![]()

Skill formation and economic growth

John Benson, Howard Gospel, and Ying Zhu

Introduction and key questions

The rapid economic transformation of Asia over the past several decades, albeit in several and different stages, has led to a surge of research attempting to explain this success and its impact on workers and society. Various explanations have been advanced covering economic, social, political, and cultural factors (see for example: Leipziger 1997; Muqtada and Basu 1997; World Bank 1993, 1995), although the need to consider historical and pre-industrial structures have been well recognized (Green 1999; Whitley 1992). Economic development does, however, depend on the existence of a well-educated society and a well-trained workforce. Surprisingly, however, few systematic and integrated attempts have been made to explore such links in Asia. Where such analyses have been undertaken they have contributed greatly to our overall understanding of the role of training in economic success, although they have generally been limited to one or two successful Asian economies1 or have been only partial in their analysis by focusing primarily on blue-collar production workers (Ashton et al. 1999; Brown et al. 2001; Koike and Inoki 1990).

This economic growth has impacted significantly on labour markets (Benson and Zhu 2011) and the demand for skilled employees and their deployment within organizations. For example it is likely that economies like China and India, which until recently had had a good supply of labour, may in future not be able to meet the demand for skilled labour. Equally, however, older industrialized economies, such as Japan, will also face a labour shortage brought on by the decline in the birth rate, an ageing society, and the changing attitudes towards work of young people. These labour problems will not just be in terms of skills shortages, but also in terms of skills gaps where firms will not be able to meet their future production and quality goals with their existing labour forces. Workforce development and skill formation will thus serve as a major factor in enhancing economic growth and the competitive advantage of firms and economies in Asia.

Despite the importance of workforce development and skill formation to these emerging and established Asian economies, little research on these topics in Asia has been undertaken and no attempt has been made to include the emerging economies of China and India in a comparative analysis. This volume will fill this research gap by exploring the nature, form, and dynamics of workforce development and skill formation in a spread of Asian economies. A number of key themes/questions will underpin the research:

- What are the forms of training and skill development in various Asian economies?

- How does such training take place and who provides it?

- How does training differ across groups, such as managers, professionals, technical staff, white-collar workers, and production workers?

- How does such training and skill development contribute to the economic success of companies and economies?

This book will address these questions by considering skills shortages and skills gaps. It will deal with both initial and ongoing training and the development of skills at various levels (managers, professional and technical staff, white-collar workers, and production workers), primarily in the private sector, although reference to the public sector will be made where appropriate. General education at school and college will be briefly dealt with, as the basis for vocational education and training, and all main forms of training (market-, family-, firm/organization-, association-, state/school/college-based) will be considered.

To provide a wider coverage than past studies, the monograph will focus on a broad range of Asian economies. These include the well-developed economies of Japan, South Korea (hereafter referred to as Korea), and Taiwan, the prosperous city-states of Singapore and Hong Kong, the moderately developed economy of Malaysia, and the rapidly developing transitional economies of China and India. Generally speaking, in the more developed economies, the search for improved efficiency and profitability has meant that many firms (and the economy more widely) have invested heavily, at least in the past, in training. But skills shortages and gaps still remain. In the less-developed economies, skills shortages and gaps increasingly act as a constraint on economic growth and development. Although the book will examine, and provide an assessment of, the current state of training in these Asian economies, including the weaknesses and strengths of their various training approaches, it will also provide an analysis of what the present state of training means for the future development of these economies.

By addressing these issues in such a diverse group of economies we believe this book can make an important contribution to the existing literature and may contribute to a wider reassessment of the role of training in economic development. An in-depth analysis of eight very different Asian economies is clearly beyond the expertise of any one researcher and so we have brought together leading researchers on Asia to prepare the individual case studies. To ensure some consistency between chapters and that the key issues would be addressed we commence the volume with a chapter by Gospel (see Chapter 2) that provides a discussion of the theoretical underpinnings of workforce development and skill formation as well as a broad analytical framework for each ensuing chapter. Readers are thus advised to start with this chapter before consulting any of the chapters that focus on the various economies. Importantly, it sets out in a more complete manner the issues and considerations that need to be taken into account when attempting to understand and assess the level of training in any one economy and the possible future trends and developments.

Structure and framework

The nature of economies' skill formation system was, for many years, overlooked by mainstream economists (Koike and Inoki 1990), notwithstanding the important role in Asian economic development (Green 1999). However, the World Bank (1993) in The Asian Economic Miracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy attributed this success, in significant part, to the rapid creation of human capital. As pointed out by Green (1999: 257) any analysis of various East Asian economies and their successful economic development point to a distinctive set of characteristics such as central control, planning, and stress on values and core skills. On the other hand there are also some important differences in the business structures and systems between Asian economies which have strong historical and institutional foundations (Whitley 1992).

