![]()

PART I

NEED

![]()

1

Engineering Masculinity

Veterans and Prosthetics after World War Two

David Serlin

THE EVENTS OF World War Two straddled an uncomfortably unstable period in United States history between the desperate 1930s and the arrogant 1950s. Before the booming economy and unbridled prosperity normally associated with the mid-1950s Pax Americana, many Americans spent the first years of the postwar period recovering slowly from the disruption that wartime had generated in their daily lives.1 The historian William Graebner has called the decade of the 1940s a “culture of contingency,” a time when the chaos of daily life fueled social awkwardness in the face of mass death and destruction.2 While this culture of contingency undoubtedly existed in earlier periods, especially right after World War One, no previous war had called upon so many mental and material resources to create so much technological power capable of so much death. Writing in the late 1950s, Norman Mailer accurately described the previous decade’s sense of contingency as a form of existential anxiety: “Probably, we will never be able to determine the psychic havoc of the concentration camps and the atom bomb upon the unconscious mind of almost everyone alive in these years.”3 To a large degree, this sense of contingency or uncertainty experienced by survivors of the concentration camps and Hiroshima and Nagasaki was shared in the United States by the thousands of wounded, disfigured, and traumatized war veterans returning to civilian life after 1945.

Many disabled veterans who returned home after wartime service were amputees and, in many cases, also prosthesis wearers who worked hard to integrate these new artificial body parts into their civilian lives. One of the foremost concerns of the era was what effect trauma and disability would have on veterans’ sense of self-worth, especially in a competitive economy defined by able-bodied men. Social workers, advice columnists, physical therapists, and policy makers during and after World War Two turned their attention to the perceived crisis of the American veteran, much as they had done after the Great War some thirty years earlier. As Susan Hartmann has written, “By 1944, as public attention began to focus on the postwar period, large numbers of writers and speakers … awakened readers to the social problems of demobilization, described the specific adjustments facing ex-servicemen, and prescribed appropriate behavior and attitudes for civilians.”4

For many, the return of tens of thousands of male amputees and prosthesis wearers signaled an altogether different kind of social response. In the 1930s, conservative critics had already sounded a note of fear over what they perceived to be the erosion of masculinity among American men during the work shortages of the Great Depression. Similar anxieties about American manhood crystallized after the war effort began in 1941 with the new sexual divisions of labor that occurred on the civilian home front. The mobilization of hundreds of thousands of women in the wartime labor force, in combination with the prolonged absence of men from traditional positions of familial and community authority, gave a new shape to civilian domestic culture. In the best-selling Generation of Vipers (1942), for example, Philip Wylie coined the phrase “Momism” to describe what he perceived to be the emasculating effects of “aggressive” mothers and wives on the behavior of passive husbands and sons. Veterans of the war came back to a country where, among other changes they encountered, gender roles had been turned upside down. How, then, did postwar society make sense of veterans and their prostheses, given contemporary hostilities toward “aggressive” women, and given the cultural mandate to readjust veterans to become physically and psychologically “whole” men, made to assume the idealized stature of “real” American men?

This essay explores the significance of prostheses during the late 1940s and early 1950s in the context of the emphasis that postwar U.S. society placed on certain normative models of masculinity. In particular, the essay examines the design and representation of post–World War Two prostheses developed for veterans as neglected components of the historical reconstruction of gender roles and heterosexual male archetypes in early Cold War culture. Like artificial body parts created for victims of war and industrial accidents after the Civil War and World War One, prosthetics developed during the 1940s and 1950s were linked explicitly to the fragile politics of labor, employment, and self-worth for disabled veterans.5 But discussions of prosthetics also reflected concomitant social and sexual anxieties that attended the public specter of the damaged male body.

As this essay will argue, the physical design and construction of prostheses help to distinguish the rehabilitation of veterans after World War Two from earlier periods of adjustment for veterans. Prosthetics research and development in the 1940s was catalyzed, to a great extent, by the mystique of scientific progress. The advent of new materials science and new bioengineering principles during the war and the application of these materials and principles to new prosthetic devices helped to transform prosthetics into its own biomedical subdiscipline. The convergence of these two different areas of research—making prostheses as physical objects and designing prosthetics as products of engineering science—offers important insights into the political and cultural dimensions of the early postwar period, especially in light of what we know about the social and economic restructuring of postwar society with the onset of the Cold War. By the mid-1950s the development of new materials and technologies for prostheses had become the consummate marriage of industrial engineering and domestic engineering.

Prostheses designed and built in the 1940s and 1950s were not merely symbolic or abstracted metaphors. For engineers and prosthetists, these artificial parts were biomedical tools designed and used for rehabilitating bodies and social identities. For doctors and patients, prosthetics were powerful anthropomorphic tools that refracted contemporary fantasies about ability and employment, heterosexual masculinity, and American citizenship. I describe prostheses as tools that enable rather than transcend the organic body, showing how they provided the material means through which individuals on both sides of the therapeutic divide imagined and negotiated the boundaries of what it meant to look like and behave as an able-bodied man in mid-twentieth-century American culture.

