![]()

1

The Ottoman Empire at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century

SHORTLY before his death in 1774, Sultan Mustafa III (r. 1757–74) composed a quatrain describing the state of the Ottoman Empire:

The world is turning upside down, with no hope for better during our reign,

Wicked fate has delivered the state into the hands of despicable men,

Our bureaucrats are villains who prowl through the streets of Istanbul,

We can do nothing but beg God for mercy.1

Whether or not fate was responsible for the desperate situation of the empire, both Mustafa III and his brother Abdülhamid I (r. 1774–89) spared no effort in the attempt to reform it. But it was Mustafa III’s son Selim III (r. 1789–1807) who would make the most significant effort yet to reverse the seemingly inexorable process of decline. It was not that the empire had regressed in its administration, economy, or culture, as is often assumed; on the contrary, many of its provinces were thriving in all these respects. But from the perspective of its rulers, the decreasing ability of the empire to compete militarily and economically with its continental rivals was cause for considerable alarm.

A TOUR OF THE OTTOMAN LANDS AT THE TURN OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

The most salient characteristic of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the eighteenth century was its decentralization. In fact, the Ottoman state can only be considered an empire in the loose sense in which the term is used to refer to such medieval states as the Chinese under the late T’ang dynasty. Its administrative establishment, economic system, and social organization all call to mind the structure of a premodern state. On paper, Ottoman territory at the turn of the nineteenth century stretched from Algeria to Yemen, Bosnia to the Caucasus, and Eritrea to Basra, encompassing a vast area inhabited by some 30 million people.2 In practice, the reach of the Ottoman government in Istanbul rarely extended beyond the central provinces of Anatolia and Rumelia, and then only weakly.

The remainder of the “sultanic domains” displayed a rich variety of administrative patterns, the common theme of which was the dominance of quasi-independent local rulers. Strong governors who controlled vast swathes of territory with the help of private armies naturally had their own styles of administration. Institutions that looked the same on paper worked quite differently in practice; the formal bureaucratic structure in Egypt under Mehmed Ali, for instance, might seem nearly identical with that of Ali Pasha of Tepelenë. In reality, however, Mehmed Ali’s relentless efforts to transform the Egyptian bureaucracy in the early years of the nineteenth century turned it into a modern, effective machine of government, whereas Ali Pasha of Tepelenë’s despotic administration was rigid and inefficient by comparison.3 In the periphery, particularly in Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, fluid boundaries fluctuated in tandem with the vicissitudes of tribal loyalty. Everywhere, population data, even vital information on taxpaying households, was hopelessly out of date. The first comprehensive modern Ottoman census did not take place until 1831.

In Europe, the empire faced imperial competitors who were steadily eroding the Ottoman gains of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Of these, Russia and Austria posed perhaps the most formidable threats to the integrity of the empire. By the terms of the Küçük Kaynarca Treaty of 1774, the Crimean Khanate—the only de jure autonomous Muslim administrative unit in the empire—became an ostensibly independent state, only to be swallowed by Russia nine years later. The two other autonomous Ottoman principalities, Wallachia and Moldavia, came under Russian protection. Thereafter, they drift ed steadily away from Ottoman control. Local hospodars had ruled Wallachia and Moldavia on behalf of the Ottoman sultan until 1715–16, when the Ottoman center began to award these positions to imperial dragomans belonging to the major Greek Phanariot families in Istanbul.4 This practice provoked considerable discontent in the principalities. Local resentment grew when the Ottoman administration introduced new trade regulations that required the sale of grain and animals to the imperial government at a set price. Russia, by contrast, came to be seen as the beneficent Orthodox protector. This sentiment acquired a legal basis in Article 16 of the Küçük Kaynarca Treaty. Thus emboldened by Russian support, notables and intellectuals demanded that the Ottomans grant further autonomy to the principalities. In 1790, Ioan Cantacuzino submitted a petition to the Ottoman government in which, inter alia, he asked that they be granted the right to elect rulers according to local traditions. The Ottomans responded to such requests with a number of formal concessions, embodied in the New Law of 1792, which regulated relations between the imperial center and the principalities.5 In practice, however, the Ottomans conceded little, and consequently failed to win the support of local notables.

The tributary city-republic and major port of Ragusa (Dubrovnik)—an Ottoman Hong Kong on the Adriatic, linking the imperial heartlands with Europe—was the center of endless Ottoman, Habsburg, and Venetian diplomatic maneuvers and bargains. Although Vienna became the second protector of Ragusa in 1684, the Ottomans succeeded in reestablishing sole protection in 1707 and kept this city-republic in the Ottoman fold until the French occupation in 1806. The French integrated Ragusa into their Provinces illyriennes in 1808, but ceded it to Austria at the Congress of Vienna, whereby the Ottomans lost this vital trade link forever.6

The remaining Ottoman provinces were divided into two major groups. The provinces in which the distribution of land was effected according to the timar system formed the first group. In these territories, Ottoman viziers, princesses, governors, and subgovernors administered royal fiefs (timars), collecting revenues through tax farmers. In principle, these provinces operated as autonomous financial units charged with maintaining a balanced budget. Examples of this type of province are Anatolia, Rumelia, Bosnia, Erzurum, and Damascus.

