![]()

1 A world always divided

At the sources of contemporary spatial terminology

Global developmental divisions up to the Industrial Revolution

The world community is a multilevel structure. It is composed of the inhabitants of the Earth as a whole, along with the different kinds of groupings and institutions created by them that occupy different-sized segments of space, and sometimes achieve a global scale. However, this horizontal and vertical stratification of the world community does not lead to its disintegration. It is essentially a global, multilayered social patchwork made up of an infinite number of pieces of matter, sewn together into a whole by different threads at different levels. Above all, however, its unity is assured through being interwoven with a common warp produced by each great breach in the continuity of the historical process. These breaches have radically transformed history and determined the fate of humanity anew, and from them there has inevitably begun ‘a new story dramatically and completely alien to the previous one’ (Cipolla 1964: 29–30).

Throughout the whole history of humankind, there have been, it seems, only two global and universal warps interwoven with which for hundreds (in the first case, even thousands) of years the fate of the world community was determined. The first great warping mill of history was the Agricultural Revolution, and the second was the Industrial Revolution. These were two great milestones on the road of history – times when, as David S. Landes remarked in relation to the Industrial Revolution, ‘the world had slipped its moorings’ (Landes 1998: 192). From this perspective, we can divide the history of the world community into three periods – the first lasting from the emergence of human beings to the Agricultural Revolution, in which the world community and its history remained deeply atomized, in which the lack of a common historical warp constituted a de facto common warp, while the second and third periods were regulated by ‘agricultural warp’ and ‘industrial warp’, respectively.

The Agricultural Revolution wove ‘a new story dramatically and completely alien to the previous one’ (Cipolla 1964: 29–30), involving such phenomena as new methods for acquiring food, the transition to a settled way of life, an increase in population size and density, the accumulation of material goods resulting in inequalities of wealth, the social division of labour, the birth of the state, and the mass extinction of isolated communities in the western hemisphere and the Antipodes after they had come into contact with representatives of farming communities from the Old World who were carrying virulent illnesses contracted in the process of the domestication of animals. Thus, the Agricultural Revolution ruptured irrevocably and dramatically the continuity of development between ‘the cave-man and the builders of the pyramids’ (Cipolla 1964: 30). Similarly, the Industrial Revolution brought in its wake an entire series of diverse and important, sometimes even amazing, consequences (Davies 1996; Landes 1998), opening ‘our two sunny centuries of growth and wealth’ (Appleyard 2005). The Industrial Revolution ruptured the continuity of development between ‘the ancient ploughman and the modern operator of a power station’ (Cipolla 1964: 30). The period between 1870 and 1900,

and more often the still narrower period of fifteen years between 1867 and 1881, saw the appearance of objects regarded by us today as everyday and indispensable, such as the internal combustion engine, telephone, microphone, record player, wireless telegraphy, the light bulb, mechanized public transport, pneumatic tyres, the bicycle, typewriter, daily newspapers with mass circulation, artificial silk and the first synthetic plastic – Bakelite. And although the intensive production of planes only started under the influence of the needs of World War I, in 1903 the Wright brothers had already demonstrated the potential of using the internal combustion engine for air transportation. A contemporary of our times who suddenly went back to 1900 would find themselves in quite familiar conditions in terms of the practical plain of everyday life, but if that person went back to 1870, they would find the differences more striking than the similarities.

(Kopaliński 1993: 304–5)

The Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions were, however, not just the great warping mills of history that created the foundations and structure of the world community and determined its fate in the period from the first to the second revolution, and from the second until today. Each of these great ruptures in the continuity of the processes of development have also been the great looms of history that have woven into the world community the motif of divisions – after all, ‘where there is society, there is also inequality’ (Dahrendorf 2005: 5).

