![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Religious, Racial, and Ethnic Identities of the New Second Generation

RUSSELL JEUNG, CAROLYN CHEN, AND JERRY Z. PARK

It’s like regardless of your race or background, everybody comes. You see—well, there’s not too many whites, [but] you know, we had that Bosnian guy, he came. And we have some African Americans, we have a whole lot of Arabs and people from the Indian subcontinent. We have an Indonesian guy who comes. … It’s just everybody comes together. We come and pray together, and it’s just awesome. … It’s—we’re all equal, all standing in line together, we’re all praying to the same Lord, and we’re all listening to the same speaker. It’s unreal.

—Shaheed, second-generation Pakistani Muslim, describing how his university’s Muslim Student Association transcends race and ethnicity

I think that Nueva Esperanza is what our people have been looking for, for years. And I think that if these folks stay on track, the Latino community is going to have a voice like never before over the next ten years. I think the black church is organized; I think that African Americans in this country have organized. It’s time for our people to organize! You know, we’re the least respected, least educated, most impoverished, and I think that that season and that age is changing now with organizations such as Nueva Esperanza.

—Pastor Francisco, a second-generation Puerto Rican evangelical, describing how his national organization mobilizes Latino religious leaders

Race and religion matter enormously for the new second generation, the children of post-1965 immigrants. They are negotiating who they are and where they belong in a United States that has transformed with contemporary immigration. In the epigraphs, Shaheed delights in how his Muslim identity transcends ethnic and racial differences; for Pastor Francisco, on the other hand, religion offers a way to mobilize Latino solidarity and organization toward social justice. What accounts for such different manifestations of their religious traditions?

This volume investigates the intersecting relationships between race, ethnicity, and religion in the lives of second-generation Asian Americans and Latinos, examining how faith traditions transform in the American context. The diversity of religious traditions held by Asian Americans and Latinos—including evangelical Protestantism, Catholicism, Buddhism, Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, and ethnic popular religions—provides potential resources for reconfiguring racial and ethnic relations in the United States today. Faith traditions are sources of innovation and self-determination.

This book engages with the influential thesis on religion and ethnicity that social theorist Will Herberg proposed 50 years ago. Building on the traditional view of assimilation at that time, Herberg argued that commitment to national and ethnic heritage would decline for the descendants of immigrants. He went on to argue that religious affiliation—as Protestant, Catholic, or Jew—would become their primary source of social identity in the United States. He explained, “The newcomer is expected to change many things about him as he becomes American—nationality, language, culture. One thing, however, he is not expected to change—and that is his religion. And so it is religion that with the third generation has become the differentiating element and the context of self-identification and social location” (Herberg 1955, 23). Herberg’s theories, however, were based on the experiences of the descendants of European immigrants at a time when mass immigration to the United States had halted for over 30 years. Like other social theorists of the time, Herbert did not account for race in a manner that would be largely taken for granted by observers today. To Herberg, race was less relevant to the immigrants he saw; religion instead constituted their main identity, especially after the first generation. Notably, race was important for black and Asian (then sometimes called “Oriental”) Americans, who sustained a permanent inferior status. Other European-origin Americans who held on to their national (i.e., ethnic) culture risked similar marginalization. But they could maintain their religious identity permanently and without social penalty because Protestantism, Catholicism, and Judaism reflect American “spiritual” values of democracy and the dignity of the individual. Indeed Herberg argued that adherence to other religions such as Buddhism and Islam identified an individual as non-American.

In this volume, we examine religion, race, and ethnicity among Asians and Latinos, the largest ethnic/racial groups among contemporary immigrants to the United States. Much has changed since Herberg penned his treatise. We argue that in light of critical social and demographic changes, ethnicity does not become eclipsed. Instead, the experience of race and ethnicity not only foregrounds but shapes the religious experiences and identities of the new second generation. To answer the questions of “Who am I?” and “To which group do I belong?” the second generation today does not look merely to religion, as Herberg claimed, but to religion, race, and ethnicity simultaneously. The core motivating question for this volume, then, is, How does the second generation negotiate these three different forms of competing and possibly conflicting claims on identity and belonging in America?

Four Trajectories of Race, Religion, and Ethnicity

The second generation may be seen as negotiating race, religion, and ethnicity in four different ways: (1) religious primacy, (2) racialized religion, (3) ethnoreligious hybridization, and (4) familistic traditioning. Latino and Asian American evangelical Christians who belong to multiethnic congregations, Muslims, and Asian American Jews are examples of members of the new second generation who practice religious primacy and prioritize religious identities over all others. For those who practice racialized religion, religion does not transcend race and ethnicity but rather affirms racial boundaries that are a product of the racialized experiences of Asian and Latinos in the United States. Both Latino faith-based organizations and Latino gang ministries are examples of racialized religion. Ethnoreligious hybridization describes the processes by which second-generation groups such as Korean American evangelicals and Filipino Catholics employ multicultural discourse to reinvent religious traditions and to combine ethnic and religious identities. And finally, noncongregational religious and spiritual traditions that are domestic and kin centered fall into the category of familistic traditioning. Practices such as Chinese popular religion, Vietnamese ancestral veneration, and Indian American Hinduism are often not identified as “religions” by practitioners, but they are family traditions that affirm identification with and belonging in an “ethnic” family.

