eBook - ePub

Over the Lip of the World

Among the Storytellers of Madagascar

Colleen J. McElroy

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 250 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Over the Lip of the World

Among the Storytellers of Madagascar

Colleen J. McElroy

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Gifted travel writer, poet, professor of English, and insightful observer of human nature, Colleen McElroy journeyed to Madagascar to undertake a Fulbright research project exploring Malagasy oral traditions and myths. In Over the Lip of the World she depicts with equal verve the various storytelling traditions of the island and her own adventures in trying to find and record them. McElroy's tale of an African American woman's travels among the people of Madagascar is told with wit, insight, and humor. Throughout it she interweaves English translations of Malagasy stories of heroism and morality, royalty and commoners, love and revenge, and the magic of tricksters and shapechangers.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Over the Lip of the World est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Over the Lip of the World par Colleen J. McElroy en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Literature et Literary Criticism. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

LiteratureSous-sujet

Literary Criticism

CHAPTER VI

PEOPLE OF THE HIGHLANDS; PEOPLE OF THE LONG VALLEYS; PEOPLE OF THE THORNS

Lamba tohy tsy an’ olon-jejo, lamba lava tsy an’ olon-kamo.

The well-wrapped lamba does not belong to the wanton, nor does the long lamba to the lazy.

The well-wrapped lamba does not belong to the wanton, nor does the long lamba to the lazy.

On Sunday afternoons, in meeting places on the outskirts of Tana, people come from all over the country to listen to hiragasy, the song-poems of Madagascar. They meet in churches, school auditoriums, dance halls, and cattle auction rooms. They come from districts throughout the capital city, and from surrounding villages—old and young, male and female, city and village folks.

I was recovering from a fever the first time I attended a Sunday hiragasy. I had worried that I would succumb to the medication I was taking, but once I was inside, sitting on one of the hard benches in a school auditorium, the lingering traces of my illness vanished as I watched the performance of singers and musicians wearing the colors of their districts—their coats and dresses piped in contrasting colors—red for the soil of Madagascar and sunsets that ignite the sky, and blue for the endless sky and for the ocean that surrounds the land of the ancestors. I was caught up in another fever, applauding with the crowd to songs of love and death, wealth and pride, war and poverty, families and enemies, wisdom and foolishness, all echoing in the rafters with the drumbeat and trumpet blasts of the musicians.

Hira, to sing. Gasy, of the Malagasy people. I could find no definition for hiragasy in the few Malagasy—English dictionaries that were available. In those dictionaries, hira was defined simply as singing, but there was no reference to the special songs of hiragasy. I surmised that the songs of the people must have been too dangerously close to notions of sedition for the colonialists and missionaries who first constructed those dictionaries. Perhaps they were right to be worried. There was certainly the beauty of independence in the songs, a sense that the singers had tapped into a great treasury of Malagasy spirit and determination through hainteny (poems), ohabolana (proverbs), and angano (stories). The song-poems were woven into a tapestry of oral traditions—traditions that had lived on despite attempts during colonial rule to suppress them.

Song-poems of hiragasy were steeped in the history and culture of the Malagasy people, but the costumes reflected colonial intrusion, albeit tempered with Malagasy flair. They worked in teams, each group consisting of ten or twelve singers, more or less evenly divided between men and women; and there were three or four musicians playing percussion, reed, and stringed instruments. The men wore fedoras and frock coats, their lambas draped in the manner of bandoliers. Watching the men, I could easily recall the New Orleans Preservation Blues Bands I’d seen marching in Mardi Gras parades, or thirty-second degree Masons in their black suits and white bandoliers on parade in New York, St. Louis, or Atlanta. In one hiragasy group, a young boy danced on one leg for what seemed like twenty minutes. He crossed and recrossed the leg he kept off the ground, his gestures acknowledging the presence of the ancestors, the vitana or destiny of the people. It was a dance that could only be performed by someone who was youthful, who was able to make difficult movements seem easy. In another group, the orator, whose duty it was to call forth the songs, was over six feet tall, a long-limbed man with pronounced cheekbones and a determined jaw. (I would not see another Malagasy that tall until I met the poet M. Rado.) The orator had a commanding presence, his words resounding throughout the auditorium when he began the performance by placing his gray fedora on the drum to show respect for the ancestors before he called upon their guidance.

Traditionally, hiragasy was used to entertain kings and visiting royalty, but the song-poems also were steeped in village history, and carried into the twentieth century by the Malagasy insistence on paying homage to the ancestors. At the beginning of each performance, the ancestors were called upon. “Please help us,” the orator beseeched. “We are poor and not wise as you. We are still here among the living.” While he spoke, everyone took their positions—men, women, men, women—as if they were at a cotillion. The women singers wore floor length dresses, more early nineteenth century than twentieth: short puff sleeves, high necks, abbreviated lambas worn as scarves. Their voices held the high, lilting quality of choral singers.

Throughout the country, I repeatedly saw the link between music and the oral tradition. Wherever Tiana and I visited storytellers, we also found musicians. In Toliara, we had watched a performance of M. Manindry’s dance troupe before listening to the storyteller, M. Soaraza. In Fianarantsoa, we listened to street musicians play the wonderful melodies of the jejy voatavo before returning to Mme. Alphonsisme’s house to listen to her stories under the blanket of a starry sky. Sometimes a visit yielded only music. Such was the case in Ambondrona and Ambalatoratasy, two small villages near Fianarantsoa.

Simon had taken us into the hills to find a storyteller, but instead we found several villages recovering from the effects of malaria. These were tiny farming communities nestled in hillsides where there were more rocks than trees, and unmarked roads were, often as not, impassable. In Ambalatoratasy, where several people had been taken ill from the disease, I met Efraim Romaine, who was about nine years old and the youngest storyteller I encountered. He had been out of bed for only a few days after battling malaria, and remembering how a month earlier I’d battled an infection, I suggested he needed to rest. But he shyly tried to piece together a tale he’d been told by his grandmother. Although his efforts yielded only fragments of the story, I still saw clear promise of his beginnings as an orator. The older boys of the village fared only a little better with their handmade guitars and drums, but everyone joined in, including Efraim’s family, all of them dancing and applauding the young musicians.

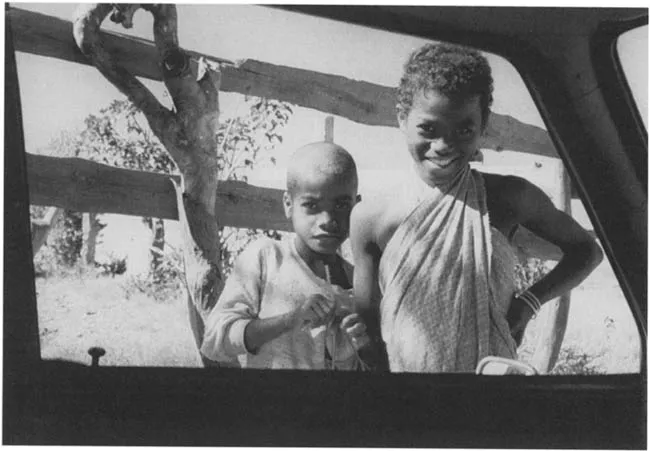

Chatting with village boys framed in a car window, Ambalatoratasy

Later, we continued up the gravel road toward Ambondrona. In a village nearby, we learned that the community was preparing for a funeral. Malaria had taken its toll in the area with eight people dead, including three children. I waited in the car while Tiana went with Simon and Haingo to learn where the funeral would be held. While I waited, two young boys, curious about a private car so near their homes, chatted with me through the window, our language consisting most...