For by far the greater part of the period before the Agricultural Revolution, the world community was extremely atomized and the world was inhabited by small (numbering a few dozen or so) isolated groups of hunters and gatherers who were almost always on the move and permanently at risk of death from starvation (Orłowski 1999; Konarzewski 2005; Tattersall 2008; Orłowski 2010). The key division of a global and developmental character at that time was between ecumene and anecumene. However, in the context of developmental processes and the differentiation they give rise to, this is a deeply imperfect (and, from a contemporary perspective, even fundamentally flawed) division, because it does not take as its starting point communities and places that are, in fact, different in terms of the level of development reached. Instead, it counterposes areas inhabited by humans, hence already having achieved a certain level of development, with virgin uninhabited areas, untouched (at least at that time) by the processes of development. But if the division between ecumene and anecumene ever had any meaning from a developmental point of view, then it was probably so only during the Palaeolithic Age, as for the vast majority of that period, the processes of development in the inhabited part of the world were so extremely slow that practically nothing new appeared. ‘Thus it was a period of enormous stagnation in which everything ran along established lines’ (Orłowski 2010: 44). The most effective survival strategy was to follow the old patterns of safe behaviour handed down through the generations, which created an extremely hostile attitude towards innovations and the inevitable risks they brought. From the present-day perspective, we could even describe the communities of the Palaeolithic Age as ‘underdeveloped’, but, paradoxically, these communities formed en bloc the contemporary ‘pole of development’, from within which, however, certain elements – a number of communities – were at some point finally able to free themselves from the prevailing state of apathy and thus bring an end to that period of global developmental stagnation, in the process building the first real contrasts within the world community in terms of achieved levels of development (Orłowski 2010). The difference between ecumene and anecumene was never smaller than in the Palaeolithic Age, when the mere arrival and functioning of humans in a particular environment was in itself a manifestation of progress. Although it is a very debatable way of presenting the contrast between ‘developed’ and ‘underdeveloped’ areas, there is a certain sense in which we can say that the anecumene were territories characterized by stagnation and underdevelopment. It is worth remembering that Albert O. Hirschman, in a similar context, used the term ‘undeveloped areas’, understanding this as ‘largely unsettled areas’ (Hirschman 1962: 187). So to describe the divide in question, it is legitimate to use concepts based on Hirschman’s term ‘undeveloped areas’, and its opposite, which should not be so much the concept ‘developed areas’ as ‘developing areas’ or, even better, ‘potentially developing areas’.

Of course, it was not the case that during the whole Palaeolithic Age absolutely nothing of any importance occurred in terms of the processes of development. A truly revolutionary achievement of the Palaeolithic Age was the control of fire, which is variously dated as having taken place from about 600,000 to 1 million years ago (Orłowski 2010). Humanity no doubt ‘came into the possession of fire’ by complete accident, particularly as it is believed that the ability to kindle fire was only acquired some 100,000 years ago (Orłowski 2010). The ‘possession’ of fire gave various benefits and advantages – warmth and light, protection against wild animals, the ability to cook food initially by roasting and later by boiling, which, even if only thanks to the wider menu options, could have had a beneficent effect on subsequent human development (Orłowski 2010). Presumably, ‘coming into the possession’ of fire would have given early humans a feeling of superiority over their surroundings and also over other groups of our ancestors who either did not ‘possess’ fire or had ‘lost’ it (Orłowski 2010). ‘Control of fire gave enormous power to human beings enabling them to bring their entire environment into subjection’ (Orłowski 2010: 45). From this, it can be argued that another early global division relating to the level of development achieved was between those groups of humans able to control fire and those who did not possess it, or did not have the ability to use it. Fire, and especially the art of kindling it, was an evident sign of development, and for this reason it would seem that a division on this basis between ‘advanced’ and ‘backward’ communities (these adjectives seem better in this case than ‘developed’ and ‘underdeveloped’) was the first real, substantive global divide in terms of differences in development levels. However, this division, just as the previous one, defeats all attempts at cartographic representation.

Efforts to reconstruct the developmental divisions within the Palaeolithic world are immensely complicated by the fact that for some time Homo sapiens coexisted with Homo neandertalensis until the latter finally became extinct some 40,000 years ago at the hands of the former. The Neanderthals lived from hunting and gathering, they knew how to use and even kindle fire, no doubt used animal skins to protect their bodies from the cold, and practised the ritual burial of the dead (Nowa encyklopedia 1996; Konarzewski 2005; Orłowski 2010). As a result, the boundary lines between groups at different levels of development would have run not just within Homo sapiens (and probably also Homo neandertalensis), but, in addition, similarities in the level of the development reached may have put certain groups of Homo sapiens and Homo neandertalensis together on one ‘pole of development’ in contrast to other more backward groups also representing both species.

