eBook - ePub

Global Academic Publishing

Policies, Perspectives and Pedagogies

Mary Jane Curry, Theresa Lillis, Mary Jane Curry, Theresa Lillis

This is a test

Partager le livre

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Global Academic Publishing

Policies, Perspectives and Pedagogies

Mary Jane Curry, Theresa Lillis, Mary Jane Curry, Theresa Lillis

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

This book reports on the state of academic journal publishing in a range of geolinguistic contexts, including locations where pressures to publish in English have developed more recently than in other parts of the world (e.g. Kazakhstan, Colombia), in addition to contexts that have not been previously explored or well-documented. The three sections push the boundaries of existing research on global publishing, which has mainly focused on how scholars respond to pressures to publish in English, by highlighting research on evaluation policies, journals' responses in non-Anglophone contexts to pressures for English-medium publishing, and pedagogies for supporting scholars in their publishing efforts.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Global Academic Publishing est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Global Academic Publishing par Mary Jane Curry, Theresa Lillis, Mary Jane Curry, Theresa Lillis en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Business et Media & Communications Industry. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

BusinessSous-sujet

Media & Communications Industry1 | Problematizing English as the Privileged Language of Global Academic Publishing |

Mary Jane Curry and Theresa Lillis

In recent decades, English has been much heralded as the dominant language of global academic journal publishing, with estimates putting the prevalence of English use in academic journals at between 75% and 90%, depending on the discipline (see for example, Deng, 2015; van Weijen, 2012). In the context of global academic knowledge production, English is sometimes viewed positively as a lingua franca that facilitates the spread of ideas; in this vein, it is seen as replacing earlier linguae francae such as Latin and German (Sano, 2002). The rise of English in academic publishing parallels its reach across many academic domains in the present era of globalization, with English playing a key role in other trends such as the global mobility of students and scholars and as the medium of instruction in educational contexts outside of historically Anglophone ‘center’ nation states (Brock-Utne, 2007; Wallerstein, 1991). For scholars around the world, including in contexts where English is not the daily medium of communication, publishing in English can bring both benefits and detriments. In the increasing number of contexts where academic knowledge production has become commodified, publishing in English can yield prestige and material rewards (Lillis & Curry, 2010). It also enables many scholars to realize their interest in participating in international exchanges of ideas and research, with the desire for a shared intellectual language echoing utopian ideals about the free flow of knowledge (Ondari-Okemwa, 2007). In contrast, not publishing in English can carry negative consequences for certain scholars, such as being passed over for promotion, being denied salary increases or not being considered eligible to supervise doctoral students or to receive research funding (e.g. Queiroz de Barros, 2014). In many locations, therefore, multilingual scholars no longer face a decision about whether to publish in English; rather, their decisions focus on how to include English-medium publishing within their complex publishing agendas, which may include commitments to local knowledge production (Curry & Lillis, 2004, 2013a). This commitment typically requires additional time and other resources (Lillis & Curry, 2010).

Postgraduate students also increasingly face requirements to publish (in English) to earn their degrees, an aspect of the larger pressure to have published before entering the job market (e.g. see Huang, 2014). For many multilingual scholars and students, therefore, publishing in English has become an imperative (e.g. Ge, 2015; Graham, 2015; Lee & Lee, 2013), even while considerable academic publishing continues to be carried out in other languages. As our research has shown (e.g. Curry & Lillis, 2013a, 2014; Lillis & Curry, 2010, 2015), many dimensions of the social practices of writing for publication need to be considered in understanding how scholars engage with the growing pressures for publishing in English. One important dimension is scholars’ commitment to, and interests in, publishing in local languages for local audiences and therefore sustaining local research and other communities (Curry & Lillis, 2004). Another key dimension is multilingual scholars’ uneven access to the material and discursive resources that support English-medium academic publishing (Lillis & Curry, 2006a, 2013a). A related, overarching dimension entails how these problematics are addressed in institutional and governmental policies related to academic publishing and the rewards available for different types of publications (Curry & Lillis, 2013b).

