![]()

Part 1

Context

![]()

1Introduction

The face of classrooms and schools across the US is changing with more cultural and linguistic diversity today than ever before (US Department of Education, 2010). The student body in K-12 schools continues to become more linguistically diverse as the number of English learners (ELs)1 rapidly increases in classrooms in all corners of the nation (Gándara & Hopkins, 2010; Shin & Kominski, 2010). Representing a subgroup of children and adolescents who speak a native language other than English, students labeled as ELs are still in the process of attaining English as measured by standardized tests of language proficiency in speaking, listening, reading and writing (Linquanti & Cook, 2013). In the past decade, the population of ELs enrolled in US public schools has nearly doubled, climbing from 3.5 million to 5.3 million, with approximately 80% of students coming from Spanish-speaking homes and families (Gándara & Hopkins, 2010; National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition [NCELA], 2010). If the growth trend continues, one in every three students will be considered an EL by the year 2043 (Crawford & Krashen, 2007). Nevertheless, ELs are often the most underperforming student population in the US (Gándara & Hopkins, 2010).

The EL achievement gap (Fry, 2007) denotes the current reality that ELs’ academic performance remains substantially lower than their mainstream peers in nearly every measure of achievement (Gándara & Hopkins, 2010; Zamora, 2007). Minority students have long been juxtaposed from the mainstream in schools with the common assumption that diminished social resources outside of school leads to underperformance at school (Murrell, 2007). The historical trend of minority students having poor standardized test scores in comparison with mainstream peers’ scores has led to the oft-cited phenomena of the achievement gap – inequality of educational outcomes for African Americans, Latinos and Native Americans as compared to European Americans (Meece & Kurtz-Costes, 2001). When analyzing the academic outcomes specifically for those labeled as ELs, the achievement gap widens even further, demonstrating that US schools have not met the unique and diverse needs of this heterogeneous group of students (Fry, 2007; Heineke et al., 2012). For example, in a nationwide assessment of fourth-grade reading, 8% of ELs scored at or above the proficient level as compared to 40% of non-ELs; in eighth grade, only 4% of ELs scored proficient in contrast to 36% of non-ELs (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2015). Further exacerbating the issue of supporting and measuring ELs’ learning, standardized tests written for and statistically normed on native English speakers serve as the sole measure of EL student performance and achievement (Adebi & Gándara, 2006).

As educators and other stakeholders across the nation seek to understand and close the academic achievement gaps between native and non-native speakers of English (Fry, 2007), various questions continue to arise: What is the best way to educate ELs? How can educators support the teaching and learning of ELs? The persistence of EL achievement gaps throughout various approaches and models of language education has led national and international educational researchers and practitioners to fix the microscope on the recent shift in EL educational policy and practice in the southwestern state of Arizona (Carpenter et al., 2006; Fry, 2007). Adopting what scholars now deem to be the most restrictive educational context in the US for ELs, Arizona’s English Language Development (ELD) approach requires ELs to be separated daily from mainstream, English-speaking peers for four hours of skill-based, English language instruction with discrete blocks of time dedicated to grammar, vocabulary, conversation, reading and writing (Gándara & Hopkins, 2010; Heineke, 2015).

This text investigates this unique context of language policy in practice, honing in on the state of Arizona education for ELs five years after the initial implementation of the ELD approach to teaching and learning. Like peeling layers away from the dense and complex series of processes and policies that directly and indirectly influence EL education, the chapters that follow provide windows into the lived experiences of those engaged in the daily work of language policy. Drawing from the varied perspectives of teachers, leaders, administrators, teacher educators, lawmakers and community activists, the text presents the complex realities of restrictive language policy in practice for educators, stakeholders and readers to consider the definitive impacts on the large and growing population of ELs in the state and nation.