There is, however, another innovation that is also worth considering in the context of these early developmental divisions. In the final phase of the Palaeolithic Age, a developmental acceleration took place, bringing with it new tools and new skills (Orłowski 2010). Undoubtedly, the most significant invention of this period was the bow, the first machine in history, which originated in Europe or its immediate vicinity perhaps some 23,000 years ago or more (Orłowski 2010). It has been argued that a possible consequence of this invention was the birth of culture. According to this hypothesis, the bow, which facilitated, and above all accelerated, the obtaining of food, generated free time, which had earlier been virtually non-existent because of the continual need to search for food. To make use of the time gained in this way, the people of that era, accustomed as they were to permanent activity, began to practise art, as evidenced by such phenomena as cave paintings and rock engravings, the earliest of which date back more than 30,000 years (however, it should be noted that this hypothesis is burdened with temporal imprecision) (Orłowski 2010). In this way, another developmental division would have emerged, between communities possessing more complex tools, and thus the free time necessary to create the beginnings of culture, and those that did not benefit from these achievements. This division would seem, for the first time, to fully merit the use of the counterposed terms ‘developed’ and ‘underdeveloped’. It is also worth noting that until the Agricultural Revolution, the ‘bearers’ of levels of development were people only, and not territories (i.e. developmental divisions had a social rather than territorial character) (this also applies to the contrast between ecumene and anecumene discussed earlier), which is hardly surprising given early humanity’s nomadic mode of life.

Nevertheless, it seems that these early divisions, even if they objectively had a global character, were extremely particularistic, in reality functioning only on a local scale, on the level of the social nano-worlds into which the world community at that time was fragmented. We should also realize that in the history of humanity, this situation lasted longer than any other. If we compare what is, for us, the inconceivably long history of humankind with the passing of 12 hours, then the situation described above characterized perhaps up to 11 hours and 59 minutes; the divisions of the world brought about by the Agricultural Revolution lasted no longer than a minute, and the contemporary division of the world, so widely known and discussed, into the prosperous North and poor South has lasted for little more than 0.02 seconds (Konarzewski 2005).

