![]()

PART ONE

Characters

![]()

1

Mr. Maxwell and Me

It Was the Mid-60’s, and She Was the Dutiful Secretary

of an Esteemed Editor at The New Yorker.

In a Few Short Years the World Changed,

and She Was the One in the Editor’s Chair.

FRANCES KIERNAN

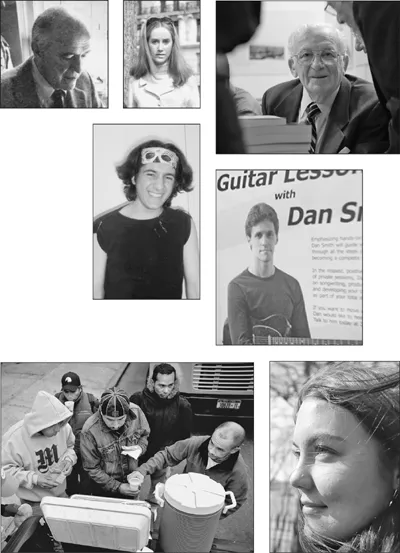

William Maxwell (Anthony Loew/“Over by the River and Other Stories,” Knopf, 1977)

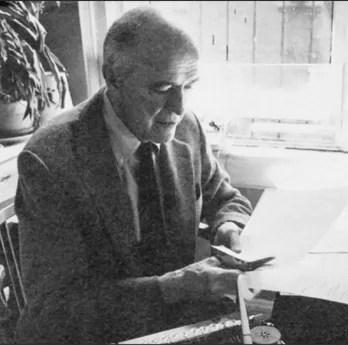

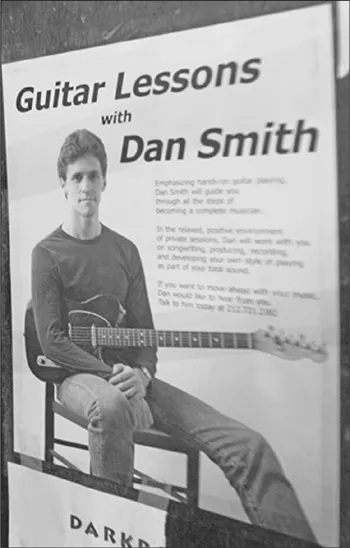

The author on Riverside Drive in 1967. (Courtesy of the author)

IN December 1966, long before secretaries were called assistants, I began working for William Maxwell, a New Yorker editor much admired for his own novels and stories as well as his talent for bringing out the best in his writers. Now, four years after his death, he is revered not only for his literary gifts but also for his generous spirit and great aptitude for friendship, two qualities not easy to come by in the world of New York letters. “A William Maxwell Portrait (Memories and Appreciations),” a collection of essays by fellow writers that will be published this month by W. W. Norton, makes much of this point.

What I saw the first day I was ushered into Mr. Maxwell’s office was a middle-aged man whose face was utterly unremarkable save for brown eyes that seemed to take in everything. I saw him as old, although in fact he was in his 50’s. I had no idea who he was. All I knew was that he, along with Roger Angell, was the editor I’d be working for.

That December, the Vietnam War was heating up, and the women’s movement had yet to catch fire. I was 21, with a degree in English literature from Barnard, and had been earning $90 a week as The New Yorker’s 20th-floor receptionist.

My pay was not unusual for a young woman with a liberal arts degree who could type reasonably well. I had been warned that receptionists and secretaries did not go on to more glamorous jobs at The New Yorker, but I was engaged to marry a young doctor, and after a few years I planned to retire anyway. I think, in fact, that I was promoted from receptionist to secretary as a sort of engagement present.

William Maxwell’s office was at the north end of the 20th floor in the magazine’s old building on West 43rd Street, just off Fifth Avenue. It was large enough to easily accommodate an old-fashioned desk, a long library table, several chairs and a couch covered in beige ticking.

The secretary I was replacing was retiring to the suburbs with her new husband, the way I was planning to retire one day. Her cramped office served as an anteroom to Mr. Maxwell’s. In one corner were a couple of wire baskets overflowing with manuscripts. Above the desk was a shelf with a dictionary, a thesaurus, some packets of restaurant sugar, an electric kettle, a stack of blue and white cups and saucers, a tin of shortbread biscuits and a box of Twinings English Breakfast tea.

Official hours were 10 to 6. Often Mr. Maxwell was at his desk by the time I arrived, and always his desk was piled high with manuscripts, galleys and letters waiting to be answered. At noon he headed off for a quick lunch at the Century Club, two doors down the street. By 12:30 he was back again. From 12:30 to 2, he napped on his couch, during which time I was free to do whatever I wanted. Mostly, I went shopping.

