![]()

![]()

8

SEDITIOUS LIBEL, BAD TENDENCIES, AND ALIEN PROVOCATEURS, OH MY!

IF YOU WERE TO ASK MOST AMERICANS: “WHAT'S THE first thing that comes to mind when I say First Amendment?” chances are that the vast majority would respond: “Free speech!”

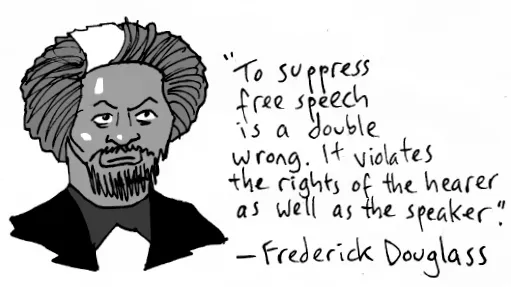

The idea that all people should have an open forum to speak their minds, regardless of how distasteful or offensive their opinions might be, is a core principle of American democracy. The concept has also been embraced far beyond the borders of the United States, widely regarded as a basic human right and enshrined in the UN Universal Declaration of Rights. As we shall see, however, not all speech is absolutely free all of the time, and the idea that speech should be free at all is a relatively new concept, even in the context of American history.

The common law of England contained no freedom of speech protections. Seditious libel, a broad term that included bringing “hatred or contempt” upon the monarch, parliament, or church, was a criminal offense in both England and the colonies. Proof that the statement was true was no defense, and no defamatory intent was required; simply proving that the libelous statement had been intentionally published was enough to warrant a guilty verdict. Using the monarch's name in defamatory or insulting terms, and even nonverbal actions such as urinating or defecating on a picture of the royal person (such things happened!), constituted the crime of lèse-majesté. Until the early 18th century, publishers were required to obtain a government license in order to print their fare.

Newspapers were a constant source of tension between American colonists and British authorities. Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick, the first American newspaper, appeared in Boston in 1690 and was shut down almost immediately for having the temerity to criticize the government without a proper license. James Franklin, the brother of Benjamin Franklin, was imprisoned for a time and had his paper, The New-England Courant, shut down in 1726 for publishing seditious libel. The most famous case, however, was the 1735 libel trial of The New York Weekly Journal publisher John Peter Zenger.

Zenger was arrested and brought up on the charge of seditious libel for printing editorials that criticized the conduct of the governor-general of the Province of New York, William Cosby. (Yes, the royal governor of New York was named Bill Cosby). Zenger's lawyers argued that truth should be a defense to the charge of seditious libel; when the judge overruled them, they urged the jury to disregard the law and acquit their client. After deliberating for less than ten minutes, the jury returned a not-guilty verdict in one of the first examples of blatant jury nullification in American history. Although the case carried no precedential value and newspaper censorship continued unabated throughout the colonial period and beyond, its underlying premises—the right to free speech and the notion that the truth is a defense to libel—eventually won the day.

Even passage of the First Amendment did not end government attempts to limit speech rights in America. Perhaps the single greatest example is the Alien and Sedition Acts, signed into law by President John Adams in 1798. This series of measures made it a federal crime to publish “false, scandalous, and malicious writing or writings against the Government of the United States, or either House of [Congress], or the President, with intent to defame [them] . . . or to stir up sedition within the United States.” The laws were passed as an emergency measure during the “Quasi War” between the United States and France following the French Revolution; fear of French agents infiltrating the country in order to agitate and provoke unrest was rampant. Newly elected President Thomas Jefferson allowed most of the Alien and Sedition acts to expire in 1800, but one section remained on the books and is technically still there today. Called the Alien Enemies Act, this measure was the basis for press censorship during World War I and Japanese internment during World War II.