These possible similarities and differences informed our choice of the eight economies in Asia that were chosen to investigate the key questions underpinning this book. In the first instance we wished to have representation of established developed economies such as Japan and Korea along with those economies that are now achieving high levels of economic growth such as China and India. Equally, we wished to have representation of economies that are developed, but smaller economies such as the city-state economies of Singapore and Hong Kong, as well as economies that are in transition from developing to developed status such as Taiwan and Malaysia. One proxy for the level of development is the distribution of employment between the agricultural, industrial, and service sectors. Where employment in the agricultural sector is low it can be reasonably assumed that the level of industrialization and economic development is higher. Equally, advanced developed economies can be characterized in terms of high levels of employment in the services and the tertiary sector. The economies chosen and the employment figures in each sector are presented in Table 1.1.

In the developed economies of Japan and Korea the search for improved efficiency and profitability has meant that many companies invested heavily in offshore production facilities, particularly in China. In these cases, the cost of production was considerably lower and the increasing shortage of skilled workers in the home economy, due to an ageing society and low birth rates, made such a move compelling. These economies still maintained a small agricultural sector mainly for home consumption, but around 70 per cent of workers were now engaged in the service sector. China and India are, in contrast, still strongly agricultural, although more so for India as China has developed a wider

Table 1.1 Employment by sector in the economies studied, 2010 (%) | Economy | Share of employment |

| Agriculture | Industry | Services |

| Japan | 3.9 | 26.2 | 69.8 |

| South Korea | 6.6 | 24.3 | 69.1 |

| Singapore | 0.7 | 30.0 | 69.3 |

| Hong Kong | 0.7 | 12.6 | 86.8 |

| China | 38.1 | 27.8 | 34.1 |

| Taiwan | 5.2 | 35.9 | 58.8 |

| India1 | 57.2 | 12.3 | 30.5 |

| Malaysia | 12.1 | 28.7 | 59.2 |

Sources: see Chapters 3–10.

Notes

1 2008.

2 Rows may not sum to 100% because of rounding.

industrial base. In both economies, however, the service sector represented only about a third of all workers. Singapore and Hong Kong, whilst clearly developed economies, have little in the way of agriculture and in the case of Hong Kong is primarily a service economy with 87 per cent of all workers engaged in this sector. Taiwan and Malaysia have sizeable numbers of workers in each of the three sectors, although nearly 60 per cent of all workers in both economies are now employed in the service sector. As such the eight chosen economies represent the full spectrum of economic development from primarily agricultural, through to strongly industrial, and culminating in highly service oriented.

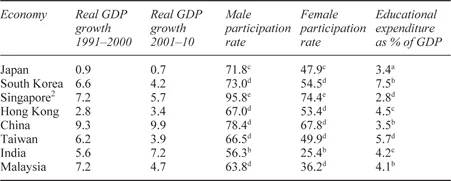

Whilst sectoral employment is a useful way to choose and categorize the eight economies, the chosen Asian economies also vary along some important dimensions such as economic growth, participation, and educational expenditure. These are important variables impacting on skill formation systems and are not necessarily predictable based on the developed/developing economy divide. As can be seen in Table 1.2, the two developing economies, China and India, had significant economic growth in the period 1991 to 2000 and this increased for the period 2001 to 2010. All other economies experienced a fall between these two periods, with Japan's average economic growth for both periods being less than 1 per cent. All the economies considered had lower female participation rates in employment when compared to their male counterparts. India, Malaysia, Japan, and Singapore had the highest discrepancies on this measure whilst the gap was narrowest for China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Korea. Interestingly, the strong economic growth of China created significant work opportunities for women, while the reverse appears to be the case for India. It should be remembered, however, that as a Communist state China had traditionally a stronger emphasis on gender equality in employment. A further useful measure of skill formation is the expenditure on education as measured as a percentage of Gross

Table 1.2 Average real GDP growth, participation rates, and educational attainment

Sources: see Chapters 3–10.

Notes

1 a – 2007; b – 2008; c – 2009; d – 2010; e – 2011.

2 Participation rates for Singapore are for the age range 25–54 years only.

Domestic Production (GDP). Using this measure Korea and Taiwan have the highest spending on education, and in both cases this is well above the OECD average.2 All other economies were below the OECD average with Singapore, Japan, and China spending the least amount, at least as a percentage of GDP. Clearly there is no consistent pattern concerning economic growth, participation rates, and expenditure on education which suggests other factors are at work.

Notwithstanding these sectoral and other economic and labour differences each of the eight economies considered in this book have had a different development trajectory and the history and attitudes of national governments to the way workers should be developed and trained have varied considerably. As such, the economies in this volume represent the range of Asian economies that have undertaken, or are going through, significant economic restructuring and transition and the ways they have addressed demand and supply issues relating to labour. As the case study chapters will demonstrate, each economy has a unique story to be told with different ins...