1

THE TABOO BABY

NEW ORLEANS, 1800–1900

Popular music gives shape, in time, to desire; and desire always crosses boundaries. In the United States, one line underlies all the rest: the artificial one separating the citizens who came to be called “white” from all the other people who inhabited the soil and shaped the nation. Music is so much more than the clearly delineated racial dialogue that several early-twentieth-century jazz musicians slyly called “black notes on white paper,” but it is that, too—a means for understanding the racial limits power imposes and the ways that, in lust, love, or careless leisure, people challenge, deny, reinforce, and momentarily obscure those limits. And so any discussion of America’s erotic musical life must confront the complexities of American race relations. It’s impossible to talk about it otherwise.

A close encounter with someone dangerously different was one of the most explosive possibilities of life in a young America. The fear of racial “mixing”—a more useful and musical term than the overused and stigmatized “miscegenation”—is as old as our colonial past, tied to an ideal of whiteness that was never pure and always embattled. Laws against intermarriage were adopted in Virginia and Maryland as early as 1691. Yet the mobility that kept America expanding continually challenged these hierarchies. In nascent culture capitals, immigrant cities like New York, frontier towns like St. Louis and San Francisco, and most of all in the cosmopolitan Southern center of New Orleans, daily life required the forward thinking to venture beyond their own kind—to exploit others and to learn from them. Able bodies worked together in the bustling streets of these entrepreneurial towns despite language barriers and wildly different points of origin, because the work had to be done; hierarchies of oppression temporarily unraveled in the processes of building and selling, though they were quickly reimposed. At leisure, men took pleasure from women as various as themselves, exploiting them, but sometimes also forging long intimacies. Many of these women danced in the saloons where they met their men: they danced Spanish cachuchas, Moorish alahambras, Greek romaikas. Music granted mobility, however provisional, to those marked as nonwhite—not just for these dancers but for leaders of all-black bands like James Hemmenway and Francis Johnson, who in the early nineteenth century forged a “Negro” sound that blended German military elements with Latin touches and an underlying African current.1 Music was often the language people employed to talk across lines of prejudice. On one level this tolerance and the leeway it afforded was all a delusion. Yet a vocabulary of freedom, not directly verbalized but written in the beats and tones between those black notes on white paper, began to form. It took well over a century for that feeling to gain the name rock and roll.

Here’s one story that says a lot about its time. Thomas C. Nicholls, a decorous military school student of seventeen, had spent all his years within fifty miles of Washington, DC, when, in 1805, his diplomat father summoned his family to join him at a new outpost: the recently acquired American port of New Orleans. Nicholls the younger left his studies at Maryland’s Charlotte Hall and joined his siblings and mother on an unpleasant journey aboard the ship Comet. Finally, they landed in the city on the southern banks of the Mississippi, which struck Nicholls as “revolting”—the buildings were ramshackle and windowless, the streets muddy, the tavern where he and his brother had to stay had no glass in the windows. But Nicholls found one aspect of his new home beautiful: its female residents, who lived to dance.

One night Nicholls relaxed at the home of a wealthy new friend, watching the women of the house prepare to attend a grand ball at one of the fifteen ballrooms that served this city of around ten thousand people. (The population would double within just a few years.) The women, attended by silent slaves, donned elaborate finery and then stood for inspection in front of their menfolk. The scene, as described by our young Northerner, evokes more brutal ones of slave and livestock auctions. But when they left the house, these human ornaments broke their bonds and became regular people out for fun. Nicholls wrote of this startling development in his memoir forty years later:

Everything prepared, the order was given to march; when, to my horror and astonishment, the young ladies doffed their shoes and stockings, which were carefully tied up in silk handkerchiefs, and took up the line of march, barefooted, for the ballroom. After paddling through mud and mire, lighted by lanterns carried by Negro slaves, we reached the scene of action without accident. The young ladies halted before the door and shook one foot after another in a pool of water close by. After repeating this process some half a dozen times, the feet were freed of the accumulated mud and were in a proper state to be wiped dry by the slaves, who had carried towels for the purpose. Then silk stockings and satin slippers were put on again, cloaks were thrown aside, tucked-up trains were let down, and the ladies entered the ballroom, dry-shod and lovely in the candle-light.2

The slaves were not permitted to join in the moment of disorder that put their mistresses in the mood to dance.

