![]()

Part 1

The Past, Present and Future

![]()

1 An Introduction to the Future

Ian Yeoman, Una McMahon-Beattie, Kevin Fields, Julia N. Albrecht and Kevin Meethan

Highlights

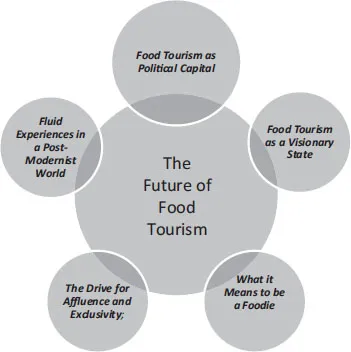

• Food tourism as political capital; food tourism as a visionary state; what it means to be a foodie; the drive for affluence and exclusivity; and fluid experiences in a post-modernist world are identified as the five core drivers of change that will shape the future of food tourism.

• Seventeen chapters portray the future of food tourism through recording how the past shapes the present, providing projections of the future, analysing key issues and concepts and highlighting future research avenues.

• With a systematic and pattern-based approach, this book presents an explanation of how and why change could occur and what the implications might be for the future of food tourism.

The Evolutionary Future of Food Tourism

The future

Pictures of the future can be large abstractions without explanation or truth. But in reality the future is an abstraction that has not happened. Pondering the future does not require truth nor explanation but to others it is all about truth and explanation. Confused, we are! Fundamentally is it a combination of truthfulness and plausible explanation. Our bias is towards explanation, as explanation is the rigour of science.

A future based upon prediction is founded upon certainty and a short time horizon whereas a science fiction future suspends all belief systems and looks for an explanation for how something could occur (Bergman et al., 2010).

Looking towards the future means understanding how change could occur, why it will occur and when it will occur. It is a combination of understanding dynamics, drivers, trends and pure speculation. Whether it is the price of wheat, changes in demography or pattern of affluence, sustainable agricultural production or tourist values, this book delves into the ‘big picture’ and explains what the future of food tourism could be.

The Past to the Present of Food Tourism

Food and tourism are the central features of this book. These topics have been around since the beginning of time:

It was the German bishop Johannes Fugger, in the 12th century who was journeying to Rome, his servant travelled a few days ahead to select suitable places to stay at, eat and drink. The servant would chalk ‘Est’ (Latin for ‘This is it’) on the doors of places deemed suited to the bishop’s taste. The inn in Montefiascone impressed the servant so much that he wrote ‘Est! Est!! Est!!!’ Legend has it that the bishop returned to Montefiascone on his way back from Rome to stay there for the rest of his life. (Domenico, 2001: 123)

Given that destinations generally provide visitors with food and drink, it is surprising that academic interest in food tourism is relatively recent. After all, food tourism refers to anything from street vendors and produce markets to high-end restaurants and large-scale food festivals. It comprises locally grown ingredients and regional cuisine as well as foodstuffs provided by global chains. Tikkanen (2007) even relates different types of food tourism to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, thereby validating the view that food and culinary tourism are not necessarily associated with high-priced visitor experiences only. Furthermore, food is undoubtedly an important part of the visitor experience (Cohen & Avieli, 2004); it is partaken on a daily basis and many take a great deal of pleasure in its consumption.

Indeed, one does not even need to travel exclusively in search of culinary experiences in order to become a food tourist: Yun et al. (2011) declare that only ‘deliberate’ food tourists travel specifically to seek out certain foods or ingredients. ‘Opportunistic’ food tourists may look for food and drink at a destination that they have selected for other reasons, and ‘accidental’ food tourists participate in food and drink just because it is there and they need to (Yun et al., 2011).

Other recent developments intensify the current surge in interest in food tourism both within destinations and academia. The emergence of celebrity chefs from the late 1990s onwards has increased awareness of food as a potential lifestyle factor. Chefs like Gordon Ramsay and Jamie Oliver in the United Kingdom and Rachael Ray and Mario Batali in the United States have contributed significantly to consumers’ knowledge of food and their appreciation of the provenance of ingredients. Not least due to the desire for authentic travel experiences, travel to places where ingredients or ‘branded’ food and drink such as Champagne or Parma originate is more popular than ever. Indeed, food tourism is one of the prime examples of a (supposed) niche product that allows visitors to take in all relevant aspects of a destination: product, process, place and people (Mason & Mahoney, 2007). Another important factor is the status that can be associated with travelling specifically in search of food or produce; while eating a Big Mac in as many countries as possible (Osman et al., 2014) may not improve one’s standing among one’s peers, an annual trip to sample the latest release of Beaujolais nouveau might.