PATRIOTIC GORE

Long before World War Two ended in August 1945—the month that Japan officially surrendered to the United States after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—images in the mass media of wounded soldiers convalescing or undergoing physical therapy treatments occupied a regular place in news reports and popular entertainment.6 In John Cromwell’s film The Enchanted Cottage (1945), for example, a young soldier played by Robert Young hides from society and his family in a remote honeymoon cottage after wartime injuries damage his handsome face.7 The Enchanted Cottage updated and Americanized the substance of Sir Arthur Wing Pinero’s 1925 play of the same title. Pinero’s drama focused on a British veteran of World War One who symbolized the plight of facially disfigured veterans (sometimes called “les gueules cassés” by their countrymen) who were often considered social outcasts by an insensitive public.8 In the 1945 North American production, as in the original, the cottage protects the mutilated soldier and his homely, unglamorous fiancée from parents and family members who cast aspersions on the couple for their seemingly “abnormal” physical differences. That both the play and film versions perceive her homeliness and his disfigurement as comparable social disabilities is a telling reminder—relevant in 1925, 1945, or 2002—that we must be vigilant in our continued effort to question the social basis of normative standards of appearance and behavior.

Amputees who returned from war to their homes, hometowns, and places of work—if they could find work—often suffered from lack of due respect, despite the best efforts of the federal agencies like the Veterans Administration to promote the needs of the disabled. Physicians, therapists, psychologists, and ordinary citizens alike often regarded veterans as men whose recent amputation was physical proof of emasculation or general incompetence, or else a kind of monstrous defamiliarization of the “normal” male body. Social policy advocates recommended that families and therapists apply positive psychological approaches to the rehabilitation process for amputees.9 Too often, however, such approaches were geared toward making able-bodied people more comfortable with their innate biases so that they could “deal” with the disabled. This seemed to be a more familiar strategy than empowering the disabled themselves. In William Wyler’s Academy Award–winning film The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), for example, real-life war veteran Harold Russell played Homer, a sensitive paraplegic who tries to challenge the stereotype of the ineffectual amputee while he and his loyal girlfriend cope valiantly with his two new splithook, above-the-elbow prosthetic arms. Given the mixed reception of disabled veterans in the public sphere—simultaneous waves of pride and awkwardness—scriptwriters made Homer exhibit tenacious courage and resilience of spirit rather than show evidence of the vulnerability or rage that visited many veteran amputees. As David Gerber has written, “[t]he culture and politics of the 1940s placed considerable pressure on men like Russell to find individual solutions, within a constricted range of emotions, to the problem of bearing a visible disability in a world of able-bodied people.”10 As a result, recurring images of disabled soldiers readjusting to civilian life became positive propaganda that tried to persuade able-bodied Americans that the convalescence of veterans was unproblematic. Such propaganda was to be expected in the patriotic aftermath of World War Two—and not surprising, either, given the War Department’s decision during the early 1940s to expunge all painful images of wounded or dead soldiers from the popular media.11

The U.S. media were instrumental in concocting regular stories about amputees and the triumphant uses of their prostheses. The circulation of such optimistic and unduly cheery narratives of tolerance in the face of adversity implied a direct relationship between physical trauma—and the ability to survive such trauma—and patriotic duty. In the summer of 1944, for example, U.S. audiences were captivated by the story of Jimmy Wilson, an army private who had been the only survivor of a ten-person plane crash in the Pacific Ocean. When he was found forty-four hours later amidst the plane’s wreckage, army doctors were forced to amputate both of Wilson’s arms and legs. After shipping him back to his hometown of Starke, Florida, surgeons outfitted Wilson with new prosthetic arms and legs, and he became a kind of poster boy for the plight of thousands of amputees who faced physical and psychological readjustment upon their imminent return to civilian life. In early 1945, the Philadelphia Inquirer initiated a national campaign to raise money for Wilson. By the end of the war in August, the Inquirer had raised over $50,000, collected from well-known philanthropists and ordinary citizens alike, such as a group of schoolchildren who raised $26 from selling scrap iron.12 By the winter of 1945, Wilson’s trust fund had grown to over $105,000, and he pledged to use the money to get married, buy a house, and study law under the newly signed G.I. Bill. Wilson’s celebrity status as a quadriplegic peaked when he posed with Bess Myerson, Miss America for 1945, in a brand-new Valiant, a car (whose name alone championed Wilson’s patriotic reception) that General Motors designed specifically for above-ankle amputees.13 Wilson learned how to operate the car by manipulating manual gas and brake pedals attached to the car’s steering column. Demand for the Valiant was so great that, in September 1946, Congress allocated funds that provided ten thousand of these automobiles to needy veterans and amputees.14

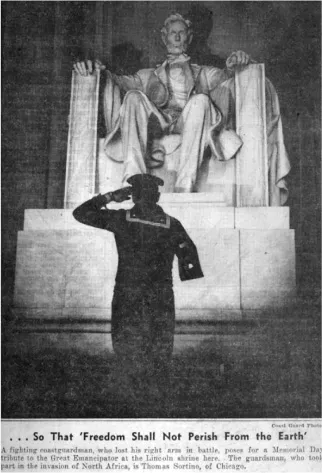

FIG 1.1. This image of war veteran Thomas Sortino of Chicago conjures many historical associations, from the Civil War to World War Two, that link the public appearance of the amputee’s body (especially in such a hallowed space) with patriotic devotion and national identity. From an unknown newspaper clipping (probably late 1945 or early 1946) in the Donald Canham Collection, Otis Historical Archives, courtesy of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, D.C.

If men like Jimmy Wilson were regularly celebrated as heroic and noble, it was because tales of their perseverance and resilience grew proportionately with the fervor of a growing Cold War mentality. In lieu of allowing them to speak for themselves, the media transformed amputees into powerful visual and rhetorical symbols through which war-related disability was identified with unequivocal heroism. In one photographic example published by the Coast Guard press corps in late 1945, the small body of ...