![]()

Part 1

Background

![]()

1 The Eastern Cape, Then and Now

… although one is still in an area of special and outstanding beauty, it is not long before one is conscious of something more; an impression, seemingly, of a distinct and plangent power deriving from forces occult as well as visible, from an inner component of the malign set within a landscape whose natural attractiveness nevertheless has provoked more jealous antagonism and combat than any other in all Africa.Here on this frontier, between the last quarter of the eighteenth century and the end of the nineteenth century, was to be found the crucible of modern South African society.

Frontiers – Mostert (1992: xxi, xxii, xxix)

The four men whose life histories are the subject of this book are all descended from members of one or other of the earliest groups of white settlers in the Eastern Cape, who were initially all farmers. In this chapter, I look at the history of these groups of settlers, of the groups of indigenous people with whom the settlers interacted and the background to inter-group relations in the area. This means examining the wars and struggles of dispossession and resistance in which the participants’ forebears participated, patterns of land occupation and seizure, and labour relations and conditions on farms. Significantly too, in terms of the research, it means exploring language issues and multilingualism in the region, both historically and in the present. I do not go into detail about the more recent apartheid history, which is well known, but focus on the earlier history, linking it to current themes which feature in the men’s stories. The chapter culminates in a more detailed account of each of the four men’s lives. The oldest was born, as I was, around the time that the National Party took power in 1948, while the other three were born in the 1960s, when the implementation of the apartheid policy was getting into its stride (see Appendix 2).

In setting out the socio-historical context of the men’s stories, I draw on seminal works on the history of the Eastern Cape (Mostert, 1992; Peires, 1981, 1989) and South Africa (Giliomee, 2003; Sparks, 1991; Terreblanche, 2002), augmenting these with more specific information and alternative constructions from other sources. I also draw on novels and biographical works (Brodrick, 2009; Gregory, 1995; Johnson, 2006; Poland, 1993; Thomas, 2007), which give further details about the history and an insight into the atmosphere and mood, as well as personal and emotional responses to the times, often by multilingual white people. While most of the seminal works are written by white historians, I have endeavoured to include black perspectives, and to maintain a consciousness of how and by whom the events have been constructed.

Indigenous People and Early Settlers

At the time when the European ‘voyages of discovery’ were rounding the tip of Africa, a number of clans of the Nguni group of peoples lived on its south-eastern seaboard (Crampton, 2004; Peires, 1981). They grew some crops, but cattle formed the social, spiritual and economic basis of their society. Around 1600,1 the charismatic Tshawe overthrew his brother, the legitimate heir to one of these chiefdoms (Soga, 1931: 7), and united a number of fairly diverse groups and fragmentary clans to form the powerful amaXhosa (Peires, 1981: 15ff.). Descendants of Tshawe’s adherents still live in the Eastern Cape (and in many urban areas, especially around Cape Town), but the term Xhosa2 is now often used to refer loosely to all the groups coming from the Eastern Cape region who speak a language related to isiXhosa, the Nguni dialect which was written down by missionaries in the 19th century, thus becoming regarded as ‘standard’ isiXhosa.

In the 18th century, a difference of opinion over the appropriate behaviour for a Xhosa king caused the powerful Rharhabe to leave his brother Gcaleka, the heir to the throne, on the north-east side of the Kei River, and settle, with a large following, south-west of the Kei. This divided the amaXhosa in two: the amaGcaleka and the amaRharhabe (Mangcu, 2012: 52) (see Map 2, p. 5). Some independent chiefdoms, also recognising Rharhabe’s authority, moved across the Fish River into what became known as the Zuurveld (sour grassland) and beyond (Peires, 1981: 56). After Rharhabe’s death, the territory of his followers, under Ngqika and his regent Ndlambe,3 was to become a cauldron of war, as settlers of European origin moved into the area, seeking land and colonial dominion over the indigenous inhabitants.

Forebears of the four participants in this study are found in all of the main groups of early settlers to the Eastern Cape: Portuguese sailors, shipwrecked on the coast from as early as 1550 (Crampton, 2004), Dutch trekboers (travelling farmers) and British and German settlers.