Ordinarily the door to Mr. Maxwell’s office was open by 2. If it remained shut, it was my duty to knock. My next task was to make tea, which was served to him and any visitors he might have, with the tea bag still in its cup and two shortbread biscuits. It never occurred to me to resent this part of my job. If pressed, I would have said that I could happily work for William Maxwell forever.

That June, my two bosses joined forces and bought me a wedding gift from Tiffany’s. By fall, however, my new husband had been drafted and sent to a base in California. There was no way I could stay behind. After enduring 23 months of Tupperware parties and friends’ baby showers, I returned to find that by some miracle my old job was once again vacant. The secretary who had replaced me had gone back to school. I, too, would be going to school, but only two nights a week, with the hope of earning a graduate degree in English.

For two years Mr. Maxwell and I jogged along nicely. By example, he taught me what it meant to write a good sentence and to edit with a light pencil. He also taught me that a gentle manner does not necessarily imply weakness. The only part of my job I found burdensome was keeping track of half the unsolicited fiction, carefully noting each story’s arrival and departure in a black loose-leaf notebook. Submissions were sorted by the author’s last name; I had A to K. After the reader who took care of my half of the alphabet was let go for reasons of economy, I sometimes had up to four overflowing wire baskets in my office.

By 1972 my attitude toward being a secretary was changing. Although I had mixed feelings about the women’s movement, I was hardly indifferent to its demands for equal work for equal pay. My best friend had become a radiologist. All the young women who had arrived at the magazine with me had long since left for better jobs elsewhere.

FINALLY, one Monday morning, I arrived at work to learn that a fiction secretary down the hall, a woman younger than I, was being promoted to a job in the checking department. I had no desire to follow in her footsteps. But that afternoon, as the clock approached 6, I got up my courage and ventured into Mr. Maxwell’s to ask if perhaps I could help with the unsolicited reading, at least until the reader who was doing double duty got caught up. He paused for a moment, then replied, “I don’t see why not.”

Over the next few weeks I found one publishable story and then another. Any story that was actually taken, I was allowed to edit, with Mr. Maxwell’s assistance. Soon I was passing along promising writers to Mr. Angell as well.

As far as I was concerned, this state of affairs could have continued indefinitely. The day came, though, when the magazine’s vice president insisted that my two bosses go to William Shawn, The New Yorker’s editor, and make my de facto position official. My guess is he thought that would put a stop to what was going on before other secretaries got ideas.

An appointment with Mr. Shawn was set up; a meeting took place; and when Mr. Maxwell and Mr. Angell returned half an hour later, both men were shaking their heads. Anticipating their arguments, Mr. Shawn had announced that he saw no need to hire a second reader. Instead, he proposed making me an editor. While I was being trained for this new position, I would continue to read half the unsolicited fiction.

But there was one last question Mr. Shawn had insisted they ask. Both men looked embarrassed; clearly they knew better. Did I plan on having a baby soon? Not so far as I knew, I said.

Where I had least expected it, I had found a job with a future. The trouble was, Mr. Shawn was insisting I move down the hall to an office of my own. He had a point. No editor could possibly work as another editor’s secretary. Of course I would still be seeing Mr. Maxwell. I could even buy my own tin of shortbread biscuits. But I was going to have to give up the electric kettle and the ticking-covered couch.

August 1, 2004

![]()

2

Strumming toward Self-Awareness

For Years, She Had Seen the Fliers Promoting His Lessons.

Then She Inherited a Guitar and Gave Him a Try. Once.

LAURA LONGHINE

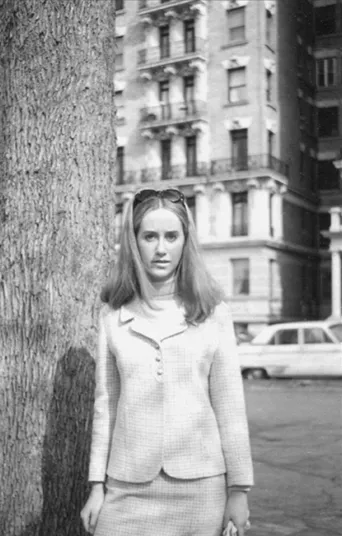

An advertisement filled with promise. (Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times)

IN a sense, Dan Smith had been promising to teach me guitar for years. His fliers, adorned with the photo of a skinny, serious-looking young man holding an electric guitar, said it in bold capital letters: “DAN SMITH WILL TEACH YOU GUITAR.”

I noticed a flier taped to the wall of the bodega near my first Manhattan apartment, on the Upper West Side. Over the next few years, I found them everywhere—on community bulletin boards, in restaurant entryways, on the sides of phone booths. A friend told me she once saw a whole wall of them, next to a shoe repair store.