The second major group of provinces comprised those in which the timar system was not applied. Here the state claimed all tax revenues, paying governors a yearly salary in cash (the salyâne), while local authorities were responsible for the collection of taxes and the payment of all local salaries. The best examples of such provinces are the North African domains, Basra, Egypt, several Mediterranean islands, and parts of Baghdad province. Of these, Baghdad, Basra, and Egypt transferred surpluses to the central government on a yearly basis, whereas other provinces of this type merely submitted gifts.

The Arab provinces had another distinctive administrative-economic characteristic. Following the conquest in the sixteenth century, the Ottoman authorities had decided not to alter the preconquest systems of land tenure and taxation, in order to ease the incorporation of these provinces into the empire. Accordingly, the inhabitants continued to pay taxes in the particular manner to which they had been accustomed for centuries. For instance, in Sayda (modern-day Syria and Lebanon with the exclusion of Aleppo province), the inhabitants paid a cash tax on saplings to the imperial treasury and another in kind on wheat and barley to local state depots. In Mosul, farmers paid half of their harvest as a tithe (öşür), while tribesmen paid taxes based on the number of tents or herds they owned. In Cyrenaica, the determining factor was the number of wells in a given tribe’s territory.7

Among the Arab provinces, the North African dominions of Algeria, Tunis, and Tripoli of Barbary enjoyed varying degrees of self-rule. These provinces had been incorporated into the empire in the sixteenth century by leading corsairs, such as Hayreddin Barbarossa, who pledged allegiance to the sultans and served in the Ottoman navy. Tunis and Algeria were subsequently ruled by Ottoman governors in consultation with councils led by Janissary commanders of the local army. The leaders, or Dayıs, of these councils gradually encroached on the authority of the governors. They even seized power in Tunis and Algeria in 1582 and 1670, respectively. Although a later governor, Ramaḍān Bey, managed to reestablish central control in Tunis, one of his followers, Ḥusayn Bey, founded a hereditary governorship in 1705. Thereafter, Tunis became a virtually independent state with only loose ties to the imperial center. However, even after the establishment of French colonial rule in Algeria in 1830 and the declaration of the French protectorate in Tunisia in 1883, the Ottoman administration continued to claim a border with Morocco, considered Tunisia an autonomous province, and classified Algeria as an imperial region (the Ottoman term hıtta refers to a territory with vague boundaries).8

In 1711, a Janissary officer by the name of Karamanlı Ahmed became governor of Tripoli of Barbary and Cyrenaica (forming the Ottoman province of Tripoli). He subsequently established a hereditary governorship that lasted more than a century. Thereafter, Tripoli too became an essentially independent province. Ahmed Bey and his successors went so far as to assume the title “commander of the faithful,” a label hitherto restricted to the Ottoman Sultan as Caliph. The local economy thrived on piracy in the Eastern Mediterranean. But state-sponsored piracy and the regular holding of hostages for ransom inevitably led to trouble with foreign governments. In 1798, for instance, the governor demanded 100,000 French francs from the Swedish government, in addition to a yearly payment of 8,000 French francs, in return for safe passage for Swedish vessels. The Swedes’ refusal prompted an all-out attack on their shipping, and only Napoleon’s personal intervention secured the release of hundreds of hostages at a reduced rate of 80,000 French francs on top of the annual fee.9 In 1801, a spate of attacks provoked the U.S. government to launch its first naval expedition to the Mediterranean. This conflict, known as the Tripolitan War, ended with a peace treaty signed on June 4, 1805. American terms were harsh and dealt a shattering blow to a state that was heavily dependent on ransom revenue. The Anglo-Dutch expedition of 1816 against Algiers and the resultant pressure applied by the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle (1818) worsened the economic situation and paved the way for the reestablishment of Ottoman central control in 1835.

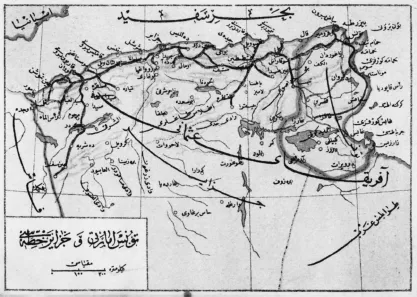

FIGURE 2. A map showing “Ottoman Africa” including the “Principality (Emaret) of Tunis” and the “Region (Hıtta) of Algeria,” from the Memâlik-i Osmaniye Ceb Atlası: Devlet-i Aliyye-i Osmaniye’nin Ahvâl-i Coğrafiye ve İstatistikiyesi, eds. Tüccarzâde İbrahim Hilmi and Binbaşı Subhi (Istanbul: Kütübhane-i İslâm ve Askerî, 1323 [1905]), p. 64 (map section).

In the province of Egypt, conquered by the Ottomans in 1517, local Mamluk houses held almost all the bureaucratic positions by the end of the eighteenth century. The leader of the strongest of these houses would be elected Shaykh al-Balad (Chief of the City). He ruled the country from Cairo in spite of the continued presence of an Ottoman governor.10 Over the course of the eighteenth century, Ottoman frustration at this indignity gave way to a policy of restraint and accommodation11—an approach bolstered, no doubt, by the substantial tax revenues remitted from the province by local amīrs, who increasingly took over the duties of tax collection from the imperial authorities.12 Bonaparte’s invasion in 1798 reinforced the separatist drift of Egypt, completing the foundations for virtual independence under a hereditary dynasty.

The province of Ethiopia included parts of modern-day Eritrea and the Sudan, and was established in 1555 to preempt Portuguese domination of the region. But by 1800, it had lost so much territory to the Ethiopi...