Evaluation Regimes and the Role of English

Publications output has become an important aspect of the evaluation of individual scholars as well as the rankings of institutions on national, regional and global scales (Blommaert et al., 2005). The governmental and institutional policies that frame the evaluation of scholars’ work increasingly involve bibliometric measures such as the rankings of journals included in particular indexes and the journal impact factor (IF),1 which inherently promote or require the use of English (Feng et al., 2013; Lillis & Curry, 2010). Originating in the United States, the Web of Science (WoS) is a journal analysis service, owned by multinational corporation Thomson Reuters, that creates high-status citation indexes, publishes the influential Journal Citation Reports and keeps a ‘Master Journal List’ of the journals it draws on to create its products (www.wokinfo.com). WoS indexes overwhelmingly include journals that use some or all English (Lillis & Curry, 2013). In fact, despite the considerable research published in other languages, English-only journals predominate in the WoS indexes: currently, 87% of Science Citation Index (SCI) journals, 88% of Social Science Citation Indexes (SSCI) journals and 65% of Arts and Humanities Citation Index (AHCI) journals are English medium.2 English therefore plays a central role in the construction of the bibliometrics increasingly being used to evaluate the knowledge production activities of those working in higher education (Bardi & Muresan, 2014).Indeed, in response to pressures for greater accountability in higher education around the world, there has been a rise in the development and use of codified ‘evaluation regimes’ (Lillis, 2013), which increasingly use metrics of academic output. Such regimes instantiate the larger context of the ‘knowledge economy’, providing the frame for viewing academic publications as a measurable commodity, one that affects not only individual scholars’ careers but also the broader ability of a nation state or region to generate knowledge, generally seen to be a boon to economic activity (e.g. Englander & Uzuner Smith, 2013; Lillis & Curry, 2013: 220). Academic knowledge production in the form of research articles and patents is credited with supporting industrial innovations (Leydesdorff & Wagner, 2009) and economic development more broadly. In higher education, metrics of knowledge production also factor significantly in global rankings of universities (Hazelkorn, 2014: 23). For example, Shanghai Jiao Tong University uses six ‘objective criteria’ by which to evaluate universities for inclusion in its prestigious list, including

[the] number of highly cited researchers selected by Thomson Reuters, number of articles published in journals of Nature and Science, number of articles indexed in Science Citation Index – Expanded and Social Sciences Citation Index, and per capita performance of a university. (http://www.shanghairanking.com)

Similarly, ‘research’ and ‘citations’ factor as key criteria for the Times Higher Education World Universities Ranking (https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/2016/world-ranking#!/page/0/length/25). Journal publications (and the related IF, citations, etc.) are the key type of academic knowledge production counted in such ranking systems.

Evaluation and reward structures across geolinguistic contexts and academic disciplines involve both official policies and uncodified practices (Bardi & Muresan, 2014; Curry & Lillis, 2014; Lillis & Curry 2010). Around the world, evaluation criteria have been articulated in increasingly fine-grained ways, moving toward bibliometrics that involve English. Whereas, for example, scholars in Hungary were previously awarded more points for publishing in ‘foreign’ journals (including those using French and German) than in journals using Hungarian (Lillis & Curry, 2010), many evaluation regimes now specify publishing in journals included in the WoS indexes. Further, these regimes often assign value to a journal’s ranking in indexes or its IF (e.g. Lee & Lee, 2013). As only journals included in the WoS citation indexes are included in the official IF, using a journal’s IF as an evaluation criterion restricts the range of publication outlets that are institutionally rewarded. As a result, as competition grows to publish in these journals, journals that are excluded from WoS indexes – particularly those using languages other than English – become neglected. Overall, therefore, English is implicated in multiple aspects of the evaluation regimes for academic work within the global knowledge economy. As a result, the strong focus in governmental and institutional evaluation systems on the production of research articles – particularly English-medium articles published in journals that are included in prestigious indexes – shapes academic knowledge production in significant ways (Canagarajah, 2002; Lillis & Curry, 2010, 2015). Ultimately, the topic of academic publishing in English has serious implications for equity in global knowledge production.

