eBook - ePub

The Social Reality of Europe After the Crisis

Trends, Challenges and Responses

Patrick Diamond, Roger Liddle, Daniel Sage

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 73 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

The Social Reality of Europe After the Crisis

Trends, Challenges and Responses

Patrick Diamond, Roger Liddle, Daniel Sage

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

The economic crisis of recent years continues to have a profound effect on the lives of European citizens. Economically, politically and socially, the crisis has led to fundamental change for many people's lives. As well as creating new concerns, the crisis has simultaneously exacerbated existing ones, raising profound challenges to the sustainability and success of the European model. This book seeks to examine this new 'social reality' of post-crisis Europe, exploring what both the EU and national governments can do to restore its strength, sustainability, cohesion and competitiveness.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que The Social Reality of Europe After the Crisis est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à The Social Reality of Europe After the Crisis par Patrick Diamond, Roger Liddle, Daniel Sage en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Politics & International Relations et European Politics. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

ECONOMIES AND LABOUR MARKETS

ECONOMIC GROWTH

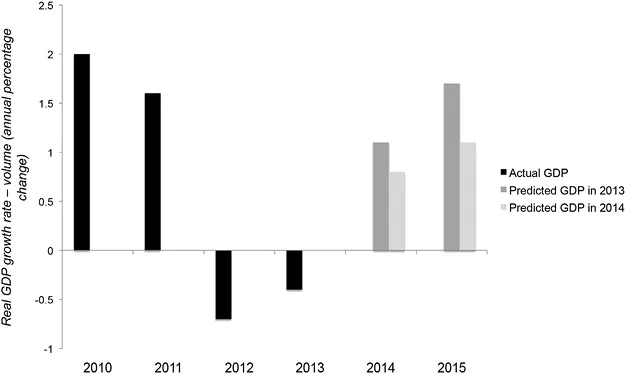

Although the most serious risks of the economic crisis such as a complete breakdown of the eurozone have seemingly now been averted (although at the time of writing, a Greek exit remains distinctly plausible), many European states nevertheless continue to endure anaemic economic growth and seemingly chronic structural weaknesses. In November 2014, the European commission significantly downgraded its forecasts for growth in the eurozone. In its February 2015 forecast, the commission pointed to ‘new developments . . . that are expected to brighten in the near term the EU’s economic outlook that would have otherwise deteriorated’. Predicted growth for the eurozone is now expected to rise from a sluggish 0.8 per cent in 2014 to 1.3 per cent in 2015 and 1.9 per cent in 2016. Crucially, Germany – the economic engine of the eurozone – has predicted growth of 1.5 per cent in 2015 and two per cent in 2016. This modest trend towards the return of to growth is put down to the decline in oil prices, the depreciation of the euro, the European Central Bank’s (ECB) embrace of a large-scale quantitative easing programme, and the commission’s own InvestEU investment plan. However, even on this more optimistic outlook, the commission still expects unemployment in the eurozone to average 10.6 per cent in 2016 and 9.3 per cent in the EU as a whole: this is considerably above the pre-crisis levels of 7.5 per cent and 7.2 per cent respectively.1

Even in Germany, which has been the EU’s greatest success story in terms of employment growth, the modest prospects of growth feed fears of a ‘German illusion’, the phrase coined by the economist Marcel Fratzscher to describe Germany’s apparent economic weaknesses and underlying vulnerabilities.2 In short, Fratzscher argues that Germany’s economic strength has been embellished by factors such as its labour market performance, with deep weaknesses in other areas of the economy, such as a comparatively low rate of domestic investment and a rapidly ageing population. On the other hand, Germany is increasingly at the centre of a cluster of countries such as Austria, the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia and Romania that excel in manufacturing and are where Europe’s industrial jobs are increasingly located.3 This shift in the pattern of manufacturing and supply chains has been a factor in the challenges of declining competitiveness and social sustainability that southern Europe faces.

The overall figures for the EU and the eurozone conceal vast differences in predicted economic performance. For instance, after years of sluggish growth and a ‘double-dip’ recession, Ireland and the UK are predicted to enjoy robust growth in 2016: 4.6 per cent in Ireland and 2.7 per cent in the UK. Nevertheless, claims of a resurgence of success in the UK in particular should be treated cautiously.

Figure 2.1 Actual and predicted GDP in the eurozone: 2010–15. Source: European commission.

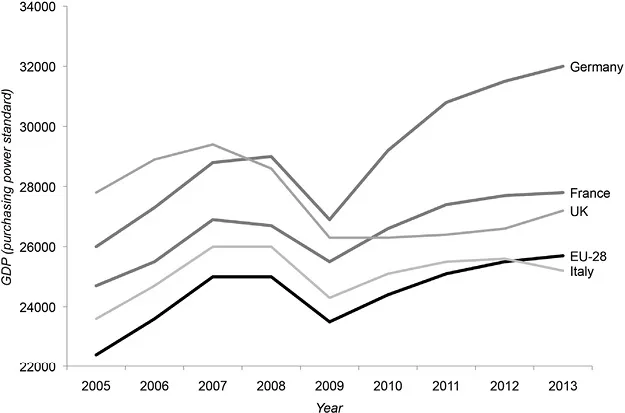

Figure 2.2 GDP per person in France, Italy, Germany and the UK: 2005–13. Source: Eurostat. Note: GDP per person in purchasing power standard.

Despite the gradual re-emergence of UK growth over the last 18 months (in part a bounce-back against the calamitous drop in output immediately after the financial crisis), and the strong growth in employment, a long-term view of economic performance indicates a deeper trend of relative UK decline compared to the major economies of continental Europe. In the years before the crisis among the four big EU economies – the UK economy had caught up with France and Germany, which had previously enjoyed the highest GDP per person levels in purchasing power standard (PPS).4

By 2005, the UK had a GDP per person PPS of 27,800: higher than Germany (26,000), France (24,700) and Italy (22,400). By 2013, however, the UK stood at 27,200. This was some way behind that of Germany (32,000) and even France (27,800), a trend that might seem surprising given the portrayal of the French economy as a ‘basket case’ by sections of the UK political and media establishment.

That the economic crisis has driven new trends in GDP growth in Europe is evident in the experiences of other countries in the EU. As Figure 2.3 indicates, the three northern European countries of Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden enjoyed steadily rising GDP per person PPS growth between 2005 and 2013. Equally in eastern-central Europe, the Czech Republic and Poland have continued to thrive economically. In particular, Polish growth has been remarkable: from a GDP per person PPS of 11,500 to 17,500 in eight years. This is part of the Polish ‘economic miracle’; in 2009, when the EU was in the darkest nadir of the crisis, Poland was the only EU economy that continued...