![]()

Cell Biology and Pathology of Podocytes

Liu Z-H, He JC (eds): Podocytopathy. Contrib Nephrol. Basel, Karger, 2014, vol 183, pp 1-11

DOI: 10.1159/000360503

______________________

Cell Biology of the Podocyte

J. Ashley Jefferson · Stuart J. Shankland

Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Wash., USA

______________________

Abstract

Background: The terminally differentiated and highly specialized glomerular epithelial cells called podocytes function as a major barrier to protein passaging from the intravascular glomerular capillaries to the extravascular urinary space. However, once injured in disease, increased passage of proteins leads to proteinuria, and a decrease in podocyte number underlies progressive glomerular scarring. Summary: Numerous proteins specific to podocytes enable their normal functions, including those that comprise the slit diaphragm to act as a size, charge and shape barrier, a rich actin cytoskeleton that enables mobility, and the production and secretion of growth factors required for normal glomerular endothelial cell health. When injured in podocyte diseases such as focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, minimal change disease, membranous nephropathy, diabetic kidney disease and others, several of these normal functions are disrupted, leading to changes in histological appearance, structure and function. These are typically manifest clinically by proteinuria and a decline in kidney function. Key Messages: Because of podocyte's inability to adequately proliferate, a decline in their number follows when cells undergo apoptosis, detachment, necrosis and altered autophagy in response to injury. This leads to progressive glomerular scarring. These mechanisms will be discussed in this chapter. Alterations in key slit diaphragm proteins lead to proteinuria, which will also be discussed.

© 2014 S. Karger AG, Basel

Podocytes are terminally differentiated epithelial cells lining the outer aspect of the glomerular capillaries. Their complex ultrastructure consists of a cell body, from which extend long branching cellular processes, comprising primary and then secondary processes. These end in foot processes, which attach podocytes to the underlying glomerular basement membrane (GBM). Podocytes serve several critical biological functions. First, highly specialized cell junctions between adjacent foot processes are bridged by slit diaphragms which allow ultrafiltrate to pass but limit the passage of critical proteins such as albumin [1]. They act as a size, shape and charge barrier to the passage of protein from the intravascular compartment of the underlying capillary network to the extravascular urinary space. Second, the rich actin cytoskeleton enables podocytes to actively maintain the integrity of the underlying glomerular capillaries [2]. Third, podocytes make extracellular matrix proteins such as laminin β2 and the collagen α3,α4,α5 (IV) network required for the development of the normal GBM, and likely thereafter, for normal GBM maintenance. Finally, podocytes secrete critical survival factors for neighboring glomerular endothelial cells, such as VEGF and angiopoietin-1 [3]. Following injury in primary glomerular diseases such as focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), membranous nephropathy and minimal change disease [4], as well as secondary glomerular diseases such as diabetic nephropathy, one or more of these biological functions are reduced or absent, leading to the characteristic histological and clinical manifestations described below.

Responses of Podocytes to Injury

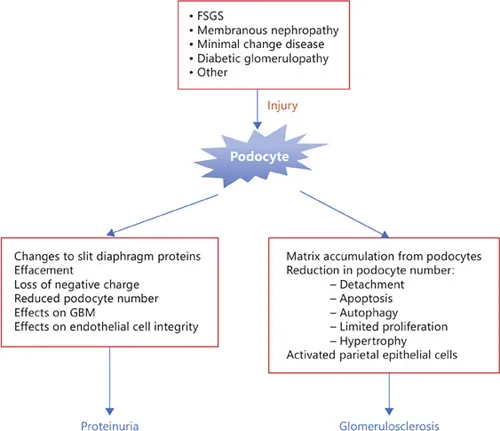

Although each glomerular disease has unique mechanisms by which they induce podocyte injury, there are several common responses to injury that will be discussed below (fig. 1).

Podocyte Injury and Proteinuria

The clinical signature of podocyte injury is proteinuria, predominantly albuminuria. As discussed elsewhere in this series, although the magnitude of proteinuria varies, podocyte diseases must be considered when patients present with nephrotic range proteinuria (≥3.5 g/24 h). Several mechanisms underlie proteinuria following podocyte injury:

(i) Changes in slit diaphragm proteins: Several ‘podocyte-specific’ proteins are concentrated in the slit diaphragm, whose primary function is to form and support the sieve-like structure of this modified tight junction [1]. These filtration slits are 40 nm wide between adjacent processes, slightly smaller than the size of albumin. Nephrin is the protein that forms the major backbone, but requires complexing with several other proteins such as podocin and NEPH for normal function, as well as several adapter proteins such as CD2AP [5]. The slit diaphragm structure is size-selective, although a negative charge might also limit albumin passage. Abnormalities of slit diaphragm proteins can arise from several events in disease. First, a decrease in absolute levels of one or more of these proteins in acquired glomerular diseases disrupts the overall barrier function. Second, mutations in genes encoding nephrin, podocin, TRPC6 or CD2AP occur in several forms of congenital and hereditary glomerular diseases [6]. Third, disease-induced changes in the subcellular location of nephrin or podocin prevent their normal function [7].

Fig. 1. Response to podocyte injury. Several diseases target podocytes, and induce injury. The events leading to proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis are summarized.

(ii) Effacement: The characteristic ultrastructural finding of podocyte injury is called effacement, which is seen on electron microscopy as a flattening of foot processes. This is an active process mediated by changes in the actin cytoskeleton. Effacement leads to distortions and loss of the slit diaphragm impairing its normal barrier and signaling function. See below for more detailed discussion.

(iii) Loss of podocyte negative charge: Podocytes are negatively charged due to anionic proteins such as podocalyxin. Loss of this negative charge, due to alterations in these proteins, limits the charge selective barrier capacity of podocytes.

(iv) Reduced podocyte number: Although reduced podocyte number is typically considered as a major cause of glomerulosclerosis, their absence leads to uncovered areas on the outer aspect of the GBM, through which albumin and other proteins might easily traffic.

(v) Effects on the underlying GBM: The GBM is a critical resistor to the passage of proteins across the glomerular filtration barrier [8]. Injury to podocytes can directly affect the underlying GBM to which these cells attach by several mechanisms. First, injured podocytes produce and secrete extracellular matrix proteins in membranous and diabetic nephropathies, leading to thickening of the GBM. These matrix proteins such as collagen IV, laminin and fibronectin alter the normal matrix composition, leading to enhanced permeability across the GBM. Several cytokines such as TGF-β are responsible for this matrix accumulation [9]. Second, podocytes secrete reactive oxygen species when injured. These have a detergent like action on certain matrix proteins of the adjacent GBM, and create holes in this matrix structure through which albumin can passage [10]. Third, several metalloproteinases such as MMP-9 are released by damaged podocytes and may degrade target matrix proteins [11]. Fourth, podocytes produce heparin sulfate proteoglycan which may contribute to the charge barrier of the GBM.

(vi) Podocyte regulation of endothelial cell integrity: Although podocytes are on the ‘other’ side of the GBM to the innermost glomerular endothelial cells, they secrete critical survival and pro-angiopathic factors for endothelial cells such as VEGF [12] and angiopoietin-1 [13]. A decrease in VEGF secretion following podocyte injury or loss results in endotheliosis and/or endothelial death, which in turn limits their function as a charge barrier to proteins.

Podocyte Injury Leads to Glomerular Scarring

Except for minimal change disease, diseases of podocytes such as FSGS, membranous nephropathy and diabetic kidney disease are often accompanied by glomerulosclerosis. Several mechanisms lead to this.

Podocytes Produce Increase...