![]() PART I

PART I

DELIBERATION, DECISION, AND ENFORCEMENT![]()

1

DISCLOSURE VERSUS ANONYMITY

IN CAMPAIGN FINANCE

IAN AYRES

INTRODUCTION

About the only campaign finance issue on which there is a strong consensus is the belief that the law should force candidates to disclose the identity of their contributors. The Supreme Court in Buckley v. Valeo has signed off on such regulation as a means of deterring candidates from selling access and influence in return for contributions. Today there are calls for “instantaneous” disclosure via the Internet. Indeed, a growing group of scholars and advocates are coming to believe that mandated disclosure should be the only campaign finance regulation. For example, Representative John Doolittle has proposed “The Citizen Legislature and Political Freedom Act,” which essentially would repeal all limits on political campaign contributions and merely require immediate disclosure by candidates when they do receive contributions.1 This type of “pure disclosure” reform has garnered support from a wide spectrum of both liberals and conservatives—including the CATO Institute, Senator Mitch McConnell, and Kathleen Sullivan.2 People who want to repeal all campaign finance regulation save mandatory disclosure have come to believe that other restrictions are counterproductive because they tend to shift money to less accountable forms of political speech—such as “independent expenditures” and “issue advocacy.”

A set of enduring poetic images for the advocates of mandated disclosure was provided by Justice Brandeis:

Publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases. Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman.

But there exists in our polity a counterimage—the voting booth—that stands against this cult of disclosure. Ballot secrecy was adopted toward the end of the nineteenth century to deter political corruption. “Before this reform, people could buy your vote and hold you to your bargain by watching you at the polling place.”3 Voting booth privacy disrupted the economics of vote buying, making it much more difficult for candidates to buy votes because, at the end of the day, they could never be sure who voted for them.

A similar proanonymity argument can be applied to campaign finance. We might be able to harness similar anonymity benefits by creating a “donation booth”: a screen that forces donors to funnel campaign contributions through blind trusts. Like the voting booth, the donation booth would keep candidates from learning the identity of their supporters. Just as the secret ballot makes it more difficult for candidates to buy votes, mandating anonymous donations through a system of blind trusts might make it harder for candidates to sell access or influence because they would never know which donors had paid the price. Knowledge about whether the other side actually performs his or her promise is an important prerequisite of trade. People—including political candidates—are less likely to deal if they are uncertain whether the other side performs. The secret ballot disrupts vote buying because candidates are uncertain how a citizen actually voted; anonymous donations disrupt influence peddling because candidates are uncertain whether contributors actually contributed.

So which is better: mandated disclosure or mandated anonymity? Each holds the potential for disrupting political corruption. This Article tries to imagine the effects of pure disclosure and anonymity regimes.4 If we were to repeal all contribution or expenditures limitations and were going to regulate only information, which should we prefer? I tentatively argue that mandated anonymity is preferable. It is a less restrictive alternative that is more likely to deter political corruption.

Critics are quick to point out that mandated anonymity is likely to convert some direct contributions into independent, “issue-advocacy” expenditures (where anonymity cannot be required), but they fail to see that mandated disclosure, if it were effective in deterring political corruption, would also be likely to shift some direct contributions toward issue ads (where disclosure cannot be required). The simple reason that mandated disclosure is unlikely to hydraulically push money toward issue advocacy is that disclosing the identity of donors deters very little corruption. Disclosure regimes may make us feel good about ourselves but they probably do not produce very different results than a true laissez-faire regime, where contributors have complete freedom to remain anonymous or to disclose their identity to the candidate and/or the public. Thus, while the Article nominally confronts the choice between mandated anonymity and mandated disclosure, in most cases this is essentially the same as a choice between mandated anonymity and informational laissezfaire. At the end of the day, reasonable people could disfavor mandated anonymity—for example, because of the predictable shift of resources toward less accountable independent issue advocacy—but they should not particularly favor mandated disclosure because it generates substantial benefits beyond a regime that declined to mandate either disclosure or anonymity.

