![]()

1

Hunters and Farmers

c. 2.5 million–3000 BC

![]()

Our story begins with a rapid survey of a vast span of time from about 2.5 million years ago to about 3000 BC. During this period, as a product of biological, cultural, and social evolution, four radical transformations took place. First, in East Africa, 2.5 million years ago, some apes evolved into the earliest hominids – animals that walked upright and whose hands were henceforward free to fashion tools. Second, about 200,000 years ago, again in Africa, certain hominids evolved into modern humans, creatures with larger brains and a greater capacity for tool-making, collective labour, social organisation, and cultural adaptation to different environments. Third, about 10,000 years ago, under the impact of climate change and food shortages, some communities made the transition from hunting and gathering to farming. Fourth, about 6,000 years ago, new techniques of land reclamation and intensive farming allowed some communities in favoured locations to increase their output substantially by moving from hoe-based cultivation to plough-based agriculture.

I call these transitions revolutions to signal the fact that they were relatively abrupt: moments in history when the steady drip-drip of evolutionary development suddenly tipped over into qualitative change – from walking on all fours to walking on two legs; from a hominid of limited intellect to one of exceptional ability; from a way of life based on foraging or hunting for food to one based on producing it; and from hoe-based to plough-based farming. By the end of this period, around 3000 BC, farming was supplying human societies with agricultural surpluses sufficient to support religion, war, and groups of specialists. From among the latter, who usurped control of the surplus, the first classes of exploiters would emerge.

The Hominid Revolution

A new form of ape roamed the Afar Depression of Ethiopia 3.2 million years ago: Australopithecus afarensis (‘southern ape of Afar’). Anthropologists recovered 47 fossil bones of one of these ‘australopithecines’ in 1974, some 40 per cent of a complete skeleton. From the slight, gracile form, they assumed she was female and dubbed her ‘Lucy’, but she may in fact have been male.

Lucy stood just 1.1 m tall, weighed around 29 kg, and was probably about 20 years old when she died. With short legs, long arms, and a small brain case, Lucy would have looked rather like a modern chimpanzee. But there was a crucial difference: she walked upright. The shape of her pelvis and legs, and the knee joint of another member of the species found a short distance away, proved this beyond reasonable doubt.

Lucy was probably one of a small foraging group that moved around gathering fruit, nuts, seeds, eggs, and other foodstuffs. As climate change reduced the forests and created savannah, natural selection had favoured a species able to range over greater distances in search of food. But Lucy’s bipedalism (walking on two legs) had revolutionary implications. It freed the hands and arms for tool-making and other forms of labour. This in turn encouraged natural selection in favour of larger brain capacity. A powerful dynamic of evolutionary change was set in motion: hand and brain, labour and intellect, skill and thought began an explosive interaction – one which culminated in modern humans.

We do not know whether Lucy made tools. None was found in association with her remains or with those of her companions. But 2.5 million years ago Lucy’s descendants certainly did. Choppers made from crudely chipped pebbles represent the archaeological imprint of a new family of species defined by tool-making behaviour: the hominids. Tools embody conceptual thought, forward planning, and manual dexterity. They reveal the use of intellect and skill to modify nature in order to exploit its resources more efficiently. Other animals simply take it as it comes.

The hominids, like the australopithecines before them, evolved in Africa, and for about 1.5 million years that is where they largely remained. Although 1.8-million-year-old fossil remains have been found in Georgia, near the Black Sea, these appear to represent only a brief foray into Western Asia. Not until about a million years ago did a species of early human, Homo erectus, migrate from Africa to colonise much of South and East Asia. Later again, a more developed hominid, Homo heidelbergensis, settled in much of Western Asia and Europe. But these populations were tiny and unstable.

Hominids are creatures of the Ice Age epoch which began 2.5 million years ago. Ice Age climate is dynamic, shifting between cold glacials and relatively warm interglacials. We are currently in an interglacial, but 20,000 years ago much of Northern Europe and North America was in the middle of a glacial and covered by ice-sheets up to 4 km thick, with winters lasting nine months, and temperatures below –20°C for weeks on end. The early hominids were not adapted to the cold, so they migrated north in warm periods and moved south again when the glaciers advanced. They first arrived in Britain, for example, at least 700,000 years ago, but then retreated and returned at least eight times. Britain was probably occupied for only about 20 per cent of its Old Stone Age (c. 700,000–10,000 years ago).

