![]()

Part I

SHAME AND MORALITY

Chapter 1

An Unashamed Introduction to Shame

Shame is a distressing and depressing emotion. It is an emotion of disgrace, humiliation, or embarrassment that motivates one to hide and escape from others. It is a negative and destructive “sickness of soul.” Psychologists Tangney and Dearing (2002, p. 71) state that feelings of shame “involve fairly global negative evaluations of the self—the sense that ‘I am an inferior, inadequate, unworthy (or bad, immoral, unprincipled) person.’”1 Then how did it become a morally inspiring disposition of Confucianism?

Early Confucian philosophers believe that shame is a great moral disposition. In early Confucian texts such as the Analects, the Mencius, and the Xunzi, there are many passages where shame is praised and emphasized as a major moral virtue.2 Confucius, for example, recommends shame as an essential moral disposition that an ideal scholar official should develop.

Zi Gong asked, saying, “What qualities must a man possess to entitle him to be called an officer?” The Master said, “He who in his conduct of himself maintains a sense of shame.” (子貢問曰 何如斯可謂之士矣 子曰 行己有恥) (Analects, 13.20)3

From the perspective of people’s ordinary intuition and psychological analyses of shame’s negative and depressive tendencies, this passage is a puzzling statement that implies shame is a positive moral trait that one needs to cultivate. Why does Confucius praise and recommend such a negative and destructive emotion? Why shame?

As the above passage indicates, shame is a positive moral disposition and a wholeheartedly recommended character trait in Confucian moral tradition. In fact, shame is a major Confucian virtue. In early Confucian texts, the terms of shame such as chi (恥), xiu (羞), can (慚), kui (愧), and zuo (怍), appear more frequently than yong (勇), which refers to the virtue of bravery or courage. In the Mencius and the Xunzi, the terms of shame appear as frequently as xiao (孝, filial piety). It is not just the length or frequency of discussion but also the seriousness with which early Confucian philosophers discuss shame that makes it a unique Confucian virtue. Mencius, for example, considers shame as one of the four foundational moral emotions in his discussion of xiu wu zhi xin (羞惡之心, the mind of shame and dislike). Xunzi also carefully characterizes moral shame and separates it from other forms of shame, such as disgrace and embarrassment. Confucianism is perhaps the only school of philosophy that takes shame very seriously. Then, what is the moral significance of shame in Confucian ethics and how did it become a major Confucian virtue? In this chapter, I will conduct a comparative and interdisciplinary analysis of shame to explain its broad moral psychological nature and its moral significance in early Confucian philosophy.

WHAT IS SHAME?

It is not easy to define and analyze complex social emotions such as embarrassment, envy, empathy, guilt, and pride. Often, they seem to have vague boundaries with other emotions and seem to include mutually conflicting psychological components that motivate opposite behavioral tendencies. Jealousy, for example, is observed to be a psychological complex of love and hate. Envy seems to come out of a combination of resentment, bitterness, respect, and discontent. Shame is no exception. It has several distinct components that are combined to generate diverse feelings. The same pattern of complexity is observed in the meaning of the word “shame.” In English, shame has several distinct but interrelated meanings. The Oxford English Dictionary (1989) explains shame as “1. The painful emotion arising from the consciousness of something dishonouring, ridiculous, or indecorous in one’s own conduct or circumstances (or in those of others whose honour or disgrace one regards as one’s own), or being in a situation which offends one’s sense of modesty or decency.” “2. Fear of offence against propriety or decency, operating as a restraint on behaviour; modesty, shamefastness.” “3. Disgrace, ignominy, loss of esteem or reputation.” It seems that shame refers to diverse psychological, social, moral, and personal experiences but its main semantic foundation lies in one’s inappropriate behavior causing one’s disgrace, and concern for one’s vulnerable self being observed by others. In short, shame is an experience of the endangered self and the events, situations, or objects that cause such experience.

Upon careful inspection, however, one can find two distinct meanings of shame. On the one hand, shame is a self-critical or self-suppressive emotion of fear or dishonor but, on the other hand, shame refers to a sense of appropriateness that prevents one from committing shameful behaviors. For this reason, shamefulness and shamelessness, despite their apparent lexical contrast—sufficient and deficient forms of shame—raise a similar concern—shame proneness. If the former (shamefulness, “full” of shame) and the latter (shamelessness, “lack” of shame) converge in the similar sense of moral or social failure, the only way to explain the semantic affinity between the two is to suppose two opposite meanings of shame. Shame in the former refers to an experience or situation of social or moral inappropriateness. Shame in the latter relates to an active sense or disposition of appropriateness or decency. What shamefulness has is the shame in the former sense and what shamelessness lacks is the shame in the latter sense. In other words, shame has two opposite meanings: a feeling of social or moral failure and an ability to avoid it. In this regard, Lansky (1996, p. 769) explains the two dimensions of shame by saying that the English word “shame” is related to the desire to “disappear from view” or “comportment that would avoid the emotion (the obverse of shamelessness).”

