![]()

1

Icebreaker

Nói the Albino (2003) may be only one of a handful of Icelandic films to have traveled the world over, garnering the praise of critics and selling plenty of tickets along the way, but as a production, it was conceived with modest expectations—even on an Icelandic scale. In fact, first-time feature director Dagur Kári and his producers at Zik Zak Filmworks, Þórir Sigurjónsson and Skúli Fr. Malmquist, saw Nói the Albino as a mere stepping-stone, as a film that would attract a little bit of attention and thus pave the way for a larger project—The Good Heart. But as it turned out, they pretty much began at the top.

In retrospect, Nói the Albino's significance extends well beyond its merits as a film inasmuch as it played a crucial role in the emergence of Zik Zak as a key Icelandic production company. Zik Zak was arguably the first of its kind in Iceland, as owners Sigurjónsson and Malmquist specialized in financing and production and showed no desire to direct the films they produced. However, Nói the Albino was neither Dagur Kári's first film nor the first film produced by Zik Zak. Sigurjónsson's and Malmquist's first production was Ragnar Bragason's debut film Fiasco (Fíaskó, 2000). Offering a comic cross section of Icelandic society, this film displays a competence and self-assurance that in every way belies its makers' lack of experience. However, it was overshadowed at the local box office by maverick filmmaker Friðrik Þór Friðriksson's very successful Angels of the Universe (Englar alheimsins, 2000) and Baltasar Kormákur's debut and international hit 101 Reykjavík (2000).1 Although 101 Reykjavík was Kormákur's first film, it was produced by the director's own company, as was customary in Icelandic cinema. Similarly, Angels of the Universe was produced by Friðriksson's Icelandic Film Corporation, the long-standing powerhouse of the national film industry. It was as good a sign as any of the changes taking place within the industry when Friðriksson, with his company bankrupt, agreed to direct the Zik Zak project Niceland (Næsland, 2004). Based on a screenplay by writer Huldar Breiðfjörð, this film was developed in-house. It is worth noting that Breiðfjörð had also scripted Zik Zak's second movie, the omnibus film Dramarama (Villiljós, 2001), which includes an installment by Bragason as well as by Dagur Kári.

Composed of five thematically related parts connected by the loosest of narrative threads, Dramarama opens with Dagur Kári's “Corpse in the Crate” (Líkið í lestinni). It focuses on a professional hearse driver, Ívar (Björn Jörundur Friðbjörnsson), who is accompanied by his parrot (whose voice is provided by legendary Icelandic singer Megas) and who discusses his marital problems and the experience of driving a fifteen-year-old to his funeral earlier in the day. Dagur Kári did not write “Corpse in the Crate,” unlike his other work, but it does have a thing or two in common with his other films, thematically, through its emphasis on loneliness and isolation, with a touch of the absurd in the form of the talking parrot, and stylistically, through its use of expressive colors. The dominating blue color, motivated by the nighttime setting of Dagur Kári's contribution, is intercut with brief shots in a striking yellow color of the fifteen-year-old about to commit suicide. Dramarama is also suggestive of Zik Zak's willingness to grant its directors stylistic freedom, as all five parts vary considerably in terms of style, somewhat accounting for Dramarama's unevenness. Regardless, its narrative comes full circle, as the lights go out in Reykjavík and the hearse driver crashes into a moving car carrying the central characters of the concluding part. What we see here is a combination of death and darkness that will recur in a different and more elaborate form in Nói the Albino.