The four religious trajectories of the new second generation are structured by three factors that have emerged since Herberg’s time of writing. First, the racial composition and economic opportunities of the American population have shifted as the new post-1965 immigrants have primarily been people of color. Their assimilation has been segmented, so that they do not necessarily adopt a singular “American Way of Life,” nor do they have equal access to upward mobility, as Herberg described. Second, much of American discourse now embraces a racialized multiculturalism, in which both ethnic and racial identities are valued. Consequently, religious mobilization along these identities has been legitimated and even prized, which Herberg could not have foreseen when he predicted that assimilation must occur exclusively on religious grounds. Finally, the religious landscape in the United States has radically changed, so that the public authority and institutional role of religion in constructing individuals’ and groups’ identities has altered. These socioeconomic and cultural changes thus provide the context for the religions of the new second generation.

The Effect of Race and Class on Religious Identities

With the passage of the 1965 Immigration Act and the 1990 Immigration Act, newcomers from Latin America and Asia have significantly changed the racial make-up of the United States (Rumbaut and Portes 2001). Overall, in the 2010 U.S. Census, Latinos made up 16.3% of the population (50,477,594), and Asian Americans were 4.8% of the population (14,674,252). Their children—the new second generation—are now coming of age and compose significant proportions of America’s youth and emerging adult populations. Their religious socialization and affiliation signal social change unlike any other in this nation’s history. These demographic shifts, in turn, are also shaping the new religious landscape of America (Foley and Hoge 2007; Lorentzen et al. 2009; Min 2010; Raboteau, Dewind, and Alba 2008).

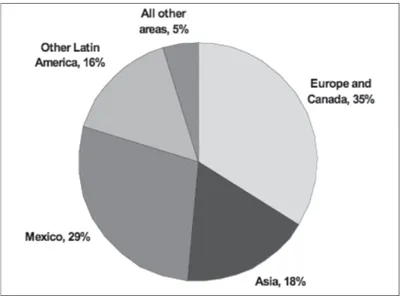

The new second generation, which currently makes up nearly 11% of the U.S. population, is made up of primarily people of color, whose racialization marks them as “ethnic” Americans. Given the current anti-immigrant political context of the United States, their opportunities to assimilate into mainstream American denominations are mixed, at best. As seen in figure 1.1, over half of the new second generation is either Latino or Asian American: 29% of the new second generation is from Mexico, 18% is from Asia, and another 16% is from other countries in Latin America. Members of the second generation who have parents from Europe or Canada make up one-third of this subpopulation. We note that while this latter group is significant in size, its members are generally much older than are the Asian Americans and Latinos in the second generation. According to analyses by the Migration Policy Institute, using data from the Current Population Surveys of 2005–2006, the European- and Canadian-origin second generation has a median age of 54, while the median age of the Mexican-origin second generation is 12 years, of other Latin American origin (13 years), and of Asian origin (16 years)—all below 18. Put differently, the non-European-origin second generation surveyed in 2006 has a median birth year between 1990 and 1994, whereas the European- and Canadian-origin second generation has a median birth year of 1952. We can safely presume that the majority of the members of today’s nonwhite second generation are the children of immigrants who arrived as a result of changes in immigration policy since 1965.

Figure 1.1. Background of the New Second Generation, Current Population Survey, 2006 (Dixon 2006)

Thus, the new second generation will change the racial composition of the United States, as well as its religious landscape. By 2050, Latinos, as the largest minority group in the nation, will compose 29% of the population, and whites will be a minority (Fry 2008). The Asian American population will grow to make up 9% of the U.S. population. Neither white nor black, the racialization and Americanization of Latinos and Asian Americans will chart race relations for decades to come, as they adapt to a globalized, segmented economy in the United States.

Although Herberg argued that religious identity is primary, segmented assimilation theorists privilege the structural factors of race and class in the adaptation of the new second generation. They note that post-1965 immigrants differ from prior groups because the former are nonwhite and incorporated into a more multicultural, racialized society and into a postindustrial, segmented economy (Rumbaut and Portes 2001, 2006; Zhou 2009).

