![]()

War as a Factor of Neurological Progress

Tatu L, Bogousslavsky J (eds): War Neurology.

Front Neurol Neurosci. Basel, Karger, 2016, vol 38, pp 22-30 (DOI: 10.1159/000442566)

______________________

Impact of 20th Century Wars on the Development of Neurosurgery

Justin Dowdy · T. Glenn Pait

Department of Neurological Surgery, Jackson T. Stephens Spine and Neurosciences Institute, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Ark., USA

______________________

Abstract

The treatment of neurosurgical casualties suffered during the wars of the 20th century had a significant impact on the formation and early growth of neurosurgery as a specialty. This chapter explores how the evolution of military tactics and weaponry along with the circumstances surrounding the wars themselves profoundly influenced the field. From the crystallization of intracranial projectile wound management and the formal recognition of the specialty itself arising from World War I experiences to the radical progress made in the outcomes of spinal-cord-injured soldiers in World War II or the fact that the neurosurgical training courses commissioned for these wars proved to be the precursors to modern neurosurgical training programs, the impact of the 20th century wars on the development of the field of neurosurgery is considerable.

© 2016 S. Karger AG, Basel

‘I would remind you again how large and various was the experience of the battlefield and how fertile the blood of warriors in rearing good surgeons.’

Hieronymous Brunschwig (1450-1512) [1]

Throughout human history, war and the subsequent need for treatment of war wounds has provided a fecund environment for the development of medicine as a whole. The origin of surgery is particularly rooted in the treatment of injured participants of war and combat. Moreover, innovation in war methods and weaponry has also served to catalyze corresponding advances and evolution in surgical treatment. The 20th century, via a combination of scientific progress and advances in combat methodology, set the stage for the emergence and rapid development of the field of neurosurgery.

Neurosurgery as a specialty remained in its infancy leading up to the turn of the 20th century and was nurtured primarily by two specific occurrences in the preceding century. The pioneering work of 19th century neurologists was instrumental in creating the field of cerebral localization and, consequently, the specialty of neurology by the end of the 1800s [2, 3]. Another deeply important development for the entire field of surgery occurred in the late 19th century with the 1867 publication in Lancet of ‘On the Antiseptic Principle in the Practice of Surgery’ by Joseph Lister (1827-1912), which revolutionized the field of surgery via the introduction of antisepsis in the operating theater [4]. Armed with a rapidly improving knowledge of cerebral localization and antiseptic technique, the forefathers of neurosurgery, Sir William Macewen (1848-1924), Sir Victor Alexander Haden Horsley (1857-1916), William Williams Keen Jr. (1837-1932), Ernst von Bergmann (1836-1907) and ultimately Harvey Cushing (1869-1939), among others, were able to transform the prospect of safe, successful cranial surgery from the province of the plausible to the probable in the years leading up to the Russo-Japanese War and World War I (WWI) [5-7].

Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905: Inouye Maps the Visual Cortex

The Russo-Japanese war fought in the early 20th century provided Japanese Army ophthalmologist Tatsuji Inouye (1881-1976) with the opportunity to study occipital bullet wounds and visual field deficits. Using a stereotactic three-dimensional skull model that he invented, Inouye created the first accurate map of the primary visual cortex. Inouye's work produced important insights into the workings of the human visual system: namely, he discovered that central macular visual input localizes to the occipital pole (with a relatively higher degree of cortical representation compared to peripheral vision) and that the calcarine fissure serves as a cortical partition between the upper and lower visual fields [3].

World War I (1914-1918): Head Injuries and the Rise of Neurosurgery as a Specialty

Despite improving outcomes and a call to action delivered by Harvey Cushing in a 1905 lecture entitled ‘The Special Field of Neurological Surgery’ [8], the field itself was not widely recognized as a distinct specialty within the medical community at the onset of WWI. The evolution of combat weaponry during this time period, however, played a key role in creating the need for large numbers of cranial surgeons during WWI. Immediately prior to the eruption of WWI, significant advances in munitions technology and war methodology in the form of the development and widespread employment of automatic rifles and heavy artillery would provide the conditions from which an overwhelming amount of penetrating cranial trauma would soon emerge [6, 9]. Consequently, significant progress was made in the description and treatment of these penetrating cranial traumas during WWI. Building on the considerable work of Robert Barany (1876-1936), Percy Sargent (1873-1933) and Edmond Velter (1884-1959), among other European neurosurgeons enveloped in the treatment of cranial injuries since the outbreak of WWI [6, 10], Cushing codified the classification and management of penetrating cranial injuries [11] and demonstrated a near halving of the mortality rate in penetrating craniocerebral trauma with techniques attributed to the war experience [6, 10-12]. One of the more insightful recommendations Cushing advocated is the early operation of head-injured patients in more forward-located hospital camps, succinctly stating ‘the farther back a man with a cranial wound goes, the more gloomy becomes the prognosis’ [13]. Cushing explained that ‘the accepted high mortality of the craniocerebral cases could be reduced fully 50% if these cases were operated upon in forward areas. A series of about 200 patients operated upon in the fall of 1917 at a casualty clearing station of the British Expeditionary Force, which was given over entirely to wounds of the head, gave 28.5% mortality; a similar series operated upon at a later period by members of the same team in an American base hospital attached to the British Expeditionary Force gave a mortality of about 45%’[12].