The State of Arizona Education

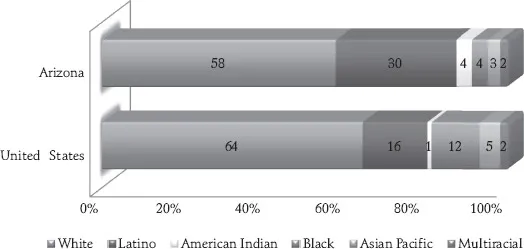

Situated on land that was Mexican territory prior to the Gadsen Purchase of 1854, Arizona’s geography includes a 370-mile border with Mexico; over 25% of the state’s land is designated for tribal reservations (Milem et al., 2013). In part because of the rich history of both groups in the Grand Canyon state, Latinos and Native Americans make up greater proportions in the state population than in the US as a whole (see Figure 1.1): twice the nation’s proportion of Latinos and four times the proportion of Native Americans live in Arizona (Milem et al., 2013). In Arizona classrooms and schools, the past 15 years have brought dramatic transformation in students’ racial and ethnic backgrounds, where students of color are the increasing majority. Latinos now surpass Whites as the largest group enrolled in Arizona K-12 classrooms (Milem et al., 2013). As a whole, Arizona K-12 education lags behind national averages and trends of student performance, with multiple data sets in the past decade showing negative gains across all demographic groups and academic subjects (Ushomirsky, 2013).

Figure 1.1 Arizona and US population demographics, 2010

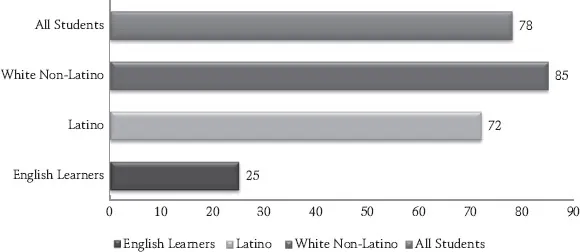

Challenges faced by ELs in classrooms across the state highlight the shortcomings of Arizona’s education system. Similar to the 51% growth nationwide, there was a 48% increase in ELs in Arizona schools in 10 years, with approximately 94% speaking Spanish as a native language (NCELA, 2010). The 166,000 ELs enrolled in Arizona schools in 2007–2008 comprised 15% of the state student population (Jiménez-Castellanos et al., 2013); however, existing policies and programming within the education system in Arizona have yet to make a meaningful dent in successfully supporting ELs’ development and achievement. In 2010–2011, 86% of Arizona ELs scored below basic proficiency on Arizona’s Instrument to Measure Standards (AIMS), whereas only 36% of non-ELs scored below; more shockingly, 13% of ELs scored at or above basic, in stark contrast to 64% of non-ELs (Haycock, 2011). Additionally, graduation rates vary based on language proficiency, with only 25% of ELs graduating from 4-year Arizona high schools compared to 85% of native English speakers (see Figure 1.2; Center for the Future of Arizona [CFA], 2013). Consistently ranking last nationally in per-pupil spending, scant EL funding has led to two decades of legal battles via the Flores v. Arizona case at both state and federal levels (Hogan, 2014; Jiménez-Castellanos et al., 2013). Despite the dismal state of educational opportunities for ELs in Arizona, educational deficiencies take a backseat to other issues concerning language minority populations that receive more national focus, such as immigration.

Arizona is currently the epicenter of the contemporary immigration debate in the US, making national and international headlines in recent years for controversial policies and practices. A growing anti-immigrant sentiment has pervaded Arizona for the past 15 years (Kohut et al., 2006), even as the number of undocumented immigrants soared 300% from 1996 to 2009 to an estimated 460,000 individuals (Sandoval & Tambini, 2014). Negative sentiments provoked anti-immigration movements and legislation, charged by local law enforcement and state lawmakers. What began with infamous Sheriff Joe Arpaio’s movement to enforce federal immigration policy at the local level in Maricopa County around the Phoenix metropolitan area (i.e. Section 287g of the Immigration and Nationality Act in 2007) evolved into the controversial ‘show-me-your-papers’ law in 2010 after the passage of Senate Bill 1070. Critiqued by opponents for its lack of reform to provide paths to legal residence or citizenship, SB 1070 nonetheless achieved proponents’ desired purpose of ‘attrition through enforcement’ (SB 1070, 2010: 1), as approximately 1000 undocumented individuals departed Arizona voluntarily through fear or involuntarily via deportation (Sandoval & Tambini, 2014). In recent years, this crisis has resulted in economic and educational decline as immigrant children and families have left the state, many of them ELs enrolled in Arizona schools (Jiménez-Castellanos et al., 2013; Milem et al., 2013).

