![]()

CHAPTER 1

Store Layout

Understanding and Influencing How Shoppers Navigate Your Store

Consumers and marketers alike were shocked in the 1950s when journalist Vance Packard published The Hidden Persuaders, a book highly critical of the methods used to influence consumer behavior. In a chapter titled “Babes in Consumerland,” Packard describes how consumer researchers observed women shopping in supermarkets and used this information to devise ingenious ways to “manipulate” them. Some of the in-store observations Packard described seem extremely exaggerated, stereotypical, and—from today’s more focused perspective—almost comical:

Many of these women were in such a trance that they passed by neighbors and old friends without noticing or greeting them. Some had a sort of glassy stare. They were so entranced as they wandered about the store plucking things off shelves at random that they would bump into boxes without seeing them and did not even notice the camera although in some cases their face would pass within a foot and a half of the spot where the hidden camera was clicking away.1

Although today’s consumer researchers hardly consider shoppers to be “in a trace” or “hypnotized” when in a store, in-store observations have remained an invaluable tool for planning and optimizing stores. They are particularly useful for planning the layout of a store. In our case, we are primarily interested in the routes that shoppers (not only women but also men) take when they walk through a store (Figure 1.1).

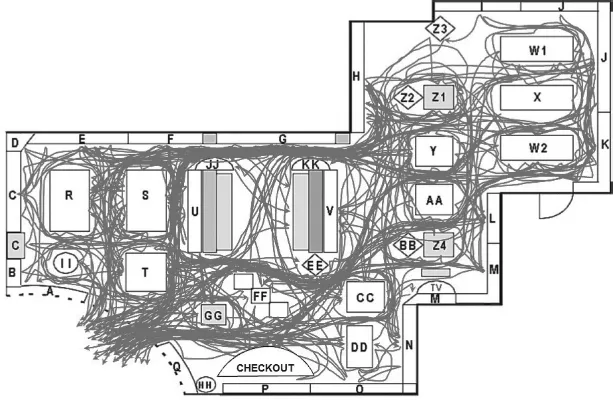

In Figure 1.2, you’ll see the (partial) results of an observational study we conducted in a bookstore.2 The lines represent the paths customers took through the store. The letters designate various product groups, such as cookbooks, travel books, stationery, and so on. While the path a single customer takes would not give you much insight, in the aggregate, typical patterns of movement do emerge. Obviously, traffic patterns in stores are not all alike. They vary depending on the layout of the store, its size, and the type of customers. For that reason, it makes good sense to conduct your own observations in a specific store to discover the problems and also the opportunities unique to that store. For example, in this bookstore there were comfortable benches that customers could use to sit on while browsing through the books that might have caught their interest.

As you can see, the results of this observation show that many shoppers use the reading zone (the area defined by the large benches in the middle of the store) as a shortcut to reach bookshelves located in the back of the store. In the process, they can disturb customers who are relaxing and reading books. Based on these results, we advised the management of this bookstore to slightly elevate the reading zone by adding a step to a reading platform. In this way readers could still easily access the benches, but at the same time, shoppers would be discouraged from using the reading area as a shortcut.

General Rules of Customer Traffic

While walking behavior will obviously vary from store to store, there are certain patterns that remain quite consistent. We have found them repeatedly in our studies, and they have also been reported by other marketers and consumer researchers. Let’s have a look at them. We’ll start right at the entrance of the store.

Transition Zone

“Caution! You are about to enter the no-spin zone,” conservative talk-show host Bill O’Reilly warns viewers at the beginning of his television show. In the same way, we want to caution retailers about the transition zone in a store. This term, coined by renowned retail anthropologist Paco Underhill, refers to that area of the store immediately beyond the entrance.3 Upon entry, customers need a short while to orient themselves in the new environment. They need to adjust to the many stimuli inside the store: the variation in lighting and temperature, the signs, the colors, and other shoppers, to mention just a few. This factor has important implications for designing the store.

The entrance is the only part of a store that every customer passes through (provided that there is only one entrance of course), and therefore many retailers and manufacturers consider it prime real estate. Nevertheless, quite the contrary is true: In the transition zone, shoppers’ information-processing capabilities are so occupied with adjusting to the environment and reaching their targeted destination in the store that they only pay minimal attention to the details that surround them in this transition environment. Let’s have a look at a lady entering an electronics store in Figure 1.3.