Several states have already experimented with prohibiting judicial candidates from learning who donates to their (re)election campaigns.5 The rationale, of course, is that judges do not need to know the identity of their donors: Judicial decisions should be based on cases’ merits, not contributors’ money. But there is no good reason that legislators or the executive need to know the identity of their donors. An individual’s power to influence government should not turn on personal wealth. Small donors are already effectively anonymous because $100 is not going to buy very much face time with the President. Mandating anonymity is likely to level the influence playing field by making small contributions count for relatively more. Anonymous donors can still signal the intensity of their preferences by marching on Washington—barefoot, if need be.

In what has become a postelection ritual, politicians wring their hands about the problem of campaign donors buying unwarranted “access.” Candidates assert that contributions do not affect their political positions. Nonetheless, the suspicion that “access” leads to corruption persists. If candidates really want to stop themselves from selling influence or access, they should forgo finding out the identity of their contributors.

The idea of mandating anonymity at first strikes many readers as a radical and dangerous departure from the current norm of disclosure. The metaphors of “sunshine” and “open air” are currently very powerful. But to assess the anonymity idea fairly, it is necessary to free ourselves from what might be little more than the happenstance of history. The public ballot was similarly accepted as a natural and necessary part of democracy for roughly half of our nation’s history. This system produced “the common spectacle of lines of persons being marched to the polls holding their colored ballots above their heads to show that they were observing orders or fulfilling promises.”6 These spectacles put such pressure on the disclosure norm that, ultimately, the secret “Australian ballot” caught on and spread like wildfire at the end of the nineteenth century.7 Readers need to consider whether the current spectacle of campaign corruption might be sufficient to overturn our deeply ingrained disclosure norm.

This Article is divided into three parts. Part I compares how mandated anonymity and disclosure regimes might disrupt the market for political influence. Part II then describes in more detail how a system of mandated anonymity might operate. To avoid the “nirvana fallacy” of comparing an idealized reform to a real-world market failure, this part assesses whether the private efforts to evade anonymity—by means of “independent expenditures” or “issue advocacy”—undermine the usefulness of the proposal. Part III argues that mandated anonymity is clearly constitutional. Indeed, appreciating the possibility of anonymity may even undermine Buckley v. Valeo’s conclusion that mandated disclosure is constitutional.

I. MITIGATING THE PROBLEMS OF

POLITICAL CORRUPTION

The corrupting influence of campaign contributions has been a central concern of finance reform.8 The notion that wealthy donors are able to purchase political access or influence is antithetical to our ideal of equal citizenship.9 As Cass Sunstein has observed, “[T]here is no good reason to allow disparities in wealth to be translated into disparities in political power. A well-functioning democracy distinguishes between market processes of purchase and sale on the one hand and political processes of voting and reason-giving on the other.”10 Bruce Ackerman also advocates separating market and political processes: “A democratic market society must confront a basic tension between its ideal of equal citizenship and the reality of market inequality. It does so by drawing a line, marking a political sphere within which the power relationships of the market are kept under democratic control.”11 The most popular reforms for decoupling these spheres operate by regulating money: They either limit the amount that donors can give or they limit the amount that candidates can spend.

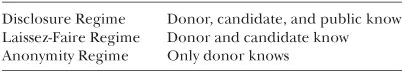

TABLE 1. THREE INFORMATIONAL REGIMES

But there is another way to decouple private wealth from public power. Instead of limiting money, we might limit information. Since Watergate, the only informational reforms have been those that have increased the amount of mandated disclosure. Discussions of disclosure often assume that we must choose between a world in which everyone knows of a gift (the disclosure regime) and a world in which only a donor and her candidate know the source of a gift (the laissez-faire regime). But as shown in Table I, this analysis overlooks the possibility of moving toward a world in which only the donor knows about a gift. In fact, there are several different continua of possible informational regulations. For example, we could require the blind trusts that received a candidate’s contributions to publicly disclose the identity of all donors but not the amounts that the individuals gave.12 For specificity, I will image a “mandated anonymity” regime where the donor has the option of remaining completely anonymous or having the blind trust verify publicly that she gave up to $200. The trust would never disclose whether a donor had given more than $200. It is my thesis that the failure of scholars and courts to consider these alternative informational regimes is largely responsible for the strong consensus in favor of public disclosure.