Prior to his work on Dramarama, Dagur Kári directed two award-winning short films that, in addition to being fascinating works in their own right, can be seen in retrospect to contain the seeds of his feature work. Apart from its opening credits scene, which offers a panorama of central Reykjavík, Old Spice (1998) is confined to the interior of a barbershop where the elderly barber Einar (Rúrik Haraldsson) receives a new customer, another elderly man, Kaj Pedersen (Karl Guðmundsson). When he receives no service despite being the only customer, Kaj gets ready to leave; Einar, puzzlingly, is seen sipping out of an Old Spice aftershave bottle throughout. It is then that Einar explains to him that the bottle is filled with cognac and that he is expecting an old customer named Ármann who continues to show up for his monthly haircut despite having passed away while driving to his last appointment. Einar's story is confirmed when the barbershop begins shaking back and forth, and the two call in a medium to intervene in the situation. The medium Jónatan (Eggert Þorleifsson) explains to them that Ármann has lingered in this world due to confusion resulting from an all-too-sudden death. Jónatan also mentions that Ármann inexplicably kept rambling about a pinball machine. Einar now discloses that the distinguished gentleman and stout alcohol reformer Ármann visited the barbershop not only for his monthly haircut but also for the chance to get drunk and play pinball with Einar after hours, safely hidden from view in the back of the shop. Kaj does not get his haircut, as it is after closing time when Jónatan leaves, but he follows in Ármann's footsteps and plays some pinball while having a drink with Einar in the back.

Unlike Old Spice, which is an Icelandic production shot in Icelandic, Lost Weekend (1999) is a Danish production in Danish. At thirty-five minutes, approximately twice as long as Old Spice, it is the story of the DJ Emil (Thomas Levin), who after a wild night at his club awakens with a perfect stranger in an unknown hotel room. Save for the film's opening at the club, and some recurring flashbacks to that setting, Lost Weekend is confined to the bleak-looking hotel, as Emil cannot bring himself to leave and face the “real” world again. The two locations also contrast stylistically, with the fast-paced club scenes making way for the much more leisurely paced hotel scenes. In this sense, there are clear parallels with Old Spice, which similarly emphasizes spatial confinement in the barbershop scenes. The stranger turns out to be Ida (Rikke Louise Andersson), who not only works at the hotel but is also the daughter of its owner, Hjalte (Anders T⊘fting Hove), a rather grim-looking eccentric obsessed with the hotel's minibars. Having gone on a drinking binge with Ida, with whom he empties most of the minibars, Emil decides to face up to the real world again. He thus sells his record collection to pay his bill and declines Hjalte's offer of employment. However, no sooner has Emil left the building than he leaves this world altogether, hit by an oncoming vehicle.

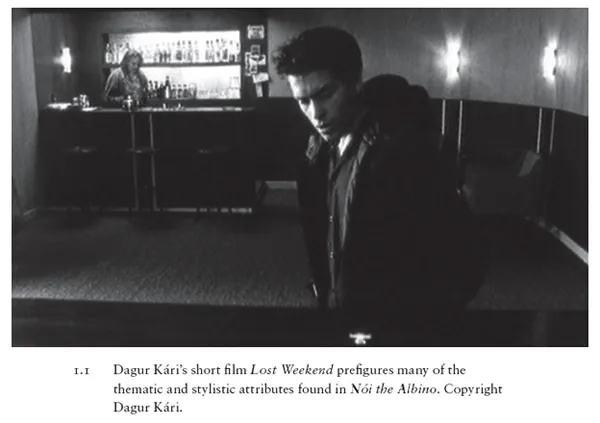

The two shorts have numerous things in common with Nói the Albino. As director Dagur Kári himself points out, they are both confined to explicitly demarcated locations in a manner typical of sitcoms. Stylistically, they are not only for the most part leisurely paced but also characterized by distinct color palettes. Although this use of color is less pronounced in Old Spice, the film does have a golden brownish hue not unlike the color of the precious cognac in the aftershave bottle of the title. As such, the film evokes a past era (although the actual time setting is left ambiguous). Lost Weekend, in contrast, has a more distinctive palette, its arresting blue green hue adding to the hotel's outlandishness and further emphasizing its more overt stylistic playfulness (fig. 1.1). Perhaps no less than their color palettes and leisurely pace, both shorts are characterized by a similar fondness for and devotion to certain unusual objects, often tied to a bygone era. The hotel and the barbershop locations are clearly key in this regard, but so are the records, the record player, and the minibar bottles in Lost Weekend and the Old Spice bottle and the pinball machine in Old Spice. What is more, these material reminders of an earlier era all serve a function that recalls that of the Mastermind game, the Magic Cube (later known as the Rubik's Cube), the pancake pan, and, most obviously, the red View-Master in Nói the Albino.

