each sheds new light on the traditional subjects and themes that we think we know so well.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Histories of the Unexpected: The Tudors est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Histories of the Unexpected: The Tudors par Sam Willis, James Daybell en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Geschichte et Britische Geschichte. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

GeschichteSous-sujet

Britische Geschichte• 1 •

THE CHAIR

A woodcut of a cucking stool originally printed in A Strange and Wonderful Relation of the Old Woman Who Was Drowned at Ratcliff-Highway (London, no date)

In the Tudor world, chairs were used to control the public…

DUCKING AND CUCKING

In the Tudor world, chairs were used to control the public, and the ducking stool was the most extreme example. Used to punish a variety of offences – including scolding, illegitimacy, prostitution and witchcraft – the ducking stool was built like a wooden see-saw, with a chair at one end of the ‘lever’. The accused would be tied to this chair and plunged into water, usually by raising up the lever’s opposite end. According to Tudor legal commentators, the suspect was ‘to be ducked over the head and ears into the water’. The nature of this act of immersion depended on the nature of the crime – it could be a short sharp shock for minor offences, or continually repeated throughout the day in more severe cases. On occasion, the punishment was fatal.

Closely related was the cucking stool, which, far more simply, was used for ritual humiliation: the individual was forced to sit in the chair in a public place as an act of penance, in full view of passers-by. Designed to shame, it worked in much the same way as other forms of rough justice.

In the Tudor period, ducking and cucking stools were used to punish troublesome and angry women – commonly termed ‘scolds’ – who had caused social disorder. While they were also the fate of brawling men, and male traders who cheated the public by selling short measures or adulterated food, over the course of the sixteenth century such stools became increasingly associated with the abuse of women. As with the scold’s bridle, metal headgear which included a plate that fitted in the mouth to restrain a prattling tongue, they were used to control what was deemed wayward female behaviour.

Rough justice

Rough justice in the Tudor world was the heavy-handed, harsh punishments that were meted out instead of fining or imprisonment. Many offenders were wheeled around in an open wooden cart; others were placed in a pillory, a large hinged wooden board with holes for securing the head and hands, or stocks, which restrained the feet. These were erected in public spaces, and passers-by could insult, spit at, taunt or even hurl fruit at the imprisoned occupants.

WITCHES

Ducking stools were also used as a test for women accused of witchcraft : those who rose to the surface when immersed were deemed to be guilty, the Devil conspiring in saving them; while those who sank were drowned but with their innocence intact.

Another coercive type of chair was the ‘interrogation stool’, on which those accused of witchcraft were forced to sit as they were questioned about their supposed crimes. We know of the existence of such stools from Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida (Act II, Scene i), when Ajax issues the insult ‘Thou stool for a witch!’

An example of a witch’s interrogation stool survives in the cottage of Shakespeare’s wife, Anne Hathaway, in the Warwick-shire village of Shottery. Carved from oak and ash and with four legs, the most fascinating aspect of the stool is the five sets of concentric circles carved into the seat. They resemble the ring patterns commonly found on wooden mantelpieces, beams and door lintels of Tudor properties; known as ‘witch-marks’, these were believed to ward off evil spirits.

Witch-mark found on beam in a sixteenth-century house in Herefordshire, UK

The presence of such markings on an interrogation stool was supposed to neutralize the occult power of the witch when she was forced to sit, often tied to the stool, for interminable periods of time. While it is difficult to reconstruct what that experience was like for women accused of witchcraft, the interrogation stool as an object does conjure up something of the atmosphere of the courtroom, in which the accused could be confronted by hostile audiences and were stripped and searched for another kind of witch’s marks (also known as ‘devil’s marks’), such as an odd-looking birthmark or an extra nipple. In 1579, a court in Southampton ordered a dozen ‘honest matrons’ to strip-search one widow Walker and check for ‘eny bludie marke on hir bodie which is a common token to know all witches by’.

THRONES

At the Tudor court, another chair, the royal throne, was used for social control in a different way. Ornately and richly decorated and raised on a plinth, the throne emanated power and grandeur. It singled out the monarch above all others, and it was also used to regulate access to them.

Several of Henry VIII’s thrones survive at Hampton Court and Dover Castle, and they appear rather less grand than one might expect. Both are relatively small carved wooden chairs, upholstered in red velvet and decorated with gold braiding. There is a sense that these particular examples were functional rather than fancy – they were everyday thrones for the king.