The impetus for disclosure is that a public armed with knowledge about political contributions will be able to punish candidates who sell their office or who are otherwise inappropriately influenced. It has, however, proved exceedingly difficult to infer inappropriate influence from the mere fact of contributions. Politicians claim they would have acted the same way regardless of whether a questionable contribution had been made. Moreover, we have been unwilling to prohibit selling access (re: face time) in return for contributions. The attorney general has flatly concluded that such quid pro quo agreements are legal.13 And today’s jaded citizenry imposes hardly any electoral punishment on candidates known to have sold political access. In sum, public disclosure produces very little deterrent benefit: types of corruption that can be proved (contributions for access) are legal, and types of corruption that are illegal (contributions for influence) can’t be proved. At most, disclosure deters only the most egregious and express types of influence peddling.

In contrast, a regime of mandated anonymity interferes with an informational prerequisite of corruption. Put simply, it will be more difficult for candidates to sell access or influence if they are unsure whether a donor has paid the price. Of course, much turns on whether government can actually keep candidates uninformed about who donates to their campaigns. But to begin, this section considers what an idealized regime of mandated anonymity—without evasions or substitute speech—can and cannot accomplish.

An idealized donation booth would severely impede quid pro quo corruption, the trading of contributions for political access or influence. This effect would encompass not only explicit trades (donations for nights in the Lincoln bedroom, presidential coffees, legislative activity), but also a large range of implicit deals, including sequential action whereby either the politician or donor “performs” in expectation of subsequent performance by the other side. The Supreme Court’s concern with the corrupting effects of “political debts”14 would also be neutralized by the donation booth for the simple reason that politicians would be unable to determine to whom they were indebted. This rationale was explicitly used to justify a proposed system of anonymous donations to presidential legal defense funds. In 1993, the Office of Government Ethics (“OGE”) reasoned, “Anonymous private paymasters do not have an economic hold on an employee because the employee does not know who the paymasters are. Moreover, the employee has no way to favor the outside anonymous donors.”15

Mandated anonymity could also deter politicians from extorting donations. The popular discussion of quid pro quo corruption focuses solely on campaign contributions in return for legislative favors. In the terminology of public choice theory, donors would be engaged in a kind of “rent seeking.” But there is a radically different kind of quid pro quo corruption. Politicians engage in “rent extraction” when they threaten potential donors with unfavorable treatment unless a sufficiently large contribution is made.16 Rent extraction almost surely explains some of the anomalous patterns of giving—particularly, the “everybody loves a winner” phenomenon. The high level of contributions made to incumbents with safe seats is consistent with rent extraction because incumbents have the greatest ability to extort donations.17 Understanding rent extraction also explains why several corporations have privately agreed not to make soft money contributions.18 Fear of rent extraction may even keep private interest groups from organizing because politicians will have a harder time shaking down an unorganized mass.19 Mandated donor anonymity would allow private interests to organize without fear of being targeted for extortion.

Just as the secret ballot substantially deterred vote buying, mandating secret donations might substantially deter both forms of quid pro quo corruption: rent seeking and rent extraction. There is a lively academic debate about how much current campaign donations are intended to garner access or influence or to avoid unfavorable treatment.20 Since mandated anonymity is better suited than mandated disclosure to deter quid pro quo corruption, an important part of its justification must turn on the extent to which this form of corruption is truly a problem.

However, the problems of “monetary influence corruption” or “inequality” also plague our current system of campaign finance.21 Although mandated anonymity would not eliminate these problems, a regime of mandated anonymity is likely to mitigate these problems much more than a regime of mandated disclosure. Even when politicians don’t condition their behavior on contributions, they may nonetheless expect that taking certain positions will cause donors to give more money. This is the problem of “monetary influence.” And even when wealthy donors don’t expect their giving to change a candidate’s behavior, they may reasonably believe that giving to a candidate with whom they agree will increase that candidate’s chance of (re)election. This at times is referred to as the inequality problem. In the first instance, there is the possibility that a contribution has a corruptive influence on the candidate’s behavior. In the second, even though the candidate’s positions are uncorrupted (read “unchanged”) by the contribution, the contributions of those with disproportionate wealth corrupt the process by increasing the likelihood that positions favored by the wealthy will be disproportionately favored in our political sphere.

Some might argue, however, that monetary influence is not a problem because donors’ willingness to pay usefully informs candidates about the intensity of voter preferences. Yet there is strong consensus from a broad range of scholars that politicians should not choose their policies with an eye toward campaign contributions.22 Not all interest groups can readily organize to compete for candidates’ monetary inter...