The possible benefits for destinations are evident and can include increased visitor arrivals and lengths of stay; a new competitive advantage or unique selling proposition; more sales across the complete range of travel products including hospitality (both accommodation and meals/drinks), transport and retail; increased community pride, positive media coverage as well as tax revenue. While urban destinations such as for example New York or Sydney can add food tourism to their portfolio of tourism products, food tourism can open up previously non-existent streams of revenue for emerging destinations in agricultural regions.

It is surprising, then, that research on food tourism took off relatively late. Though there were some isolated case studies exploring food in the context of, mostly rural, tourism between the 1970s and the year 2000, food tourism as a subject of academic study gained in importance over the last 15 years. Topic areas covered include considerations of the definition of food tourism as well as related typologies (e.g. Hall & Sharples, 2003; Long, 2004), food tourism in the context of the wider destination (e.g. Hall et al., 2003; Mak et al., 2012), food and wine clusters, regional development (e.g. Boyne & Hall, 2004; Hashimoto & Telfer, 2006), destination identity (e.g. Hall et al., 2008; Sims, 2009, 2010), as well as critical perspectives on the role of food in tourism (e.g. Cohen & Avieli, 2004). Fundamentally, we have argued that food tourism has a history, is part of societies’ culture and – because of the relationship between food, communities and tourism – a topic of economic development to political leaders. Isn’t this exciting, read on!

The Future of Tourism: An Overview

The past, present and future

The first section sets the scene, focusing on how history shapes the present and, based on this, what the future could be. In Chapter 2, ‘The ‘Past” and ‘Present” of Food Tourism’, Boyd argues that current food tourism trends have a historical context and explores why food tourism has developed into its present form as production, consumption and experience. Boyd highlights the importance of the concepts of ‘local’ and ‘authenticity’ for the future of food tourism. Yeoman and McMahon-Beattie in Chapter 3, ‘The Future of Food Tourism: The Star Trek Replicator and Exclusivity’, portray two futures. First, they explore how science could change the food production process from a traditional land-based system to a laboratory-based one. Second, recognising the impact of food scarcity, they explore how food becomes an exclusive experience for rich tourists.

Food tourism

The second section explores the concepts and issues raised in section one and follows a scenario analysis from a supply perspective. Hansen in Chapter 4, ‘The Future Fault Lines of Food’, delves into the food supply chain arguing the today’s food is bland because of production systems and processes, thus speculating that the opportunity for food tourism is in developing flavours and senses that enhance the experience. Ells in Chapter 5, ‘The Impact of Future Food Supply on Food and Drink Tourism’, continues to focus on the supply chain and argues that the future of food tourism will involve an increasing number of food policy networks and actors within government, supply chains and consumer-centred groups working together to create a visionary future. Chapter 6, ‘Future Consumption: Gastronomy and Public Policy’ by Mulcahy argues that gastronomy has significance to all people at some level, and it can transform a state – each citizen and organisation doing their part, so that, collectively, the nation benefits, thus identifying the political, social, economic and cultural importance of food tourism. Danielmeier and Albrecht in Chapter 7, ‘Architecture and Future Food and Wine Experiences’, note how the role of place is and will be used to create uniqueness and points of difference in the architectural design of experiences in wineries. Hurley in Chapter 8, ‘Envisioning AgriTourism 2115: Organic Food, Convivial Meals, Hands in the Soil and No Flying Cars’, creates a utopian future that is based on an ecologically sound and socially just industry. Meethan in Chapter 9, ‘Making the Difference: The Experience Economy and the Future of Regional Food Tourism’, argues that future tourism developments need to be expressed in the context of globalisation thus shaping national and regional identity. Whereas, Fields in Chapter 10, ‘Food and Intellectual Property Rights’, argues the use of these tools is better positioned for the protection of history, culture, tradition and society than using them for the promotion of tourism.

