![]() Part I

Part I

EU and US Policies and Politics of Immigration Today![]()

1

National Identity and the Challenge of Immigration

Jack Citrin

University of California, Berkeley1

Why does immigration roil the politics of so many countries, even aging societies that need people to help finance the welfare state benefits of their declining populations? Surely a large part of the answer is that immigration brings strangers into “our land,” raising concerns about the erosion of a common national identity. The territorial nation-state remains the dominant political reality of our time; reports of its demise are vastly exaggerated. A nation is a set of people with a common “we-feeling” seeking a state of their own. The attributes giving rise to this sense of common identity may vary, but all nationalist doctrines insist that “the imagined community of the nation must be the primary focus of values, source of legitimacy, and object of loyalty and basis of identity,”2 overriding the claims of minority communities within it.

By changing the ethnic composition of nation-states and increasing cultural diversity, immigration poses the problem of integration, of making newcomers members of the national “team.” The greater the cultural similarity of immigrants to the native population, the less severe this problem may appear, and this has shaped attitudes and policies about who should be allowed to come, but even in the United States, often self-described as a nation of immigrants, public opinion surveys consistently show that Americans favor past immigration over more recent immigration, prefer legal to illegal immigrants, and overwhelmingly reject any conception of multiculturalism that challenges English as the country’s common, unifying language.3

Assimilation, the gradual adoption of prevailing habits and beliefs by newcomers, is one political formula for sustaining social solidarity amid ethnic diversity. Multiculturalism, a policy, conceived in the 1970s, of encouraging the persistence of cultures distinct from the national mainstream, is the alternative embraced by many in both North America and Western Europe. Official support for multiculturalism peaked in the 1980s and 1990s, but there is widespread agreement that the political pendulum has swung toward the opposite pole.4 In 1999, no European country had civic integration (assimilation) policies. By now, language training and civic education are widely adopted as tests not just for citizenship but also for immigration control.5 The leaders of Germany, Britain, and France have publicly denounced multiculturalism as a disaster that threatens their nation’s collective identity and echo the arguments of some academics that a strong overarching national identity is the better approach for integrating immigrants and building a sense of social solidarity in a diverse society.6

This chapter first reviews public opinion data from Europe and North America to show how conceptions of national identity are linked to preferences regarding immigration policy. Then it considers how the extent to which a country adopts multicultural policies is connected both to public attitudes toward immigrants and to trends in conceptions of nationhood. The evidence comes largely from International Social Survey Program (ISSP) data collected in 1995 and 2003 and the European Social Surveys (ESS) collected biennially between 2002 and 2010. Cross-national comparisons show that the contrasting histories of immigration in the United States and in Europe have resulted in different conceptions of where diversity fits into images of the nation. Yet the two forms of national identity often distinguished in the literature—the ethnic and the civic—are widely in evidence in the United States as well as in Europe, and these conceptions relate similarly to individuals’ immigration attitudes in all countries.

Meanings of National Identity

The construct of national identity has cognitive, affective, and normative dimensions. The cognitive facet refers to self-categorization, the answer to the question “who am I?” The affective dimension refers to the strength of one’s identification with one’s country. Patriotism, defined as pride in and love of one’s country, is the standard referent here. Finally, national identities have normative content, by which is meant the criteria that define a nation’s uniqueness. These are the attributes that distinguish “us” from them. In this chapter, I consider both the affective and the normative dimensions, paying particular attention to whether the subjective boundaries of the nation are defined in ethnic, “ascriptive” terms or in civic, “achievable” terms.

Meanings of Multiculturalism

In a descriptive sense, multiculturalism refers to the presence within a political society of many distinct religious, ethnic, or racial groups. Viewed this way, the United States, Canada, and virtually all European nation-states are and will remain multicultural societies. A second meaning of multiculturalism is ideological rather than demographic. In this incarnation, multiculturalism affirms the enduring moral and political significance of ethnic group consciousness and endorses policies designed to support minority ethnicities through special recognition and representation.

Proponents of multiculturalism assert that the welcoming stance adopted toward immigrants, distilled in the phrase “you can be yourselves and still belong here,” will succeed in incorporating newcomers into the political community as loyal citizens. Once this is seen to happen, skeptical natives will no longer view immigrants as a threat to prevailing values and come to accept cultural heterogeneity as compatible with national cohesion. Advocates of assimilation regard these predictions as naïve at best and perverse at worst. In their view, multiculturalism elevates ethnic identification at the expense of commitment to a common democratic culture. Insistence on the value of “difference” provokes resentment that spills over into prejudice as well as an unwillingness to support redistribution measures because they might benefit those who are perceived as undeserving immigrant claimants. Only if immigrant minorities acculturate, advocates of assimilation argue, will they be accepted as full-fledged members of the national community and achieve both social integration and economic advancement.

In exploring the relationships between public opinion about immigration and the presence of multiculturalist policy regimes, I use the Multiculturalism Policy Index for Immigrant Minorities (MCP) developed by Banting and Kymlicka.7 This measure assigns scores to countries by summing the number of the following policies of official recognition and representation for cultural minorities adopted:8

- Constitutional, legal or parliamentary affirmation of multiculturalism;

- The adoption of multiculturalism in the school curriculum;

- Inclusion of ethnic representation/sensitivity in the public media;9

- Exemptions from dress codes or Sunday closing legislation;

- Allowing dual citizenship;

- The funding of ethnic group organizations for cultural activities;

- Funding of bilingual education or mother-tongue instruction; and

- Affirmative action for disadvantaged immigrant groups.

