![]()

Ireland

Shane Whelan

There is nothing unusual in the old age dependency ratio in Ireland as it evolves over the next century. However, there are significant differences in how Ireland’s pension system is designed to meet the challenge of an ageing society. Ireland and New Zealand are the only OECD countries that do not have a mandatory earnings-related pillar. Ireland’s state pension, like New Zealand’s, is a flat-rate pension.

Ireland’s pension system is simple in design. There is a state pension of about one-third of the average wage (currently €238.30 per week for the majority) with significant additions for dependents. This is a contributory pension, but the means-tested non-contributory pension is essentially worth the same amount. Pension provision above this minimum level is incentivised by the state through tax relief on contributions, tax relief on investment returns, and tax relief on some benefits (lump sum on death or retirement) with other benefits taxed as earned income.

The striking feature of the Irish pension system is that it has not changed over time: the system in 2017 is structurally identical to the one inherited with independence from the United Kingdom in 1921. Accordingly, one puzzle must be addressed in any study of the Irish system in an international context: how is it that the original system survived intact in Ireland, but required significant structural change in the UK and elsewhere? This puzzle is all the more baffling as the inadequacies that prompted change everywhere else are manifest and widely known in Ireland. As the OECD stated in a recent independent review of the Irish pension system:

A definitive choice should be made today regarding the structure of private pensions and its interaction with the State pension, with a view to implementation in the future. Given the many years that pension reform has already been discussed in Ireland without some fundamental choices being made about the way ahead, the time is ripe now to take some fundamental decisions on the future of Irish pensions. 1

The outline of this chapter is as follows. First, it reviews what changes there have been to the system from independence until today. Second, it gives a picture of how the system functions in 2017 in terms of coverage, security and adequacy. The following two sections contrast the high charges associated with personal pensions in Ireland to the value of the tax reliefs granted on pension saving above other savings, which are shown to be of the same order of magnitude. It concludes that the state’s subsidy to private pension provision maintains a large pensions industry, which does not satisfy any reasonable cost-benefit analysis. The penultimate section attempts to explain why pension reform in Ireland, though much discussed, has not happened despite the obvious failings of the current structure. It notes the failure of the state to act independently of the pensions industry in setting policy and regulation. It argues that Ireland is a case study of government failure, “in which the insurance companies had won and the workers of the country had lost”, as was observed more than half a century ago. It concludes that Ireland must adopt the first of William Beveridge’s three guiding principles – vested interests must not frame the reform agenda – if Ireland is to modernise its pension system and achieve a better outcome for the considerable state subsidy to private provision.

The development of the Irish pension system

The UK’s Old Age Pension Act 1908 granted non-contributory pensions to those over 70 years of age with limited means. Ireland was then one of the poorer regions in the UK and the effect of this act was to provide a near-universal pension of a generous amount, as the original five shillings pension was equivalent to half the wage of an unskilled labourer in Ireland. 2 The incentivising of private occupational pension provision through tax reliefs was established by the UK’s Finance Act 1921, 3 which carried through to Ireland following its independence in 1922. 4

The fiscally conservative government of the new Irish Free State tried to reduce the burden of pensions in its early years, a move that was politically unpopular and quickly reversed. In fact, until the Social Welfare Act 1960, there was to be only “incrementalist growth” in the system largely directed to overcoming the administrative difficulties in determining eligibility in a society when “systematic keeping of records of age and income are non-existent or ill-organised”. 5 The social welfare act 1960 introduced a contributory pension for all in paid employment excluding public servants, the self-employed (included a couple of decades later), and those earning above a threshold (included later), thus essentially giving the right to a pension irrespective of means. Like other pay-as-you-go social security systems, the contributions bear little relationship to the value of the pension entitlement. Further legislation in the early 1970s reduced the retirement age from 70 years to 66 or 65 in most cases. In more recent years, the retirement age has been increased: from 2028, it will rise to 68 years of age.