Food tourism and the future tourist

In this section, a scenario analysis perspective delves into demand side issues, starting with Chapter 11, ‘Back to the Future: The Affective Power of Food in Reconstructing a Tourist Imaginary’, by Scott and Duncan, whose contribution revolves around how we see food as a significant motivation to travel, and so the chapter focuses on future food experiences through the tourist imaginary. Thus, Scott and Duncan suggest that food tourists make sense of the world around them an inherently imaginative process. In Chapter 12, ‘The Changing Demographics of Male Foodies: Why Men Cook But Don’t Wash Up’, Yeoman and McMahon-Beattie argue that men see cooking as a leisure activity whereas washing up is a chore. From a food tourism perspective they highlight three dimensions: namely, authentic food experiences, the masculinity of celebrity and media, and men as foodies in the sense that cultural capital defines their identity and status. In Chapter 13, ‘The New Food Explorer: Beyond the Experience Economy’, Laing and Frost’s contribution to the future of food tourism is to highlight the emergence of the food explorer as a niche market. The chapter identifies nine trends from slow food, artisan or organic food and produce, a desire for hands-on experience, sustainability, niche spaces, the exclusivity of the extreme, a preference for independent or experimental ordering or tasting, the view that local is best, and a rise in interest of foraging. Hay in Chapter 14, ‘The Future of Dining Alone: 700 Friends and I Dine Alone!’, notes that the known long-term changes in the structure of the population, the changing construct of the meaning of ‘family’ and the expected growth and dominance of single-person households in the Western world will all have a profound impact on the future evolution of the single diner states. Moscardo and colleagues in Chapter 15, ‘Dimensions of the Food Tourism Experience: Building Future Scenarios’, use both existing food tourism research and a study of tourist reviews to develop a conceptual model of food tourism organised around key consumption experience dimensions, including: learning destination place, personality, fun and stage.

Research directions

In the final section, two chapters conceptualise the future. Yoo in Chapter 16, ‘Food in Scholarship: Thoughts on Trajectories for Future Research’, contributes to tourism scholarship through the adoption of an interdisciplinary lens that links tourism and food studies, focusing on the elements of food as cultural heritage, food in scholarship, food as tourism attractions and a marketing tool, and tourist food consumption behaviour and dining experience. Finally Yeoman and colleagues in Chapter 17, ‘The Future of Food Tourism: A Cognitive Map(s) Perspective’, bring the book to a close by concluding the future of food tourism is clustered into five themes which are explained in further detail in the next section.

The Future of Tourism: Or Proposition

The aggregate contribution of this book to the future of food tourism is represented by Figure 1.1. These are the drivers of change that will affect future discourses, actions and behaviours in food tourism. Food Tourism as Political

Figure 1.1 Drivers of change

Capital notes that tourism incorporates discourses of economic, social and cultural benefit, which in itself results in political capital (Bourdieu, 1984). Food and agriculture are traditionally strong economic sectors with a strong political capital presence, thus when combined with tourism, food tourism is a beneficiary. Food Tourism as a Visionary State comes about as political capital takes the form of visions and utopias as food tourism is often portrayed through the words – ‘authenticity’, ‘sustainability’ and ‘activism’. Food tourism takes the form of a collective vision of utopia where the problems of humankind and climate change can be addressed.

Foodies are those tourists who are passionate about food and food is their main reason for travel (Yeoman, 2008). What it Means to be a Foodie is derived from the fact that food is the foodies’ avenue to cultural capital, where cultural production is increasingly becoming the dominant form of economic activity and securing access to the many cultural resources and experiences becomes an important aspect in shaping identity. The political drive for economic growth means that destinations will concentrate on high-spending markets (Yeoman, 2012), hence The Drive for Affluence and Exclusivity. Yeoman (2012) points out that with the arrival of mass tourism for the middle classes the definition of luxury becomes diluted and luxury providers need to redefine luxury as exclusivity. Yeoman recognises in a future society where food is scarce that the ingestion of food will reshape social and economic capital. Thus strategies will be based upon attracting more high-value, high-spending food tourists.

Increased affluence alters the consumer balance of power as new forms of connection and association allow a liberated pursuit of personal identity which is fluid and less restricted by background or geography. Tomorrow’s to...