The Supreme Court never ruled on the constitutionality of the Alien and Sedition Acts, and government censorship continued unabated throughout the 19th century. During the 1830s and 1840s, the U.S. House of Representatives operated under a series of “gag rule” resolutions that forbade members from discussing slavery or bringing up petitions that had anything to do with abolishing or restricting the practice. A number of states passed anti-literacy laws that prohibited black people from being taught how to read and write or being allowed to speak publicly. Many Southern states also criminalized the publication and dissemination of abolitionist literature. Even passage of the Fourteenth Amendment after the Civil War did little to advance the idea that free speech is a constitutionally protected right for everyone throughout the United States. It would not be until the early 20th century and the outbreak of World War I that the Supreme Court finally stepped in.

![]()

9

CLEAR AND PRESENT DANGER (WITHOUT TOM CLANCY OR HARRISON FORD)

CONGRESS PASSED THE ESPIONAGE ACT OF 1917 AT the urging of President Woodrow Wilson upon the United States' entry into World War I. The Espionage Act made it a federal crime to convey false reports, attempt to cause insubordination or refusal of duty in the armed forces, or “willfully obstruct the recruiting or enlistment service of the United States.” This legislation was amended the following year by the Sedition Act, which significantly expanded the scope of the crime to include the use of “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” about the U.S. government, flag, or armed forces, or to “willfully advocate, teach, defend, or suggest” anything that might favor the cause of an enemy nation in wartime.

The Espionage and Sedition Acts were far from toothless warnings to potential dissidents or ways to rally a divided public around the flag. More than 2,000 people would be convicted of violating these laws, and many served lengthy prison sentences. In 1919, the Supreme Court agreed to hear a handful of cases challenging the constitutionality of the acts, the most famous of which were Schenck v. United States and Abrams v. United States.

Schenck involved a challenge to the Espionage Act by two men who were convicted of illegally distributing pamphlets to new draftees that described conscription as being akin to slavery, urging draftees “not [to] submit to intimidation” and to “Assert Your Rights.” A unanimous Supreme Court voted to uphold their convictions, finding that the free speech restrictions in the Espionage Act did not violate the First Amendment. Even if you had never read a Supreme Court decision before, you've almost certainly heard some of the highly quotable language used in the majority decision by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes:

The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic. . . . [T]he question in every case is whether the words are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree.

Holmes's opinion continued with some cryptic remarks suggesting that the Court might have taken a different approach if the same restrictions had applied in peacetime. For example, “When a nation is at war many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right.”

The Supreme Court unanimously affirmed two more convictions under the Espionage Act that same year, using the reasoning outlined in Schenck. Yet when it took up Abrams v. United States, its final Espionage Act case of the term, something strange happened. Justice Holmes appeared to have second thoughts about the broad scope of speech criminalization he had allowed in Schenck.

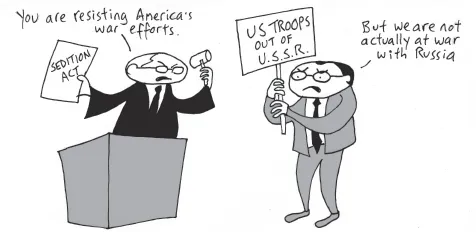

The facts in Abrams were slightly different than in the other cases. The Espionage and Sedition Acts specifically criminalized acts of resistance related to the war effort against the German Empire, but the defendants in Abrams were convicted of distributing pamphlets protesting U.S. military intervention against the Bolsheviks during the Russian Revolution. A seven-justice majority summarily upheld the convictions, but Justices Holmes and Louis Brandeis thought the Court had finally gone too far.

Holmes broke from his prior reasoning to deliver one of the most passionate defenses of the First Amendment in Supreme Court history. While he didn't argue for a reversal of Schenck, which he called “rightly decided,” everything in his dissent slams the actions of the government. It was as if Justice Holmes had reluctantly allowed the government to criminalize certain speech as a wartime measure (Lincoln had done the same, and Holmes might have been sympathetic as a Civil War veteran) but was disappointed when it abused that power. Now Holmes defined clear and present danger more precisely as “danger of immediate evil or an intent to bring it about.” Thus, he wrote, Congress cannot forbid any “silly leaflet by an unknown man” that expresses opinions it happens to disagree with. The purpose of the First Amendment is to allow for the free exchange of ideas, since:

the best test of truth [is] the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.... That at any rate is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all...