I always had vague dreams of playing the guitar (who hasn’t?), strumming away in my room and belting out throaty old heartbreaker ballads. Guitar fit very well with a certain romanticized vision of myself: lonely but appealingly sad, artsy and deep.

I didn’t really have the voice to become a traveling folk singer, though. More to the point, I didn’t have a guitar. So when I passed Dan Smith on the way to buy milk or cigarettes, I’d wonder briefly about him, idly imagine taking lessons someday, and move on.

Then my best friend moved to Los Angeles and, having long listened to my abstract longings for a guitar, left me hers. That changed everything. When someone gives you a guitar, you must learn to play it.

I had never bothered to take down Dan Smith’s number, but once I made up my mind to call him, I saw a flier a few days later, in an Upper East Side doorway. “If you want to move ahead with your music,” it said, “Dan would like to hear from you.”

Taking guitar lessons from Dan Smith is like getting skin treatment from Dr. Zizmor; both are legendary self-promoters. So I set up an introductory lesson, even though Dan Smith, who speaks in a friendly but formal way that exactly matches what you’d expect from his picture, tells me he charges $100 an hour, almost what I earn in a day.

One chilly January evening I make my way to his apartment on the Upper West Side. In the lobby, a doorman directs me to an elevator at the end of the hall, past curving marble staircases. On the sixth floor I step out and am glancing around when I hear someone behind me. “Laura?” It’s Dan Smith, leaning out of his doorway, an oddly familiar face. We shake hands.

In his living room, he tells me to take a seat and starts asking me questions.

What do I do? What are my plans for myself? When I tell him I’m a fact-checker (adding, quickly, that I’m also a writer), he asks where I want to go with that. I mumble something about wanting to be an editor, which doesn’t make much sense. I find myself telling him that I am about to move in with my boyfriend, and then I wonder why I am telling him this. Dan Smith takes it all in with nods and reassuring repetitions of, “Sure, sure.”

He asks me why I called him, and when I tell him I’ve been seeing his fliers for years, he straightens up. “Where?” he asks.

“All over,” I say.

He grins. “That’s the idea.”

He had told me not to bring a guitar—I could play his—but asks about mine. Is it nylon or steel strings? I have no idea. I can’t even remember the brand. “It’s from the Matt Umanov Guitar Store,” I offer, silently berating myself for arriving at my $100 lesson so woefully unprepared.

He hands me a Yamaha, and takes a Fender Stratocaster for himself. We go over tuning. “Don’t worry if you don’t remember everything,” he says. “You’ll kind of get it by osmosis.”

In our phone conversation he had asked me what kind of music I liked, and I had mentioned Bob Dylan. So our first song will be “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” which has only three chords: G, D, and A minor.

Piece of cake. He tells me where to put my fingers for a G chord. But somehow, my fingers do not seem to stretch the way his do. It also quickly becomes apparent that my fingernails are getting in the way.

“It’s completely up to you,” he says, “but I do have nail clippers.”

He washes a pair of clippers and brings them over with a small waste basket. As I trim my nails, he plays the song, strumming the chords on his Stratocaster and singing. After his rendition, we listen to Bob Dylan’s rendition. Then I try again.

He tells me to relax my pinky, which is sticking into the air, twisted and tense. I try to relax it, while keeping my other fingers on the appropriate strings. It does not relax. With each chord, I send my fingers conscious commands. It’s like having to tell your legs to walk.

Miraculously, in a matter of 10 minutes, I improve markedly. Occasionally real, right notes come out of the guitar. I decide that Dan Smith is an excellent teacher. I should take one more lesson. Maybe two. Then he lays out the rules.

YOU must pay your $100 in cash, at the beginning of each lesson, and take a lesson of an hour or more every week. If you cancel, you must still pay for that time, unless you can successfully reschedule. He concludes by saying, in his quiet, gentle voice: “I think we can work together. What do you think?”

I explain, awkwardly, what I’ve already explained on the phone, that I can only afford a couple of lessons just now. “I’d like to take at least another lesson or two,” I say. “But I’m going to San Francisco next week.”

“Why?”

“Well I have friends there, and there was a cheap airfare.”

Dan Smith nods, and I immediately regret my revelation. I know what he’s thinking. I can afford to fly to California on an apparent whim, but I can’t afford guitar lessons?

“You have to think about how guitar fits into your life,” he says. “Some people have a lot going on, and there’s just no room for it.

“I’m not saying you’re one of those people,” he adds quickly.

No. I do not want to be “one of those people.” Those sad dilettantes.

We try to schedule something for the following week, but ...