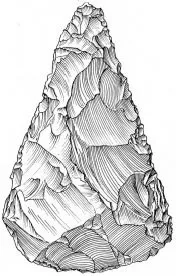

Homo heidelbergensis seems to have inhabited coastal or estuarine regions, where animal resources were rich and varied. The standard tool was either an ‘Acheulian’ handaxe – essentially a chopper – or a ‘Clactonian’ flake – a cutter. These general-purpose tools were mass-produced as needed. Excavations at Boxgrove in England recovered 300 handaxes and much associated flint-knapping debris dating to around 500,000 years ago. They had been used to butcher horse, deer, and rhinoceros on what was then a savannah-like coastal plain.

During the last glaciation, however, there was no wholesale retreat. Homo neanderthalensis was a cold-adapted hominid that evolved out of Homo heidelbergensis in Europe and Western Asia about 200,000 years ago. Neanderthal adaptation was a matter of both biological evolution and new technology. With large heads, big noses, prominent brows, low foreheads, little chin development, and short, squat, powerfully built bodies, the Neanderthal was designed to survive winters with average temperatures as low as –10°C. But culture was more important, and this was linked to brain power.

Hominid brains had been getting bigger. Selection for this characteristic was a serious matter. Brain tissue is more expensive than other kinds: the brain accounts for only about 2 per cent of our body weight but no less than 20 per cent of food-energy consumption. It is also high-risk. Humans are adapted for walking upright, which requires a narrow pelvis, yet have a large brain-case, which imposes a strain on the woman’s pelvis in childbirth; the result is slow, painful, and sometimes dangerous birth trauma. But the advantages are considerable. Large brains enable modern humans to create and sustain complex social relationships with, typically, about 150 others. Humans are not just social animals, but social animals to an extreme degree, with brains especially enlarged and sophisticated for this purpose.

Sociability confers enormous evolutionary benefits. Hominid hunter-gatherer bands were probably very small – perhaps 30 or 40 people. But they would have had links with other groups, perhaps half a dozen of similar size, with whom they shared mates, resources, labour, information, and ideas. Sociability, cooperation, and culture are closely related, and achieving them requires high levels of intelligence: in biological terms, brain tissue.

The Neanderthals were certainly clever. The ‘Mousterian’ tool-kit of the classic Neanderthals contained a range of specialised points, knives, and scrapers – as many as 63 different types according to one famous study of archaeological finds from south-western France. Intelligent, networked, and well equipped, the Neanderthals were superbly adapted to Ice Age extremes, building shelters, making clothes, and organising themselves for large-scale hunting on the frozen plains. Lynford in England is a hunting site dating from 60,000 years ago. Here, archaeologists found Neanderthal tools associated with the bones, tusks, and teeth of mammoths.

But natural organisms are conservative in relation to their evolutionary perfection. The Neanderthals, in adapting so well to the cold, had entered a biological cul-de-sac. Meanwhile, in Africa, the crucible of species, a new type of super-hominid had evolved out of the ancient erectus line. Such was its creativity, collective organisation, and cultural adaptability that, migrating from Africa 85,000 years ago, it spread rapidly across the world and eventually colonised its remotest corners. This new species was Homo sapiens – modern humans – and it was destined to out-compete all other hominids and drive them to extinction.

The Hominid Revolution, which began around 2.5 million years ago, had culminated in a species whose further progress would be determined not by biological evolution, but by intelligence, culture, social organisation, and planned collective labour.

The Hunting Revolution

Somewhere in Africa, 200,000 years ago, lived a woman who is the common ancestor of every human being on earth today. She is the primeval progenitor of the entire species Homo sapiens – modern humans. We know her as ‘African Eve’. It is DNA analysis that has revealed this, confirming and refining the conclusions reached by other scientists based on the evidence of fossilised bone.

DNA is the chemical coding within cells which provides the blueprint for organic life. Similarities and differences can be studied to see how closely various life forms are related. Mutations occur and accumulate at fairly steady rates. This allows geneticists not only to measure biological diversity within and between species, but also to estimate how much time has passed since two groups separated and ceased interbreeding. Mutations in our DNA therefore constitute ‘fossil’ evidence of our past inside living tissue.

The DNA date for African Eve matches the date of the earliest known fossils of Homo sapiens. Two skulls and a partial skeleton found at Omo in Ethiopia in 1967 have been dated to c. 195,000 BP (before the present; the usual term when discussing hominid evolution).

The new species looked different. Early humans had long, low skulls, sloping foreheads, projecting brow ridges, and heavy jaws. Modern humans have large, dome-shaped skulls, much flatter faces, and smaller jaws. The change was mainly due to increased brain size: Homo sapiens was highly intelligent. Big brains make it possible to store information, think imaginatively, and communicate in complex ways. Language is the key to all this. The world is classified, analysed, and discussed through speech. African Eve was a non-stop talker. Because of this, in evolutionary terms, she was adaptable and dynamic.