Global Research Investment and Academic Productivity

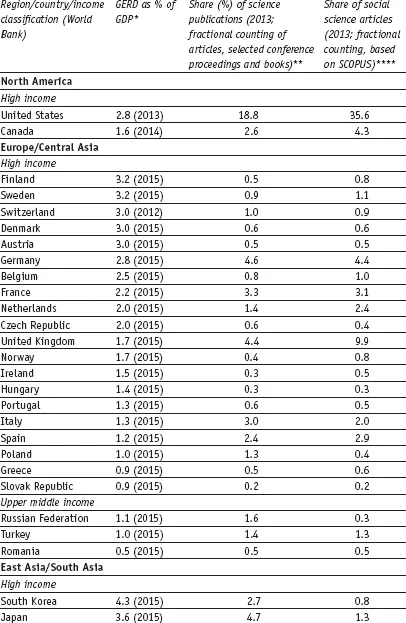

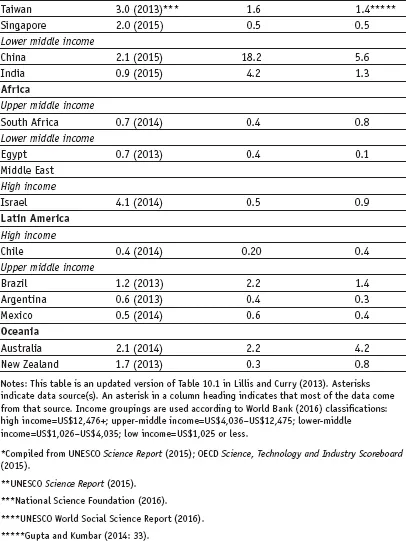

Scholars’ working conditions clearly affect their ability to contend with pressures to publish in high-status English-medium journals. However, research and policy discussions of academic evaluation regimes and policies related to knowledge production have generally neglected the central role of investment in research needed for institutions to provide the considerable material resources that scholars working in well-resourced contexts take for granted. The material and discursive resources required to conduct and publish research include funding for research activity; bibliographic resources, including books, journals and databases (Canagarajah, 1996, 2002); time; staff; supplies; (English-medium) text production support (Flowerdew, 2001; Lillis & Curry, 2006a, 2010); and travel to scholarly conferences where academic research networks can be forged and sustained (Curry & Lillis, 2010, 2013a). In many locations, these resources mainly come from government investment, although the source of such investment (government, business) and the extent of investment vary considerably across regions of the world. Table 1.1 lists general expenditure on research and development (GERD) as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) for selected top research-producing countries and regions of the world, as well as the share of global research publications of these countries in sciences and social sciences.As Table 1.1 shows, a few countries and regions produce the majority of research publications: Europe, the United States and, increasingly, high-income Asian countries – mainly China and Japan. Research investment directly affects the economic and material conditions in which scholars are able to undertake and then write about research. In recent years, for example, China has increased both its research investment and its global share of article publications, with GERD growing from 1.44% in 2007 to 2.1% in 2015 and its share of science articles growing from 7.4% to 18.2% in the same period. While other factors have clearly contributed to the increase in the case of China, the importance of research investment is clear, both in immediate material terms for researchers themselves and for their institutions and governments in being able to claim a higher share of global (English-medium) publications.

Table 1.1 GERD and share of world publications by global region and income level (selected countries)

Challenges to the Presumed Dominance of English in Academic Publishing

While what might be described as the centripetal pull (Bakhtin, 1981) of English-medium journal publishing seems secure, it is not uncontested. When attention is paid to multilingual scholars’ practices and experiences on the ground, a complex picture emerges of their pressures, challenges and responses (Bennett, 2014; Curry & Lillis, 2013b, 2014; Gentil & Séror, 2014; Hanauer & Englander, 2013; Lillis & Curry, 2010; Pho & Tran, 2016). Centrifugal challenges to the centripetal pull have arisen on multiple scales: responses from individual scholars, collective action by groups of scholars in specific contexts working to resist evaluation regimes, the development of English-medium journals outside of Anglophone contexts, the open access movement and the rise of alternative indexes. Concerns likewise are growing about the effects of the dominance of English on the sustainability of local knowledge as well as knowledge that has not historically been privileged within Anglophone traditions (e.g. Brock-Utne, 2007; Ishikawa, 2014).

In the past 20 years, the effects of the pressure to produce high status English-medium publications on scholars and their work lives have been well documented, with research consistently showing that such scholars identify the additional expenditures of time, energy, effort and resources required (e.g. Anderson, 2013; Bennett, 2014; Hanauer & Englander, 2011, 2013; for an overview, see Lillis & Curry, 2016). Depending on conditions and circumstances, scholars respond to pressures for English-medium publishing in various ways. At some moments, they adopt strategies aligned with official pressures for English-medium publication, while at other times they employ tactics that resist or subvert the pressure (Curry & Lillis, 2014). These tactics support scholars’ interests in developing local research cultures and local practice and reaching multiple audiences by, for example, engaging in ‘equivalent publishing’, that ...