Figure 1.2 Arizona 4-year high-school graduation rates

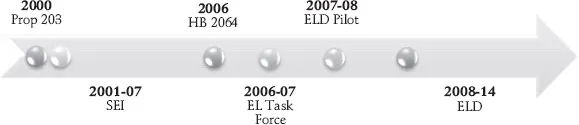

Pervasive anti-immigrant sentiments, corresponding to the presumed threat of linguistic diversity, led to widespread public support of educational policies touting English monolingualism (Crawford, 2000). Figure 1.3 summarizes notable language policies in Arizona. Situated between the successful English-only education movements in California (i.e. Proposition 227, 1998) and Massachusetts (i.e. Question 2, 2004), Proposition 203 passed in 2000, declaring English as the official medium of instruction in Arizona public schools and nearly eradicating bilingual education. Since then, Arizona schools have served as primary locales where monolingual and assimilative policies manifest in daily practice with culturally and linguistically diverse children and adolescents. Funded by millionaire software entrepreneur Ron Unz, the English for the Children campaign led voters to pass restrictive language policy by huge margins (Delisario & Dunne, 2000). To avoid submersion, or the sink-or-swim approach of placing ELs in English-only settings, policymakers called for Structured English Immersion (SEI), where ELs learn content and language simultaneously in classrooms with English-proficient peers (Echevarria et al., 2013).

Figure 1.3 Brief history of language policy in Arizona

When SEI did not improve ELs’ achievement, perhaps due to the lack of research base in the approach or the widespread implementation across the state, House Bill 2064 called for a more prescriptive, cost-efficient approach developed by the EL Task Force (Combs, 2012; Hogan, 2014; Krashen, 2001, 2004; MacSwan, 2004; Mahoney et al., 2004, 2005; Wright, 2005a). In the resulting ELD model, which went into effect in fall 2008, schools grouped students in classrooms based on language proficiency as determined and classified by the standardized Arizona English Language Learner Assessment (AZELLA). With 4 hours of mandated skill-based language instruction, ELD classrooms excluded typical content areas, such as science or social studies, to instead prioritize the explicit teaching of English-language reading, writing, grammar, vocabulary and conversation (Clark, 2009). Now multiple school years removed from the ELD implementation, this text explores the perspectives and experiences of educational stakeholders engaged in language policy work.

Language Policy Appropriation: Layers and Players

Language policy refers broadly to the management mechanisms, practices and beliefs that influence language use in a community or society (Shohamy, 2006; Spolsky, 2004). Traditionally, the field of language planning and policy emphasized the former, probing how nation-states strategically planned in attempt to resolve particular language problems (Fishman, 1979; Haugen, 1972). In this way, scholarship centered on the political authority’s top-down efforts to change daily language use, typically by targeting languages to serve as mediums of communication in public settings such as government, politics, commerce and education (Schmidt, 2000). In the past four decades, the field evolved as researchers captured the dynamism and complexity of language policy in local communities, recognizing the intersection of ideologies, official regulations, unofficial guidelines and practices as situated within unique sociocultural contexts (Johnson, 2013; McCarty, 2011; Ricento, 2000; Ricento & Hornberger, 1996; Shohamy, 2006; Spolsky, 2004). In this way, moving beyond an emphasis on the top-down planning processes of governments and political entities, language policy is understood to be more complex, referred to as ‘an integrated and dynamic whole that operates within intersecting planes of local, regional, national, and global influence’ (McCarty, 2011: 8). The educational domain exemplifies the complexity of language policy, where formal regulations and informal expectations attempt to manage and influence the language use of participants from varied language backgrounds, beliefs and repertoires within classrooms, schools and communities (Ricento & Hornberger, 1996; Spolsky, 2007).

Drawing from extant definitions and understandings in the field, I conceptualize language policy in practice as the ‘integrated and dynamic whole’ (McCarty, 2011: 6) that merges the interrelated and multidirectional facets of ideologies, paradigms, regulations and practices as situated within unique sociocultural contexts (Johnson, 2013; McCarty, 2011; Pennycook, 2000). Language ideologies are cultural systems of ideas, often discussed as beliefs, feelings, attitudes, assumptions and orientations concerning language use in a community (Gee, 2005; Ricento, 2000; Ruiz, 1984). Grounded in ideologies and often inconspicuously driving formal regulations, policy paradigms regulate what community members perceive as viable solutions and actions, described by scholars as unofficial, covert or de facto policies (Johnson, 2013; Mehta, 2013; Menken, 2008; Shohamy, 2006). Language policies, referred to here as policy regulations, are formal attempts to manage and standardize language use through power and politics (Spolsky, 2004). Johnson (2013: 9) describes this facet as ‘official regulations often enacted in the form of written documents, intended to effect some change in the form, function, use, or acquisition of language’. Policy practices emphasize the daily work of individuals across multiple layers of policy (Johnson, 2013). With daily communication in life and education occurring through language (Gee, 2005), individuals make decisions about...