Both race and class prominently structure the religious experiences of the new second generation—not only the context in which individuals live out their religion but also in how theologies, institutional forms, and identities become established. The second generation’s concrete material conditions frame the context in which members produce their theologies, build their congregations, and experience their religious traditions. Globalization and the concomitant restructuring of America’s industrial base have led to an hourglass-shaped economy, with a large pool of service-sector jobs, little union-wage manufacturing work, and increased demand for high-tech professionals. Without the availability of the kind of union-waged jobs that were afforded previous immigrants, the new second generation has much more limited economic opportunities. Many low-income immigrants remain trapped in underclass neighborhoods, and their children may adopt values and practices of oppositional culture. On the other hand, professional immigrants can bypass urban centers and move straight to suburbs with significant concentrations of middle-class racial minorities, or ethnoburbs, where their children can maintain their privilege by attending better schools and utilizing professional ethnic networks.

Members of the new second generation therefore do assimilate but enter a segmented economy in which their opportunities for economic and social integration into the American middle class differ. Recent research shows patterns of segmented assimilation, in which educational attainment and income of the new second generation are shaped by structural factors such as race, class, and ethnic networks (Rumbaut and Portes 2001, 2006; Zhou 2009). Likewise, these structural factors continue to shape the second generation’s religious affiliations in segmented trends.

An explicit comparison of different classes of the Asian American and Latino second generation highlights how segmented assimilation shapes religious traditions. In this volume, both the chapter by Milagros Peña and Edwin I. Hernández and the chapter by Edward Flores analyze how some Latino ministries clearly develop theologies and programs around the impoverished neighborhoods where they are based. As Flores demonstrates, “color-blind racism” has created racial inequalities that are addressed by these Latino ministries. Similarly, the children of Vietnamese refugees in Linda Ho Peché’s chapter and the children of Toisanese working-class parents in Russell Jeung’s chapter do not assimilate into the white middle class and their religions. Instead, they are much more likely to maintain their ethnic popular religious practices than are their Asian American upper-middle-class counterparts.

In fact, middle-class Latinos and Asian Americans have more ethnic options available to them than low-income Latinos and Asian Americans have (Waters 1990). Gerardo Marti in his chapter examines mostly middle-class Latinos, who are able to become “ethnic transcendent” as they enter multiethnic congregations in which their religious identities are primary. The Asian Americans in Sharon Kim and Rebecca Y. Kim’s chapter, as well as those in Jerry Z. Park’s chapter, are also upwardly mobile, but they utilize their class resources in a different trajectory. They choose not to assimilate religiously but instead to hybridize their ethnic and religious identities and to maintain ethnic solidarities. Not only have the racial demographics and economic opportunities of the new second generation shifted, but so has the dominant American discourse on race relations.

Racialized Multiculturalism

In contrast to the triple melting pot that Herberg described in the mid-20th century, American social institutions today may establish contexts in which racial differences and ethnic culture may be prized. Those who favor American multiculturalism not only acknowledge but celebrate ethnic, racial, and religious diversity. The term racialized multiculturalism highlights the twin discourses that now shape the religious trajectories of the new second generation.

Through racialization—the process of categorizing by race or extending racial meanings to practices or groups—the categories of Asian American and Latino have become taken-for-granted communities in the United States (Omi and Winant 1994). The United States employs a multicultural discourse that normalizes five major racial labels: white, black, Hispanic, American Indian, and Asian American (Hollinger 1995). Seen as neither whites nor blacks, post-1965 immigrants from Asia or Latin America face a cultural context that symbolically and structurally minimizes significant political-national differences in favor of these panethnic racial constructions that position them.

Beyond establishing panethnic groupings, racialization also creates a racial hierarchy in the United States, with Asian Americans and Latinos positioned in between African Americans and whites (Bonilla-Silva 2003; C. Kim 2003; Lee, Ramakrishnan, and Ramirez 2007; Light and Bonacich 1991). Because of their physical characteristics, geopolitical positioning, class backgrounds, and historical racial discourses, Latinos and Asian Americans are racialized on a nativist dimension and stand apart from both whites and blacks. Members of the new second generation are often considered outsiders and foreigners. In fact, the process of Americanization and determination of who is considered authentically American requires the creation of a deviant, non-American grouping. In the anti-immigrant sentiment of the times, Latinos and, to a lesser degree, Asian Americans become portrayed as “illegal aliens” and “suspect foreigners.” Thus racially oppressed, the new second generation maintains ethnic and racial groupings out of reactive solidarity, despite the claims of new assimilation theorists (Alba and Nee 2005; Kasinitz et al. 2008).

Asian Americans and Latinos, including those involved with faith-based organizations and congregations, have taken these racial categories and rearticulated them as self-determined, empowered racial identities (Espinosa, Elizondo, and Miranda 2005; Jeung 2005; Park 2008). Religious leaders and institutions have also mobilized around these identities to build their congregations, to relate to other groups, and to engage their sociopolitical environment. Indeed, if the multiculturalist discourse were to be believed, being black, white, Asian, or Latino is as “American” as being Protestant, Catholic, or Jewis...