On an entirely different level, however, were Tudor coronation thrones. A set of detailed instructions for the preparations of Westminster Cathedral for the coronation of Mary I in 1553 gives a wonderful sense of the rich opulence of the royal throne that was at the centre of a very public ceremony.

The notes describe a scaffold with a throne set at the top of seven stairs. The throne itself was ‘in the midst’ of it, ‘a great white chair’ with two pillars topped with two gold lions and a gold fleur-de-lys. It was covered with a canopy of gold cloth and furnished with two cushions, one black velvet embroidered with gold, the other of tissue. Edward VI’s own coronation throne included the addition of two cushions ‘to help raise the small King’.

THE PRESENCE CHAMBER

The significant role of the throne continued long after the coronation ceremony. For Tudor courtiers, the ability to move from public areas to the more private spaces connected with the monarch was a sign of royal favour. Central to this procession of power was the presence chamber – the room where the monarch received visitors – and the key piece of furniture here was the throne and canopy (or ‘chair and cloth’ of state), upon which the monarch sat.

To be rescinded access to the monarch’s presence on his or her throne was to fall from political favour. And that fall could be hard. Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex – who was executed for treason in 1601 – was denied admission to Queen Elizabeth late in 1599 after he deserted his military command in Ireland. For Essex, the fact that he would no longer see the queen on her throne was a sign of ill things to come.

Robert Devereux (1565–1601)

The Earl of Essex was an English nobleman, military commander and royal favourite of Elizabeth I. He was put under house arrest in 1599 as a result of his poor military leadership in Ireland during the Nine Years’ War. Frozen out of the queen’s favour, Essex attempted to march on the court in order to try to capture the queen and seize power for himself and his supporters. The coup failed, and Essex was arrested, put on trial and beheaded.

Exactly who was allowed to approach the throne in the Tudor period was thus strictly controlled, so much so that in Elizabeth I’s reign one of her Gentleman Ushers of the Chamber, Simon Bowyer, was ordered by the queen to deny access to anyone without proper papers. He incurred the wrath of the Earl of Leicester on one occasion when he refused access to one of the earl’s known clients, yet the queen herself backed up Bowyer, emphasizing that she alone decided who had the privilege of time with her as monarch, seated on her throne.

• 2 •

MONSTERS

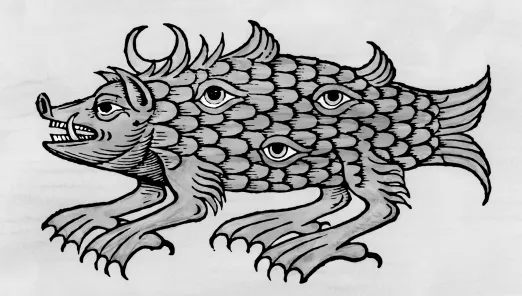

Woodcut of Argus sea monster in Monstrum in Oceano Germanica (‘Monsters of the North Sea’), from Olaus Magnus, 1537

The Tudors saw monsters as a message…

PHYSICAL DEFORMITY

The Tudors viewed monsters as messages or signs that explained the world around them, and they saw them in places we do not. One of those places was in humans and animals suffering from physical defects.

Such occurrences were widely known, and were reported in printed newsbooks and pamphlets of the period. Between 1552 and 1570, sixteen ‘monstrous’ births were recorded and no fewer than nineteen monstrous fish were put on display.

A particularly notable year for monstrous events was 1562, as recorded by the renowned English historian and antiquarian John Stow in his Annales of England (1592):

In March a Mare brought forth a foale with one body, and two heads, and as it were a long taile growing out betweene the two heads. Also a sow farrowed a pigge with foure legges like to the armes of a man child, with hands and fingers…

The foure and twentieth day of May, a man childe was borne at Chichester in Sussex, the head, armes, and legges whereof, were like an Anatomie, the breast and belly monstrous big from the navell, as it were a long string hanging: about the necke a great collar of flesh & skin growing like to the ruffe of a shirt or neckerchefe, comming uppe above the eares pleyting and folding.

Such monsters represented a disruption to the ‘great chain of being’ that delineated the social and celestial hierarchy in the Tudor world and cosmos. In this system, everything was supposed to be neatly ordered and in its proper place – from God and the angels in heaven to the monarch and patriarchs on earth. The ‘monsters’ so widely reported and sensationalized represented a break in tha...