The first semantic pole of shame is located in one’s stressful moral or social experience. When one’s inappropriate action is seen by others, one feels embarrassed and blushes for what he or she has done. Usually, this type of shame seriously affects, endangers, or destroys one’s honor, reputation, and ultimately one’s whole self that one has developed over a long period. So this type of shame is painful and stressful. It motivates one’s escape from others’ sight or the covering up of problems. The other semantic pole of shame is located in one’s moral or social aptness, a sense of appropriateness. Shame, in this sense, refers to what a shameless person lacks. A shameless person does not know what is right and appropriate and fails to behave accordingly, thereby committing deviant and unreasonable acts. So shame is a positive character trait, something one should be proud to have, but shamelessness is a character flaw that one should suppress and regulate. Figure 1.1 shows the two distinct semantic poles of shame.

As the diagram illustrates, shame in shamefulness and shame in shamelessness carry related but distinct and opposite meanings of shame. The former is a reactive (or retrospective) and self-critical emotion, but the latter is a proactive (or prospective) and self-conscious disposition. In other words, the two distinct and perhaps opposite semantic categories, i.e., a feeling of failure and a disposition of appropriateness, exist in shame words in English. In addition to the two semantic poles, shame can refer to events or situations. When people say “X is a shame,” X is an event or a situation that can potentially cause shameful experience. In this case, X is not a feeling or a disposition but an object of shameful experience or concern. The rightmost branch of the diagram shows this meaning of shame. Therefore, shame, at least in English, has three distinct meanings as illustrated in the diagram (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Meanings of Shame.

SHAME WORDS AND CONCEPTS IN DIFFERENT LANGUAGES

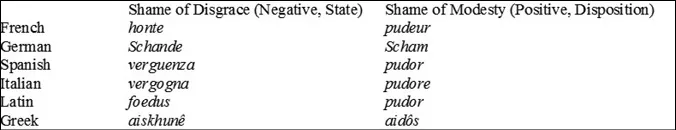

If one focuses only on the psychological meanings of shame, that is, the left side of the diagram (Figure 1.1), one can find the two general meanings of shame, namely, the stressful experience of dishonor, and the sense of modesty and appropriateness. This semantic distinction is broadly observed and respected in many different languages. In English, the two different meanings are differentiated semantically but not lexically: “shame” is the only word in English even though its two different meanings are clearly distinguished. In some European languages, however, the two meanings are not only semantically but also lexically distinguished. For example, honte and pudeur in French, Schande and Scham in German, verguenza and pudor in Spanish, vergogna and pudore in Italian, and foedus and pudor in Latin, all seem to make the similar distinction between negative-reactive and positive-dispositional senses of shame (Scheff 1991/2001, 7). Shame of disgrace and shame of modesty, according to Scheff (1991/2001), are the two major forms of shame recognized in many European languages.

Riezler (1943, pp. 462–463) reports that French, Greek, and German all have two words for shame and notes that “pudeur means a kind of shame that tends to keep you from act whereas when you feel honte after an act.” Lansky (1996, p. 796) also supports the distinction by assigning honte to the (shameful) emotion itself and pudeur to the defense of the self and its honor and integrity. Additionally, Scheff (1997, p. 209) sums up the distinction in French (honte, pudeur), German (Schande, Scham), and Spanish (verguenza, pudor) under the two general categories of disgrace and modesty and extends it to interpret earlier distinctions made between aiskhunê and aidôs in ancient Greek and foedus and pudor in Latin.4 Scheff (1997) believes that the distinction originated from antiquity and is generally observed in many modern European languages.

Table 1.1 Terms of Shame in European Languages

This view, however, is not unanimously accepted. Konstan, (2006, p. 98), for example, points out that aiskhunê and aidôs are not clearly categorized under disgrace and modesty, respectively.5 Nor does the distinction between Schande and Scham in German exactly follow the distinction between disgrace (negative shame) and modesty (positive shame). Perhaps they can be distinguished better by the cause and the feeling of shame. Scham is something one feels, but Schande is the cause of that feeling. Scham is not us...