The two short films also revolve thematically and narratively around death, and although the medium Jónatan, a handyman, in Old Spice evokes the fireman Gylfi in Nói the Albino, it is the unexpected death of Emil, with its apparently minimal narrative preparation, that especially recalls the handling of death in Nói the Albino. Emil's death is also accompanied by a melancholic song, although it is performed by Radiohead rather than Dmitry Shostakovich, and like Nói, Emil has suffered from loneliness and isolation. He has been rejected by his newfound love Ida (the two do discuss travel plans, although they end up camping in the hotel room owing to Emil's fear of the outside world), and he seems out of touch with the world at large. The crucial difference is that in Nói the Albino, death claims the lives of all but the central protagonist.

Following their work together on Dramarama, Zik Zak and Dagur Kári joined hands again to produce the director's first feature film. Their teamwork was in many ways based on a perfect fit, although one can only speculate about the extent to which Nói the Albino's success results from its particular production circumstances. Here was a young director making his debut, without any industry credentials, partnering with a newly established production company that not only supported director autonomy but was granting it to directors making their first features. Even though their first three films met with little box-office success, producers Sigurjónsson and Malmquist were not discouraged from bringing Nói the Albino to the silver screen. This is somewhat striking inasmuch as the film, despite its modest budget of 1.1 million euros (1.4 million dollars), was far from easy to finance. It was allocated a production grant of 25 million Icelandic kronur (approximately a quarter of its budget) by the Icelandic Film Fund but received no support from either Eurimages or the Nordic Television and Film Fund, institutions that have been instrumental in funding Icelandic films with an international pedigree. The lack of support from the latter fund is particularly surprising considering the film's Nordic credentials. After all, not only did Dagur Kári study his craft at the National Film School of Denmark, in Copenhagen, but his crew included fellow students who had worked with him previously on Lost Weekend. The participation of Danish cinematographer Rasmus Videbæk and Swedish editor Daniel Dencik made it a clear instance of Nordic collaboration. Certainly, the film's credited co-producers and financial supporters suggest precisely the form of transnational co-production that is typically favored by Eurimages and the Nordic Television and Film Fund. (The film was co-produced by M&M Productions, Denmark; Essential Filmproduktion, Germany; and The Bureau, England. It garnered financial support from institutions in the three relevant countries in addition to the grant from the Icelandic Film Fund.)

Thus, despite being a low-budget film, Nói the Albino's financing and production preparation was quite complicated, inasmuch as it drew on resources from four different countries. Furthermore, some of the funding had early-shooting stipulations, making for a brief preproduction stage that itself resulted in (among other things) much of the casting being done “on the fly,” as Dagur Kári himself has put it. Rather than being a drawback, however, this aspect of the production process seems to have contributed to the film's lively nature and, arguably, to its almost magnetic qualities. Perhaps something similar could be said about the economical choice of shooting with 16mm film. This particular production decision gives Nói the Albino a far more down-to-earth feel than would have been the case with 35mm. The film's low budget would seem to match the story at the heart of Nói the Albino, which is one of those cinematic texts that tell more by showing less. After all, the story is set in a small village in the far northwest of Iceland, where apparently precious little happens.