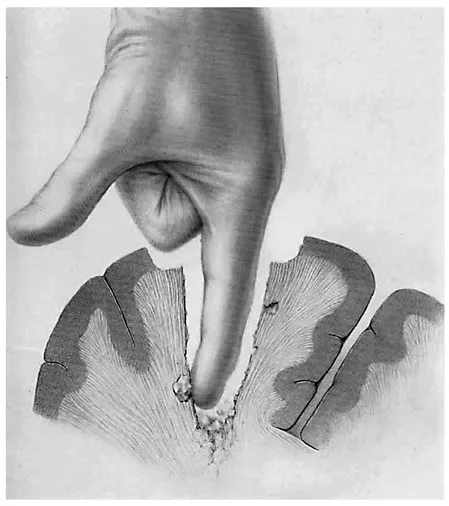

Fig. 1. Illustration depicting digital exploration of a missile tract, which was a common practice used in the earlier wars of the 20th century to remove foreign bodies and bone fragments in penetrating head injuries. Figure reproduced from [17]. (Public Domain.)

Additionally, the great need for capable cranial trauma surgeons in WWI provided the impetus for the development of a rudimentary neurosurgical training curriculum that is the antecedent to modern training programs. Shortly after the U.S. declaration of war on April 6, 1917, preparations were made to begin training surgeons in the treatment of head injuries. This culminated in the creation of a 10-week course given in several American cities, which ultimately graduated 230 surgeons who went on to treat cranial war wounds, three of whom continued to practice neurosurgery after the war. Although necessarily limited in scope and length, this training program served as the first widespread attempt at systematic neurosurgical training [14].

The sheer number of casualties with penetrating head injuries and their exposure to countless medical personnel throughout the war would ultimately compel the medical establishment into recognizing this fledgling specialty shortly after the war's end. Soon after the Treaty of Versailles was signed, at the annual meeting of the American College of Surgeons, then-President William Mayo (1861-1939) declared the founding of neurological surgery as a distinct surgical specialty [14]. Thus, WWI, as a consequence of innovations in combat methodology and in combination with the pre-war momentum surrounding neurosurgery, paved the way for its rise as a surgical specialty.

World War II (1939-1945): Progress in Spinal Cord Injury Treatment and Cranioplasty

Whereas WWI set the stage for the final maturation of neurosurgery into a distinct specialty and saw significant inroads made in the management of penetrating cranial trauma, World War II (WWII) would prove to be a watershed moment in the history of the treatment and outcomes of spinal cord injuries (SCIs). Cushing, in his summary of the neurosurgical activities of WWI, wrote that SCIs ‘did very badly throughout’, with an 80% mortality rate in the first few weeks alone, largely attributable to infections from sacral decubitus ulcers and bladder catheterization [12]. Due to the adoption of a multidisciplinary approach to spinal-cord-injured patients incorporating improved bladder management, bedsore prevention and neurorehabilitation, great strides in SCI treatment were realized [15-17]. Howard Rusk (1901-1989), the founding father of rehabilitative medicine, wrote ‘It is worth noting that of the four hundred men who became paraplegics in World War I, a third died in France, another third died within six weeks thereafter, and of the remaining third, 90% were dead within a year. In World War II there were 2,500 American service-connected combat paraplegics, and three fourths of them were alive twenty years later. I might add parenthetically that, of these survivors, 1,400 were holding down jobs’ [17]. Barnes Woodhall (1905-1985) and R. Glen Spurling (1894-1968), two well-renowned WWII neurosurgeons, would later summarize, ‘there is no brighter chapter in the history of neurosurgery in WWII than the competent and compassionate long-term management of injuries of the spinal cord’ [18] and that ‘more was achieved for the paraplegic in WWII, in comparison with his status in previous wars, than for any other type of casualty’ [19].

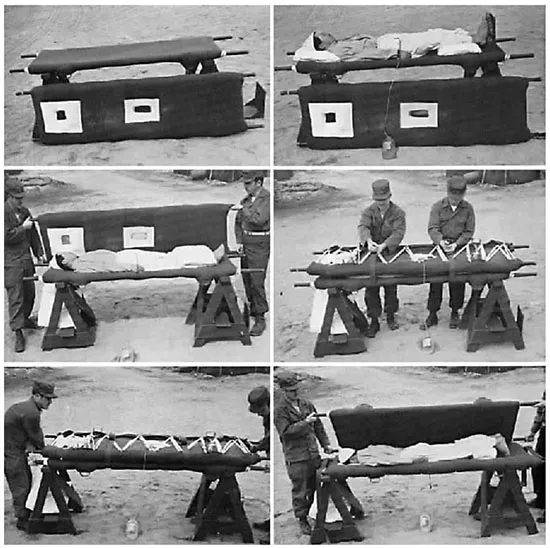

Fig. 2. Photo illustrating the litter-turning method. Widely implemented in WWII, the litter-turning method was instrumental in preventing the formation of sacral decubitus ulcers in spinal-cord-injured soldiers and was one of the many innovations during WWII that contributed to a significant decrease in the mortality of these patients both during WWII and subsequently in t...