Countries that adopt all these components of the MCP Index receive a total score of 8. Those adopting fewer than three of the eight policies are classified as having “weak” immigrant minority policies. Countries with scores between 3 and 5.5 are categorized as having a “modest” multicultural regime for immigrants, and those with scores between 6 and 8 are “strongly” multiculturalist.

Data from the Multiculturalism Policy Index show that, with the exception of the United States, the “settler” societies in North America and Australasia had more robust multicultural regimes than most European countries. Still, between 1980 and 2000, there was a decided shift toward the adoption of more multicultural policies. Five countries moved from the weak to the modest category and two from modest to strong. No country had a lower MCP score in 2000 than in 1980. For the years between 2000 and 2010, the pattern of change is more mixed. Five countries actually moved in the direction of multiculturalism, as measured by the MCP Index, usually by changes in the content of media and school curricula. Prompted by electoral pressures, the Netherlands alone moved decisively to weaken its policies, which handle the administration of education and welfare policies separately for religious communities (Catholic, Protestant, and then Muslim). Yet, while many multiculturalist policies remained intact between the late 1990s and 2010, most Western European countries adopted civic integration requirements for naturalization, and several were imposing language requirements for new immigrants, policies that reflected a retreat from multiculturalism toward assimilationist views. And clearly the shift in rhetoric and policy was in part a response to the emerging electoral strength of radical-right political parties opposed to immigration.

The Contours of Public Opinion

The United States and Europe approach the dilemmas of immigration policy from radically different historical perspectives, as spelled out by Schain’s chapter in this volume. Despite ambivalent public views, immigration is a fundamental part of America’s founding myth. Most Americans acknowledge that all of “us here now” or our ancestors—Native Americans aside—came from somewhere else. In Europe the story is quite different. Immigration does not figure in the construction of national identities of most nation-states in the ever-expanding European Union. Moreover, unlike the American case, immigrants came to Western Europe more recently, largely in reaction to a series of convulsions in Africa, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East. Against this background, the data from the 2002 ESS and a companion Citizenship, Involvment, Democracy (CID) American survey show more support for cultural diversity in the United States than in European countries.10 This assertion derives from the level of agreement to these statements:

“It is better for a country if almost everyone shares the same customs and traditions.”

“It is better for a country if there are a variety of religions among its people.”

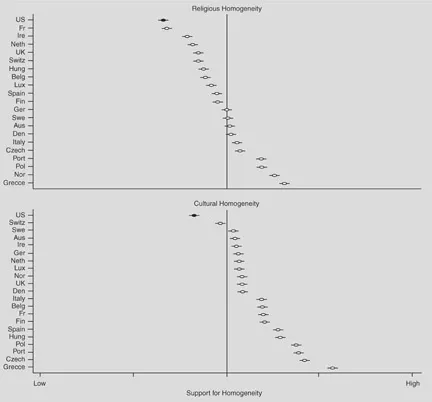

Figure 1.111 presents the country-level means for each item, coded so that high values equal support for homogeneity, along with the 95 percent confidence interval for each country’s mean. The vertical line in each graph indicates the midpoint of the scale, so a country plotted to the left of the line is less committed to cultural homogeneity than a country to the right of the line.

Figure 1.1 shows that countries are relatively evenly distributed between a tendency to support religious homogeneity and a tendency to oppose it. But

Figure 1.1 Beliefs about Societal Homogeneity

the majority in 19 of 21 countries agreed that a country would be better served if everyone shared the same customs and traditions. Only the United States and, to a lesser extent, Sweden fell on the accepting side of the midpoint. It appears that the long history of cultural and ethnic diversity in the United States has produced a distinctive and more favorable orientation toward cultural heterogeneity. This does not, however, extend to support for linguistic diversity. The American public is among the strongest in the conviction that speaking the host country’s language should be a very important qualification for admitting immigrants, and those Americans who value cultural homogeneity are just like their European counterparts in opposing immigration.12

To explore how subjective conceptions of national identity influence immigration attitudes, I rely on questions embedded in the 1995 and 2003 ISSP programs. These surveys include a battery of questions asking respondents how important various criteria are in making someone a “true” national (American, Briton, German, and so forth). In the 2003 survey, the attributes included ancestry, nativity, having lived in the country most of one’s life, being a member of the country’s majority religion, speaking the country’s principal language, having respect for the country’s law and institutions, and “feeling” like a national. (The 1995 ISPP omitted the question about ancestry.)

These attributes of nationhood were chosen in part to capture the ethnic-civic distinction prevalent in the nationalism literature.13 Admittedly, the face validity of some is unclear. For example, neither religion nor language ability is as fixed as ancestry or nativity. Accordingly, Wright and Citrin and Wright pruned these items and created “ascriptive” (ethnic) and “achievable” (civic) national identity indices by summing responses about ancestry and nativity on the one hand and respect for laws and feeling like a national on the other.14

Wright further reports a consistent tendency of ascriptive or ethnic nationalism to be associated with believing tha...