* * *

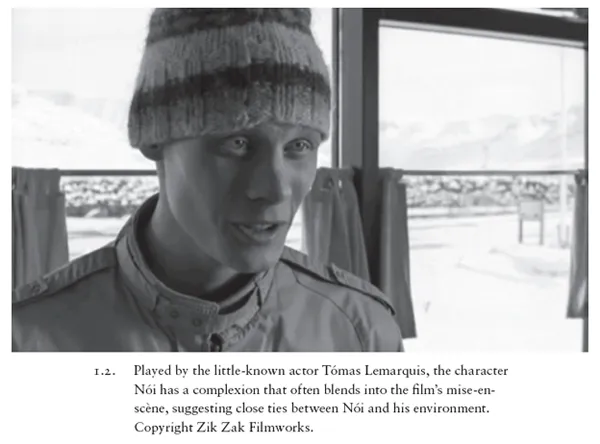

Nói (Tómas Lemarquis) is an only child, approximately seventeen years of age, who lives with his grandmother Lína (Anna Friðriksdóttir) in a small, unnamed village located in the Icelandic Westfjords. The film takes place during winter, and the whiteness of the snow-covered mise-en-scène is mirrored by Nói's complexion. It is this complexion that explains Nói's unusual nickname: Albínói, or Albino (fig. 1.2). Nói's father, Kristmundur (Þröstur Leó Gunnarsson), who goes by the common nickname Kiddi, lives elsewhere in the village and is something else altogether. Indeed, his comparatively dark complexion is embellished by almost pitch-black hair (fig. 1.3). One can only speculate as to whether Nói has inherited his distinctive looks from his mother, for she is nowhere to be seen and plays absolutely no role in the film, just as she would seem to have played no role in his life, save for bringing him into the world.

The daily routines of Nói's life are introduced in the film's early scenes. He is awakened by Lína, who, in a much celebrated shot, fires a shotgun out a window, and the two subsequently have breakfast. Kiddi arrives in his taxicab to drive his son to the local high school. Nói arrives late for a math exam that he is quick to turn in, with nothing but his name filled in, much to his teacher Alfreð's (Guðmundur Ólafsson) evident frustration. He thus quickly escapes the school and heads to the gas station, where he cheats a slot machine out of some coins before purchasing a bottle of his favorite drink, malt. Next door is the home of his much older buddy Óskar (Hjalti Rögnvaldsson), which doubles as the town's used-book store and video-rental store, where Nói finds Óskar reading cynically from S⊘ren Kierkegaard's Either/Or. Nói returns home and climbs down to his basement den, where, agitated, he finds little to do save rub his hands together.

Nói's home, Kiddi's cab, the high school, the gas station, and the book store will all become central sites during the narrative, but even at this first introduction, it is clear from the actions and dialogue of both Nói and the other characters that these sites provide the context for regular and mundane routines. This feeling is accentuated when the camera returns to an overview framing of the village, an image that, here as elsewhere in the film, functions as something of a chapter division. This image is then followed by a couple of shots from within the village, all depicting much snow and no people. In the fourth shot, Nói finally emerges, all by himself and in the distance.2 These shots are suggestive of the lonely and repetitive nature of Nói's life, but things are about to change. Having collected the coins from the slot machine, much as in the first gas station scene, Nói is ready to order his bottle of malt when he suddenly finds himself face to face with Íris (Elín Hansdóttir) (fig. 1.4). Íris, who is the same age as Nói, has just moved to the village from the city. Their first encounter is a little awkward, but the seeds of change have been planted—life will never be the same again. In the book store next door, flipping through some pornographic magazines, which he won from Óskar in one of their regular games of Mastermind, Nói ventures to ask whether Óskar has seen the new girl working at the gas station. Nói, tellingly, flips through the magazines as he asks the question. Óskar promptly warns Nói to stay away from Íris; it turns out that Íris is his daughter.

In what follows, the narrative takes two different if intertwined directions, a positive and a negative one. The former focuses on the development of Nói's romantic relationship with Íris and the other on his increasing difficulties in coping with life in the village. Awakened from his sleep in French class, Nói is summoned to a meeting with a psychologist (Haraldur Jónsson), whom he antagonizes at every opportunity. He visits his father, who, drunk on vodka, reveals that Nói's conception was accidental. He tries, unsuccessfully, to bond with classmate Davíð (Greipur Gíslason), and he makes his teacher Alfreð finally blow his top. Indeed, Alfreð ends up informing headmaster Þórarinn (Þorsteinn Gunnarsson) that either he or Nói must quit the school. With regard to Íris, the situation is rather different. The two are next seen getting along well at the gas station, where Nói teaches her to smoke cigarettes after having purchased his bottle of malt...