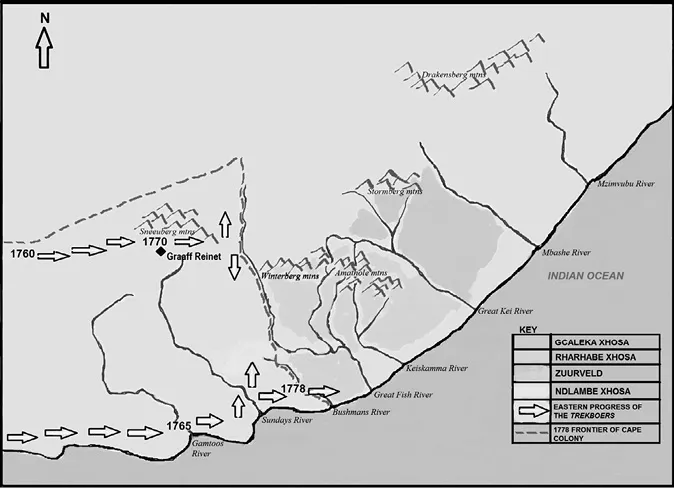

The trekboers were descendants of Dutch, French and German settlers at the Cape, who gradually moved further and further away from the constraints of the Dutch colonial government, seeking more grazing for their cattle. Map 2 (p. 5) shows that the paths taken by the trekboers eventually led some of them to areas west of the Great Fish River, some also moving into the Zuurveld, between the Bushmans and the Great Fish Rivers (Lubke et al., 1988: 395). Mostert (1992: 165ff.) graphically describes the restless lifestyle of the physically powerful trekboers, removed from the cultivated lifestyle of the Cape, beholden only to themselves and God, living and dying by their guns, and dependent on the Cape only for ammunition. In the period between the late 1820s and 1845, trekboers, motivated by a complex of reasons, most of which were related to their dislike of British domination and policies making them feel like aliens in what they regarded as their own land, moved out of the Eastern Cape in great numbers, seeking self-determination beyond the Orange River.4 Particular grievances were the change from the loan farm system to freehold title, the emancipation of slaves and the granting of equality before the law to Khoi5 and amaXhosa (Giliomee, 2003: 144ff., 161; Terreblanche, 2002: 220). Some trekboers remained in the Eastern Cape, and their descendants still live in the region.

Map 2: amaXhosa and trekboers, 18th century

Map drawn by E.K. Botha, acknowledgements to Wilson and Thompson (1969: 77) and Lubke et al. (1988: 395).

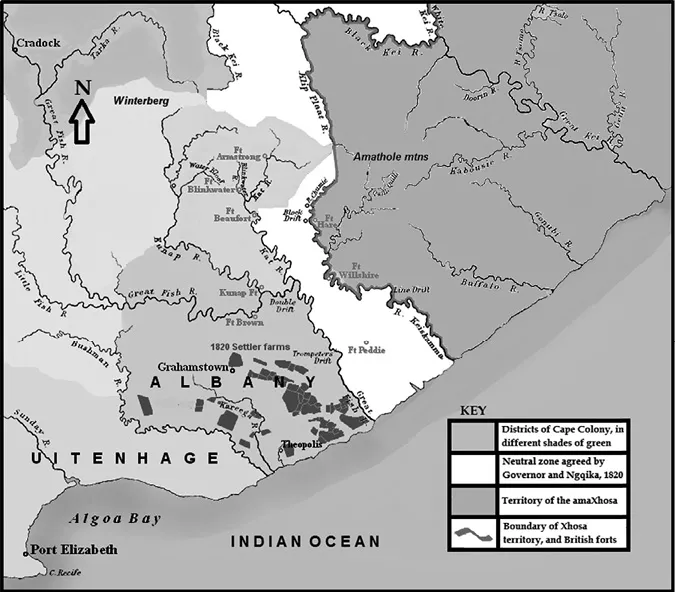

In 1820, the British, who ruled the Cape from 1806 onwards, recruited 5000 Britons, representative of all social strata of British life, to settle on farms in the Zuurveld area, renamed Albany (Sparks, 1991: 59) (see Map 3). The purpose of this settlement, not revealed to the settlers themselves at the time, was that they form a buffer against what the colonial authorities saw as the ‘inroads of the amaXhosa’ from across the Fish River, the then designated boundary of the colony. British settlers continued to immigrate to the Eastern Cape, a number in the early days coming as missionaries, attempting to win converts to Christianity from among the Khoi and the amaXhosa and using ‘education and literature to spread the gospel’ (Ndletyana, 2008: 2).

Map 3: British settlers, 1820

Map adapted from Wikipedia.org (2007) by E.K. Botha (2012).

Sparks (1991: 58) calls the 1820 immigration scheme, which gave each settler 100 acres, ‘an agricultural absurdity in the South African environment’, where a completely different approach was needed from that implemented in Europe. Following farming disasters during their first three years, including drought, blight, rust, locusts and floods, many settlers abandoned their allotments and moved to Grahamstown and Port Elizabeth, to form the backbone of commercial development in South Africa. Those who remained on the land enlarged their plots by taking over those that had been abandoned and turning to cattle ranching and later sheep farming. This put them in direct competition with the amaXhosa for cattle, and constituted the beginnings of commercial agriculture in South Africa. While many 1820 descendants moved far from the Eastern Cape, some still live on farms in areas where they were originally settled.

Almost 40 years after the arrival of the ‘1820 settlers’, when eight Wars of Resistance6 had been fought between the colonial powers and the amaXhosa, and the boundary of the colony had been shifted to the Kei River, the new British governor, Sir George Grey, settled military veterans from the British German Legion in the area stretching inland from East London (Tankard, 2009), and from 1858 onwards, he recruited German peasants to augment this group and provide wives for the soldiers (see Map 4, p. 13). These settlers (about 3400 in total), mostly poor peasant folk with no resources of their own, were given very small farms (20 acres at £1 an acre) and little government support (Brodrick, 2009; Schuch & Vernon, 1996). In spite of severe hardships, most of the German peasants persevered on the land, though some settled in town, taking up trades such as blacksmithing and wagon making. Many became productive agriculturalists, able to make a living for themselves, and a significant number of the descendants of the original German settlers are still farming in the area, or occupy other professional and commercial positions in the ‘Border’7 area.