Homo sapiens had this unique characteristic: unlike all other animals, including other hominids, she was not restricted by biology to a limited range of environments. Thinking it through, talking it over, working together, Homo sapiens could adapt to life almost anywhere. Biological evolution was therefore superseded by cultural evolution. And the pace of change accelerated. Handaxe-wielding Homo erectus had remained in Africa for 1.5 million years. In a fraction of that time, the descendants of African Eve were on the move. Or some of them were. The genetic evidence appears to show that the whole of Asia, Europe, Australia, and the Americas were populated by the descendants of a single group of hunter-gatherers who left Africa about 3,000 generations ago – around 85,000 BP. South Asia and Australia were colonised by 50,000 BP, Northern Asia and Europe by 40,000 BP, and the Americas by 15,000 BP.

Why did people move? Almost certainly, as hunter-gatherers, they went in search of food, responding to resource depletion, population pressure, and climate change. They were adapted for this – adapted to adapt. Designed for endurance walking and running, they were capable of long-distance movement. Their manual dexterity made them excellent tool-makers. Their large brains rendered them capable of abstract thought, detailed planning, linguistic communication, and social organisation.

They formed small, tight-knit, cooperative groups. These groups were linked in loose but extensive networks based on kinship, exchange, and mutual support. They were, in the sense in which archaeologists use the term, ‘cultured’: their ways of getting food, living together, sharing tasks, making tools, ornamenting themselves, burying the dead, and much else were agreed within the groups and followed set rules.

This implies something more: they were making conscious, collective choices. You talk things through and then you decide. The challenges of the endless search for food often posed alternatives. Some groups will have made a more conservative choice: stay where you are, carry on as before, hope for the best. Others will have been more enterprising, perhaps moving into unknown territory, trying new hunting techniques, or linking up with other groups to pool knowledge, resources, and labour.

A dominant characteristic of Homo sapiens, therefore, was an unrivalled ability to meet the demands of diverse and changeable environments. Initially, they would have migrated along resource-rich coastlines and river systems. But they seem soon to have spread into the hinterland; and wherever they went, they adapted and fitted in. In the Arctic, they hunted reindeer; on the frozen plains, mammoth; on the grasslands, wild deer and horses; in the tropics, pigs, monkeys, and lizards.

Toolkits varied with the challenges. Instead of simple handaxes and flakes, they manufactured a range of ‘blades’ – sharp-edged stone tools longer than they were wide which were struck from specially prepared prismatic cores. They also made clothes and shelters as conditions demanded. They used fire for heating, cooking, and protection. And they produced art – paintings and sculptures of the animals they hunted. Above all, they experimented and innovated. Successes were shared and copied. Culture was not static, but changeable and cumulative. Homo sapiens met environmental challenges with new ways of doing things, and the lessons learned became part of a growing store of knowledge and know-how.

Instead of modern humans either evolving biologically or dying out when environmental conditions changed, they found solutions in better shelters, warmer clothes, and sharper tools. Nature and culture interacted, and through this interaction, humans became progressively better at making a living.

In some places, for a while, Homo sapiens coexisted with early humans. Between c. 40,000 and 30,000 BP, Europe was inhabited by both moderns and Neanderthals. There is DNA evidence for some interbreeding – and, by implication, social interaction – but the main story seems to be the slow replacement of one species by the other. The Neanderthals eventually died out because they could neither adapt nor compete as the climate changed, as Homo sapiens populations grew, and as the big game on which all hominids depended were over-hunted.

Stone-tool technology seems to shadow this species displacement. Neanderthal fossils are associated with Mousterian flakes. Cro-Magnon fossils (as Homo sapiens remains are known in European archaeology) are associated with a range of sophisticated Aurignacian blades. The terms reflect two tool-making traditions recognised in the archaeological record. But that is not all. The new culture was diverse and dynamic, producing, in the course of time, spear-throwers, the harpoon, and the bow, and domesticating the dog for use in the hunt. The Neanderthals had been at the top of the food chain, but the new arrivals engaged them in a ‘cultural arms race’ they could not win.

Gough’s Cave in Cheddar Gorge in England is a classic Homo sapiens site. It has yielded human remains, animal bones, thousands of stone tools, and artefacts made of bone and antler. These date to around 14,000 BP and belonged to a community of horse hunters. The cave offered shelter and a vantage point overlooking a gorge through which herds of wild horses and deer regularly passed. Here was a community of Homo sapiens adapted to a very specific ecological niche: a natural funnel on the migration routes of wild animals during the latter part of the last great glaciation.

The period from 2.5 million years ago, when tool-making began, to 10,000 BP is known as the Old Stone Age or Palaeolithic. Its last phase, the Upper Palaeolithic, is the period of Homo sapiens. It represents a revolutionary break with earlier phases. The Upper Palaeolithic Revol...