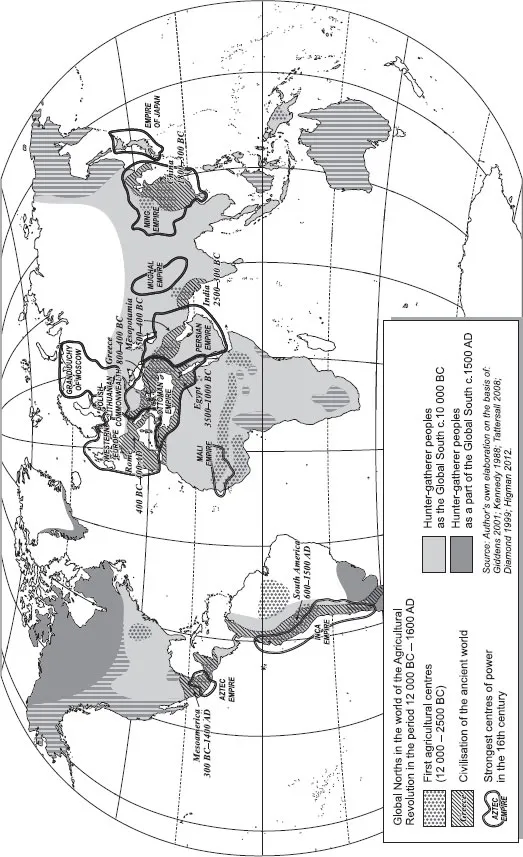

Before the contemporary divide between developed and underdeveloped countries was born out of the Industrial Revolution, for 10,000 years the dominant developmental divisions were those created by the Agricultural Revolution, which had closed the period of early developmental divisions discussed above. The first of these new divisions, in terms both of chronology and its absolutely fundamental significance for the new world formed by the Agricultural Revolution, involved a complete change in the human way of life. The Agricultural Revolution ‘transformed hunters and food-gatherers into farmers and shepherds’ (Cipolla 1964: 31). And so this division was based on the contrast between communities involved in the process of ‘the world slipping from its moorings’ and those that, for various reasons, did not take up this challenge (Figure 1.1). The former (farmers and shepherds) constituted the developed world of their day, while the latter (hunters and gatherers) were the underdeveloped world. In spite of some present-day terminological conventions, the most appropriate designations for the highly developed world of that day would seem to be such terms as ‘developing world’ or ‘emerging world’, something that applies equally to the world of high development that came into existence as a result of the Industrial Revolution. So it is possible even to discern a certain terminological paradox in the fact that today, when we use the concept of ‘developing world’, we do not designate the world that is in the vanguard of the processes of development, but rather the world where crucial segments are sunk in stagnation and backwardness. It is another matter that areas that experienced the new development initiated by the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions over time lost their developmental impetus, and so perhaps the most appropriate method would be to restrict the time frame for using terms with the adjectives ‘developing’ and ‘emerging’ to the earliest, stormiest phases of new development.

Fig. 1.1. The fluid divisions of the agricultural-pastoral world into developed and underdeveloped societies (c. 12 000 BC – 1600 AD)

Easy as it is in relation to this first cardinal division of the world community based on developmental criteria to indicate the principle by which the developed and underdeveloped worlds can be delineated (farmers/non-farmers), depicting this divide on a map is beset by a series of difficulties. The first of these relates to the fragmentary nature of our knowledge about the beginnings of the Agricultural Revolution and therefore uncertainty as to the number, distribution and chronology of its originating areas (Diamond 1999). As a result, there are a number of different, although, of course, to a large degree compatible, lists of areas of developmental acceleration due to the transition from hunting and gathering to farming and livestock husbandry. For example, Jared Diamond (1999) classifies the following areas as highly developed, in the sense we are using, in the period between 8500 and 2500 BC: Southwest Asia (the Middle East, the Fertile Crescent), China, Mesoamerica, the Andes and the eastern part of today’s United States, and also allowed for such a possibility in relation to Amazonia, Sahel, the tropical part of Western Africa, Ethiopia and New Guinea. Alongside this group, he also refers to derivative poles of development – Western Europe, the Indus Lowland and Egypt – where the introduction of alien crop varieties led to the development of local ones. Another author, Ian Tattersall (2008), sketches out a rather more modest picture. Among the centres where farming was initiated some 7,000–12,000 years ago, he includes the Middle East, Sahel, two centres in China, New Guinea, Mesoamerica and the Andes. Yet another picture of areas where the Agricultural Revolution originated some 7,000 years ago is presented by B.W. Higman (2012). In the category of the first agricultural lands, he lists the Fertile Crescent, Egypt, Greece, the Indus Valley, China, New Guinea, Mexico, Ecuador and Peru. All in all, the ‘emerging areas’ categorization for this period is not only multi-elemental (Figure 1.1), but is also, for the moment, still open and potentially incomplete. Another problem is posed by the question of the territorial reach of these ‘poles of development’, both initially and over time.

But these are not the only challenges facing the attempt to delineate the developed and underdeveloped worlds in the era of agricultural-pastoral civilization. A further difficulty is posed by the stretching out of the ‘outbreak’ of the Agricultural Revolution over a period of several thousand years – during the entirety of which there emerged successive, often original, separate and independent ‘poles of development’ dispersed throughout the ecumene. For this reason, unlike in the case of the Industrial Revolution, it is better not to refer to the ‘outbreak’, but rather ‘outbreaks’ of the Agricultural Revolution. As a result, whereas D.S. Landes (1998: 231) could write with reference to the Industrial Revolution that all the ‘examples’ of industrial society, ‘however different, are descended from the common British predecessor’, it is impossible to say the same, even given the subsequent civilizational success of Europe, with reference to the agricultural communities that emerged from the Agricultural Revolution – they sometimes had completely different predecessors. The difficulty in determining the boundaries between the worlds of the then world is therefore also due to the fact that the ‘starting poles’ of the Agricultural Revolution were simply different, sometimes completely. Its beginnings and shape were determined by the natural environment, and nature not only often differed in various settlements, but was also unjust and biased (Diamond 1999). Thus, the centres of the Agricultural Revolution not only frequently had a varying ‘initial capital’, but also a varying ultimate result, with different levels of ‘achieved revenue’ (Diamond 1999). Such a situation caused the developed world ...