These groups of settlers and indigenous peoples now faced the challenge of relating to one another, on land which they all needed for their stock. The trekboers’ progress into the hinterland from the Cape was characterised by fierce ongoing battles against the San8 (hunter-gatherers) and Khoi (wandering pastoralists) over cattle. Mangcu (2012: 49) maintains that ‘war between pastoralists and hunter-gatherers is inevitable because the latter want to eat what the former want to preserve’. While he notes that there were efforts on both sides to ‘stand together against the trekboere’, he also describes how the general commando combined all boer commandos9 and pressed Khoi into service to conduct a ‘genocidal campaign’ (Mangcu, 2012: 47) against the San. This resulted in the trekboers becoming dominant in the interior of the Cape colony (Penn, 2005; Terreblanche, 2002: 166).

Khoi people were often attached, voluntarily or by force, to boer families as servants, inboekelinge (serfs)10 (Terreblanche, 2002: 11), ‘clients’11 or even farming partners. In the early 18th century, the trekboers learned much from the Khoi ways of farming sheep and cattle in harsh, dry conditions (Terreblanche, 2002: 166), the Khoi in turn learning from the trekboers the skills of shooting and horse riding, as well as the their language (a form of Dutch). Khoi servants were thus often able to act as interpreters when the Dutch encountered new groups of people. Trekboers became notorious for their harsh treatment of Khoi servants, often similar to the way that slaves were treated in the Cape colony, except that the Khoi ‘violently resisted their enslavement’ (Terreblanche, 2002: 168). Attempts by British authorities and philanthropists to bring trekboers to justice for their harsh treatment were an important cause of the Great Trek of 1836.

Terreblanche (2002: 165) describes the relationship between trekboers and Khoisan as ‘changeable, dynamic and complex’. Mostert (1992) comments that conventional views of the trekboers’ racial attitudes obscure the

bizarre, fundamental ambivalence that operated within trekboer society. The trekboer not only turned to Khoikhoi women for cohabiting partners, but he often raised large families by them. He was, besides, wholly adaptable to Khoikhoi society, and could shift easily between his own and theirs if circumstances required. (Mostert, 1992: 175, 176)

Reports also indicate that in the areas west of the Fish River where the trekboers settled, they soon began to live ‘almost mixed together with the Kafirs’12 (Mostert, 1992: 226). Most of the Boers became fluent in isiXhosa, the language of the people among whom they found themselves.

The British settlers, by contrast, had very little contact with the amaXhosa initially; they were not allowed to employ the indigenous people as labourers (Mostert, 1992: 541), and a series of forts had been set up along the Fish River in an attempt to prevent the amaXhosa from coming into the colony. The settlers had little idea of the prior interactions between the British administration and the amaXhosa people, which had given rise among the Xhosa to fierce anger and resentment, so for many British settlers the Fifth War of Resistance,13 one of their earliest close encounters with the amaXhosa, was a shocking and unexpected experience. Mostert’s (1992) description of the attack on Christmas Eve 1834 reflects the colonists’ construction of the event:

[They] saw the surrounding hillsides livid with menace, ablaze with the massed red bodies14 that suddenly gathered there, and then liquid with scarlet movement as the whistling war-cry descended: a terrible sound, chilling in its undeviating and unmistakable purpose. (Mostert, 1992: 666)

The amaXhosa overwhelmed all white settlements, killing the men, burning and destroying houses and other property, and driving off thousands of cattle. ‘Their raging desire was to drive the British back into the sea’, claims Mostert (1992: 676). This war, which ‘swept away the toil of fourteen years in a matter of hours’, according to Butler and Benyon (1974: 259), had a brutalising effect on the British settlers. According to Sparks (1991: 62), it ‘… poisoned the racial attitudes of those settlers, deepening the ambivalences they had brought with them from “home”’. He elaborates on this ambivalence: while Britons believed strongly in democracy, they also believed that they were racially superior. Although British evangelical humanitarians pursued a liberal agenda, the English settlers facing the challenge of survival on a war-torn frontier had no time for humanitarianism. The war set up a burning hatred between the settlers and the philanthropists of the London Missionary Society, who promoted the cause of the indigenous peoples to the British government, resulting in equal rights legislation.

The German settlers, on the other hand, arrived on the frontier in the wake of eight Wars of Resistance and the episode known as the cattle killing (described and discussed under ‘Struggles for power and territory’), all of which had left the amaXhosa hugely depleted in terms of numbers and morale. The stated aim of the policies of the then governor George Grey, unlike that of his predecessors, was to encourage the ‘civilised coexistence’ of black and white in the Cape colony (Tankard, 2009). German settlers lived in close proximity to the amaXhosa and the amaMfengu15 people and they wrestled side by side with hardship and poverty. As Schuch and Vernon...