This remembrance is a pioneer story glorifying vigor at civilization’s edge. Had Nicholls been waxing poetic about discoveries he’d had a few states to the West, the ladies might have climbed into a covered wagon assisted by “noble savages.” Instead, his details reflected a different kind of American exoticism, whose elements were muggy heat, the romance languages of France and Spain, and the skin—from warm brown to earthy rust to coffee-with-milk to peachy—of a populace that called itself Creole and, according to Nicholls, was nearly as diverse as America would ever get.

The people themselves differed in complection [sic], costume, manners and language, from anything we had ever seen. The eternal jabbering of French in the street was a sealed book to us. Drums beat occasionally at the corners of the streets, suspended for a moment to allow the worthy little drummer to inform the public that on such and such a night there would be a Grand Ball at the Salle de Conde, or make announcements of a ball of another sort, for colored ladies and white gentlemen. Such were our visions of New Orleans in 1805.

At this time, New Orleans, which leaders had recently bought, was barely part of the new nation. Yet it already had many of the characteristics of a twenty-first-century megalopolis. The years of French and Spanish rule that preceded the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 established its polyglot nature, as did the city’s role as a hub of the slave trade, which connected it to the Caribbean and to Africa. In the streets, African-born residents of this active port carried heritage on their heads, in woven baskets containing the ingredients for gumbo z’herbes, an Americanized version of the diaspora stew callaloo. History rolled off their tongues in newly forming dialects. Free blacks mingled with Irish and Italian immigrants, mixed-blood Creoles, and slave artisans, who ran small shops for the profit of their owners.

Scenes like the ones Nicholls recalled, which became commonplace among travel writers as the century unfolded, created the image of New Orleans as the kitchen garden of American hedonism. To be intrepid here was to seek pleasure as much as material prospects, and this desire to be sensually fulfilled was often attributed to the mixed-up blood of the city’s residents. Not only did African people, slave and free, move more freely in New Orleans than they did in many other cities; deep connections to the Latin and French communities differentiated even the so-called whites of the town.

“Those called the Whites are principally brunettes with deep black eyes; dark hair, and good teeth,” wrote Thomas Ashe, an Irish travel writer primarily known for spinning tall tales of the American West, in 1806. “Their persons are eminently lovely, and their movements indescribably graceful, far superior to any thing I ever witnessed in Europe. It would seem that a hot climate ‘calls to life each latent grace’ . . . In the dance these fascinating endowments are peculiarly displayed.”3

Such descriptions of languid, vaguely Mediterranean Louisiana belles fed into the widespread belief that the South was a place where morals ran as loose as the temperatures ran hot. Abolitionist rhetoric furthered the linkage of plantation life and debauchery. Historian Ronald G. Walters calls this “the Erotic South.” “Plantations, like a moralist’s equivalent for the settings of pornographic novels, were simply places where the repressed could come out of hiding. Abolitionists saw both what was actually there—erotic encounters did occur—and what associations of power with sex prepared them to see.”4

The mix is the fundamental form of all American popular arts. Born of Saturday night dance battles in rural barns or urban squares, and of songs shared among family members or workingmen in saloons, the music and movement that uniquely belonged to this country were a conglomeration from the beginning. The mingling and mutual appreciation forbidden by law among individuals was constantly enacted symbolically, especially in music and dance. And often, what singers said and how dancers shook and shimmied brought into the open the erotic charge of such encounters. The story of how American music and American sex shaped each other doesn’t only begin in New Orleans, but the city’s erotic excitement, racial anxiety, and openness to mixing arose early and was noticed. The effect, which theorist Tavia Nyong’o has dubbed “the amalgamation waltz,” still feeds American pop. It’s what made Miley Cyrus’s hips go up and down.5

Scholars have struggled to come up with a powerful term to describe American hybridity that doesn’t also reinforce stereotypes. Eric Lott’s famous formulation of minstrelsy, the foundational form through which white Americans appropriated African American culture as “love and theft,” remains the most widely invoked—Bob Dylan even used the phrase as an album title in 2001.6 But the necessary uncovering of minstrelsy as the source of so much twentieth-century popular culture has led us to overstress the most theatrical appropriations of identity, instead of harder-to-track histories of more common and close-quartered musical encounters. Before the 1830s, when the white itinerant comedian Thomas Rice became widely known for his “Jim Crow” routine, whites and blacks were learning each other’s dance steps in ballrooms and plantation parlors and commenting on each other’s daily lives in domestic songs. Dance-based or informally voiced expressions of cultural mixing were more widespread than theatrical ones and included all members of American society, including children and women who were not professional entertainers. Music played in the streets and at home could trip into anyone’s life. It could feel like a gift, or a violation.

