![]()

What is Empiricism?

Knowledge and Belief

I’m sitting at my computer, after a long day, beginning the first few pages of this book, when without any warning a huge, leathery hippopotamus walks into the room.

Now I’m confident that I’m awake. Everything I see, hear, smell, touch and taste is real, this time. Knowing about the world through the senses is the most primitive sort of knowledge there is. I couldn’t function without it. But is it possible that I am mistaken, just as I was about the hippopotamus? How certain can I be about my perceptions of trees, jamjars and that cup of cold tea?

Most people assume that the world is pretty much as it appears to them. They believe a cat exists when they see it cross the road. But philosophers are, notoriously, more demanding. They say that beliefs are plentiful, cheap and easy, but true knowledge is more limited, and much harder to justify. This is why philosophers normally begin by separating knowledge from belief.

That’s enough to convert my beliefs into knowledge. But there is always a slight possibility that I am wrong. The world might not be as I believe it to be. Problems like these worry philosophers called “empiricists”, because they think that private sensory experiences are virtually all we’ve got, and that they’re the primary source of all human knowledge.

Inside and Outside

One thing we do know is that our senses sometimes mislead us. White walls can appear yellow in strong sunlight. Surgeons can stimulate my brain so that I “see” a patch of red that isn’t there. I can have hippopotamus dreams, and so on. My sense experiences are at least sometimes created by my mind – or somehow in my mind. These comparatively rare “mistakes” have led many philosophers to insist that all my perceptions are “mediated”.

But I don’t. What I see is a wonderful illusion created by my mind. Of course, I am totally unaware of that fact because my perceptions seem so natural, automatic and rapid. Psychologists tell me that what I actually see is a kind of internal picture, and they devise all sorts of tests and puzzles to prove it.

Originals and Copies

They say that the trees provide me with a “tree sensation” in my mind, and it’s that which I see, not the trees themselves. If that is true, then all I ever see are “copies” of those trees, which I assume are very similar in appearance to the originals.

But, if I think about this even harder, then I realize I have no way of telling how accurate these copies are, because I cannot bypass my mind to take another “closer look” at the originals.

Perhaps the original trees are nothing like the cerebral “copies” at all, or worse still, don’t even exist!

The more I think about perception, the weirder it becomes, and the more I realise that I must be trapped in my own private world of perceptions that may tell me nothing about what is “out there”.

Questions Lead to Uncertainty

This kind of unnerving conclusion is typical of philosophy. You ask simple questions which lead to unsettling bizarre answers.

If there isn’t, how can empiricist philosophers claim that all human knowledge comes from experience? If no one can ever be sure where “experiences” come from in the first place, how reliable are they?

To Begin at the Beginning

Empiricist philosophy is relatively new. Philosophy as such began very differently, with some ancient Greeks called “Pre-Socratic” philosophers who emphasized the differences between appearance and reality. They said that what we see tells us very little about what is real. True knowledge can only come from thinking, not looking. The first truly systematic philosopher, Plato (427–347 B.C.E.), agreed that empirical or sense knowledge is inferior because it is subjective and always changing.

Plato turned to mathematics instead. Unlike my trees, numbers are abstract, immune from physical change, the same for everyone, and have a permanence, certainty and objectivity that empirical knowledge lacks. Plato believed that real knowledge had to be like mathematics, timeless and cerebral.

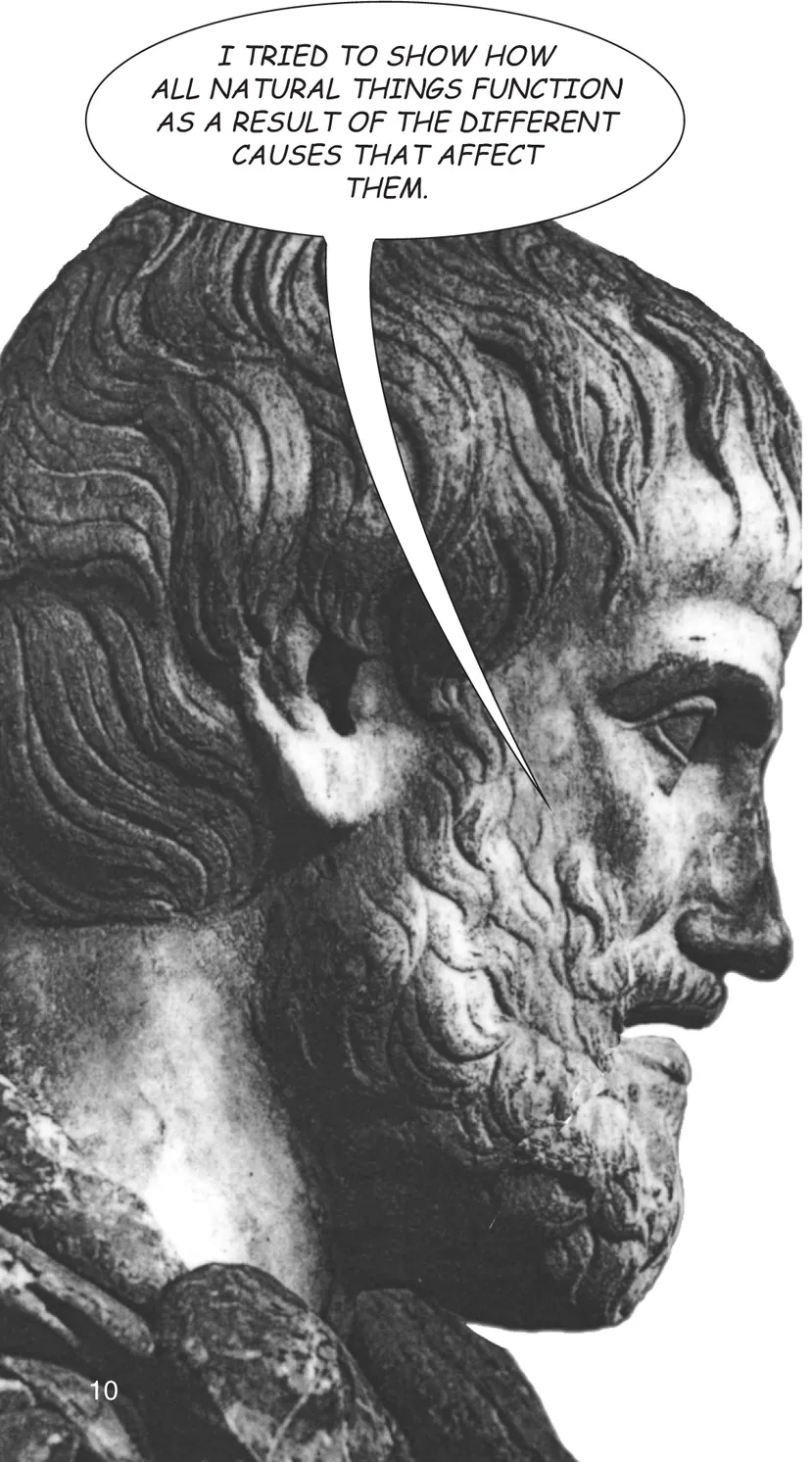

Aristotle and Observation

Plato’s famous student, Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.), disagreed. He thought that it was important to observe the world as well as do mathematics.

Aristotle was not a very methodical scientist by our standards. His observations were often tailored to fit his complex metaphysical theories. Muc...