Private provision designed to top up the flat rate state pension comes mainly in the form of occupational pension schemes - the defined benefit scheme and more lately the defined contribution scheme. In addition, there has been some self-provision via individual retirement accounts of various descriptions. However, these top-up arrangements never covered much more than 50 per cent of the working population (including the public sector). Moreover, this coverage has declined over the last decade to less than 50 per cent of workers.

There was no change to the incentives for private pension provision although, of course, as income tax rates increased with time, the burden of the state’s subsidy (or ‘taxation expenditure’) grew. A modest level of regulation was introduced in private pension provision by the Pension Act 1990 and its subsequent amendments.

There have been many reports by those charged with advising the government on such matters, some even getting to the stage of green or white papers. For instance, in the 1970s, the debate in Ireland included consideration of transforming the state pension to an earnings-related system, in line with developments in the UK and elsewhere. A green paper was issued on the topic, but the white paper, though drafted, was never published. 6 When the UK was once again reforming its pension system, the Irish minister for social and family affairs requested the statutory advisory Pensions Board to conduct a full review of the Irish pension system. This produced the 2005 National Pensions Review and, at the further request of the minister, a supplemental report on a mandatory pension system based on individual accounts, Special Savings for Retirement (2006). These reports, augmented by survey studies of the operation of the existing system, 7 led to the 2007 Green Paper on Pensions. There was a formal and broad consultation process following publication of this green paper which came to nothing. Most recently the minister for social protection commissioned an independent review of the Irish pension system by the OECD. 8 .

Before we attempt to answer why so much talk about pension reform since Ireland’s independence has not translated into action, let us briefly review the current functioning of the system.

The current Irish pension system

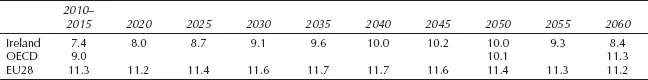

Ireland’s state pension is one of the least unaffordable systems in the world. This is simply because the size of the Irish state pension is lower than the average pension in most other countries. This has been true in the past and remains true if expenditures are projected over the next 50 years. Indeed, if all public expenditures on pensions in Ireland are considered – covering the contributory state pension, the non-contributory state pension and all public service pensions – then the picture is equally serene. Table 2, extracted from a recent OECD survey of pension systems across the world, shows that that projected annual expenditure peaks in Ireland in about 2045 at 10.2 per cent of GDP and that peak is lower than the current average expenditure on public pensions in the EU.

Table 2 Projections of Public Expenditure on Pensions, 2010–2060

Source: Abstract from Table 9.5 of OECD (2015).

There is scope to simplify the state pension system even further, in the direction of a universal pension. Perhaps there should be a more proportionate link between contributions made or credited and the eventual pension entitlement. However, these are minor adjustments. The key conclusion is that the Irish state pension is sustainable.

The state pension is the workhorse of the Irish pension system. The Central Statistics Office in Ireland shows that income for those over 65 years of age in 2011 comprised 63 per cent from state the pension and some other social transfers, 16 per cent from wages, 16 per cent from occupational pensions, 2 per cent from personal pensions and 3 per cent from investments. 9 In terms of relative poverty measures, the overall outcome, according to the OECD, is that “the economic situation of pensioners in Ireland is comparatively good, both with respect to other age groups in the population and internationally”. 10

The private system to top up the state pension functions less well. The CSO undertakes periodic reviews of private pension coverage. The latest review shows that 47 per cent of workers have a private pension, down by 7 per cent since the financial crisis. 11 . The main reasons cited by workers without a pension arrangement – now the majority in Ireland – is that they cannot afford it (39 per cent) or have not got around to it yet (22 per cent).

Those that do have a private pension have one largely because of their employer: of those with a private pension some 73 per cent have an occupational pension only, 18 per cent a personal retirement account only and nine per cent have both. The defined contribution arrangement has overtaken the traditional defined benefit scheme, ...