Do you see how this shopper looks straight ahead and doesn’t even notice the product display to her right? She also does not notice the shopping baskets on the floor to her left. She clearly needs a few more moments to adjust to the change in her environment. Sometimes we wonder what effect a sign proclaiming, “Everything free today!” has on consumers if that sign is placed right after the entrance into the transition zone. Unfortunately, we are still searching for a client willing to let us carry out that experiment in their store.

The transition zone isn’t a great place to display high-margin products or important information. This doesn’t mean, however, that retailers should neglect the area right after the entrance, as it is the place to make a great first impression on shoppers and—primarily in the case of mall stores where the entrance zone is clearly visible from outside—to attract passers-by into the store. The lush fruit and vegetable departments that some supermarkets put right at their entrance are an example of this technique.

Customers Walk Counterclockwise

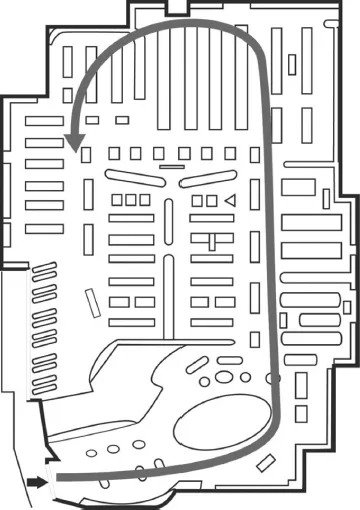

Have you ever noticed the direction you usually take after you have entered a store and successfully adjusted yourself to the new environment in the transition zone? While clearly not all customers are alike, many shoppers will walk counterclockwise through the store. This is a pattern that has been noticed by many consumer researchers.4 You can also see this pattern in one of our studies. Figure 1.4 shows the interior of a supermarket. The arrow indicates the typical walking pattern we observed in the store. Notice that the diagram is indicative of the pattern where very often customers walk counterclockwise after entering a store.

It has been argued that customers tend to walk counterclockwise or to the right because in many countries they drive on the right-hand side of the road.5 This explanation might be intuitively appealing, but it is probably wrong (e.g., consider England). We also did not observe this walking pattern in right-handed shoppers only. As research has shown, shoppers probably don’t have an innate or learned predisposition to walk to the right. On the contrary, it’s the store that makes them walk to the right because in most stores the entrance is on the right-hand side of the storefront. Unless customers walk to the checkout area right after entering the store (which is unlikely), they are more or less forced to walk first to the back of the store on the right and then eventually turn left. In fact, recent research suggests that customers might process information better if the entrance was to the left of the store rather than the right.6

Customers Avoid Narrow Aisles

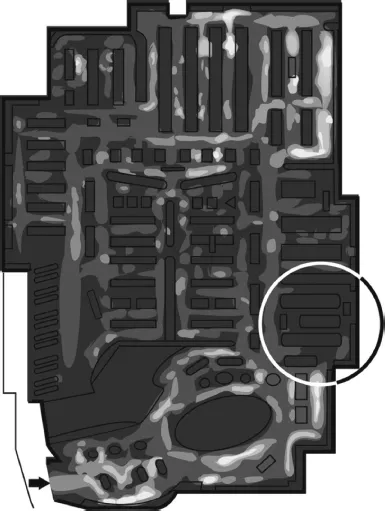

Stay with us in the same supermarket, and take a look at Figure 1.5. Relatively few shoppers walk in the areas that are shown in dark colors on the map, whereas the aisles that receive a lot of traffic are shown in white or light gray.

As you can see, relatively few customers enter the area that is circled because the aisles in this area are quite narrow compared with the aisles in the remainder of the store. In narrow aisles, customers feel that their personal space is invaded by other shoppers. For example, they may worry that another shopper will bump into them—for this reason, this phenomenon is called “butt-brush effect”7—or pass at an uncomfortably close distance. It should be noted, however, that this is not a universal occurrence. In cultures such as the United States or the United Kingdom, people maintain a relatively large social distance, whereas in other cultures (e.g., Arab or many Latin American countries), people will stand considerably closer to each other.8 Consequently, aisle width is less of an issue in these countries. In the United States, on the other hand, it is essential for retailers to plan aisles t...