A music-inspired brawl that the New Orleans Times-Picayune reported in 1850 was emblematic of the whole period:

Elizabeth Hyser, a young lady with a red skirt, gipsy hat and blooming countenance, yesterday appeared before Recorder Genois, and made a terrible complaint against Andrea Lobeste, whom she charges with having assaulted her with a dangerous weapon on the levee. It appears that she was discoursing eloquent music on her tamberine, as an accompaniment to an ear-piercing organ, when Mr. Lobeste expressed his disapprobation of the entertainment by cutting up her tamberine with a knife. This grave matter will be inquired into.7

Although Hyser’s name is German, the way she’s described makes her a racial amalgam. Her “gipsy” hat hints at the Latin tinge that has always been essential in American music, and her tambourine was originally a North African instrument. Accounts of New Orleans in the first half of the eighteenth century abound with scenes like this one. And they’re almost always set to a lively beat.

The fact of race mixing was amplified through the fear of it—and the excitement it stimulated. Abolitionist declamations that THE SOUTHERN STATES ARE ONE GREAT SODOM formed a hysterical counterpoint to appreciations of the free and easy Southern life published in magazines and travelers’ diaries.8 The true extent of sexual intimacy among people of different races and ethnicities during this period is very difficult to determine. What was real in this polyglot place, and what spun out quickly into myth? How did these mixing, melding, clashing bodies move?

As many chroniclers like Nicholls noted, New Orleans was dance-mad. The fifteen ballrooms he found upon arriving offered entertainment every night of the week, and their number doubled in the next decade. There were balls for the white and Creole upper crust, for free people of color, and even for slaves; there were children’s balls and smaller soirees in people’s homes. People danced every afternoon on the levee and sometimes out in the Tivoli Gardens amusement park at Bayou St. John.9

In the ballrooms, British reels and French quadrilles preserved and expanded the customs of disparate homelands and brokered evenings of peace within a newly multicultural community. Nationalist tensions sometimes burst through the genteel façade, as in the great “quadrille wars” of 1803, when conflicts over whose national dances were performed led to duels and, one memorable night, to the ladies of the party fleeing into the night after someone shouted, “If the women have a drop of French blood in their veins, they will not dance!”10 Mostly, though, music became the medium through which dancers absorbed the city’s myriad subcultures—even ones that law and propriety might have kept them from openly embracing.

African musicians, slave and free, played in bands, just as they did at parties on plantations. The architect Benjamin Latrobe witnessed one such music maker at a ball he attended in 1819, a “tall, ill-dressed black, in the music gallery, who played the tambourin standing up, & in a forced & vile voice called the figures as they changed.” The fiddle was also a pacifying force used by slavers to create an illusion that, in their galleries, those people being torn from their families and put into chattel were actually as merry as the tunes one of them played. So music was both a tool of oppression and the weapon that could momentarily defeat it. In Solomon Northup’s slave narrative, recently brought to light again by director Steve McQueen’s 2013 film version 12 Years a Slave, the fiddle he calls “notorious” allowed him to travel well beyond the borders of his master’s plantation, but also caused him agony when his keeper forced him to use it as others were whipped until they danced.11

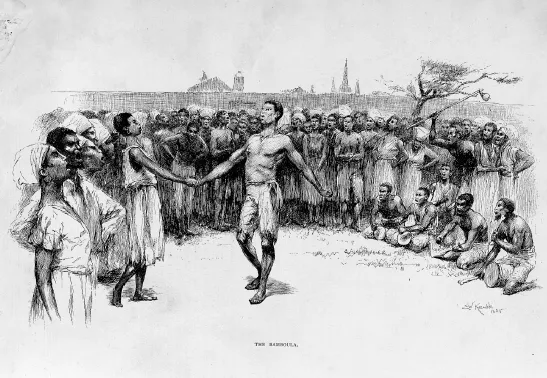

Slaves did dance in happier circumstances, too, on holidays and other fleeting occasions, sometimes alongside free folk. What effect did European music that incorporated African and Latin elements have on the dancers who willingly and joyfully moved to it? The rhythms of the diaspora are hard to trace within the straight lines of sheet music, which is our primary evidence of this period’s sound. But accounts suggest that what jazz historian Marshall Stearns called “rum in a teacup”—“the addition of Congo hip movements to the dances of the court of Versailles”—gave many local dances the added kick that travelers to New Orleans celebrated. The choreography of European dance was still performed, but in a new way—with hips swinging, shoulders delicately shaking, and feet moving more quickly.12

This is probably how the women who’d removed their shoes to get to t...