![]()

PART I

Roots: Memories of Home

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Ethiopia: The Lie of the Land

Modern, landlocked Ethiopia occupies the largest portion of the territory known as the Horn of Africa. Bordered on the south by Kenya and on the west by Sudan and South Sudan, Ethiopia’s access to the Red Sea in the north is blocked by Eritrea and in the northeast by Djibouti. The eastern tip of Ethiopia is wrapped by large, number-7-shaped Somalia, whose long coastline takes in both the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. The topography of Ethiopia is complex, but the center of the country is dominated by a high plateau with an altitude ranging from 1,290 meters to a peak of more than 4,500 meters. The central plateau is intersected diagonally by the Great Rift Valley. From this plateau, the land drops away—in places sharply—to the lowlands of the north, west, south, and east. Lake Assal, in the Afar or Danakil Depression, one of the hottest and driest places on earth, constitutes Ethiopia’s lowest point at 155 meters below sea level. The country is watered by the many rivers that rise in the mountainous regions of the plateau and wash down toward the Nile on the west, with others, like the Awash, flowing into Djibouti and Somalia; and the Omo, feeding into Lake Turkana.

Drawing an arc from the western border of Ethiopia with Sudan to the Kenyan border in the southwest is Oromia, the region occupied by the Oromo people (see map 1.1). Oromia, constituting one of nine ethnically defined administrative regions (or kililoch), occupies the largest land allocation of all the regions (353,007 square kilometers), which accommodates the largest single population group (approximately 40 percent of a total estimated Ethiopian population in 2016 of 102,374,044).1

The topography of the Oromia region is varied and is generally divided into three principal topographical categories, ranging from the mountainous areas of the Ethiopian central plateau in the north to the grassy lowlands in the east, west, and south. Despite several substantial rivers and other water sources in Oromia, the region, like the rest of Ethiopia, is vulnerable to periodic and often devastating climate-driven droughts and famine.

MAP 1.1. Modern Ethiopian administrative regions (source: adapted by Sandra Rowoldt Shell).

More specifically, the three major topographical localities of the Oromia region can be divided into (a) the western highlands and lowlands; (b) the eastern highlands and lowlands; and (c) the areas falling within the East African Rift Valley region.

In the context of the Oromo slave children, the most significant of these localities are the western highlands and lowlands. Under the present political dispensation, this area of Oromia takes in the modern administrative zones of North Shewa, West Shewa, Jimma, Illubabor, East Wellega, and West Wellega. In general, the region features a rugged plateau with a slightly lower altitude than the land farther north. The highest peak is Mount Badda, rising to 3,350 meters above sea level. The western lowlands cover a smaller area of this region.

The eastern highlands and lowlands, incorporating the Arsi, Bale, Borena, East, and West Hararge zones, have an altitude ranging from 500 meters above sea level in the undulating lowlands to Batu Mountain, which peaks at 4,307 meters above sea level. The plateau here features inhospitable rocky desert land supporting a sparse population.

Some forty million years ago, one of Africa’s most spectacular geological phenomena resulted in the splitting of the African tectonic plate, forming a continuous rift stretching 6,000 kilometers from northern Syria to Mozambique. The entire geological phenomenon, still often described loosely as the Great Rift Valley, is actually a series of separate rifts. Where the valley intersects Ethiopia from the Red Sea in the north through to the Kenyan border in the south, it is more accurately described as the Great East African Rift. Splitting Oromia from north to south, the East African Rift Valley region takes in part of the Arsi and East Shewa zones. Volcanic hills, lakes, and depressions fill the valley, while high mountains frame the ridge of the rift.

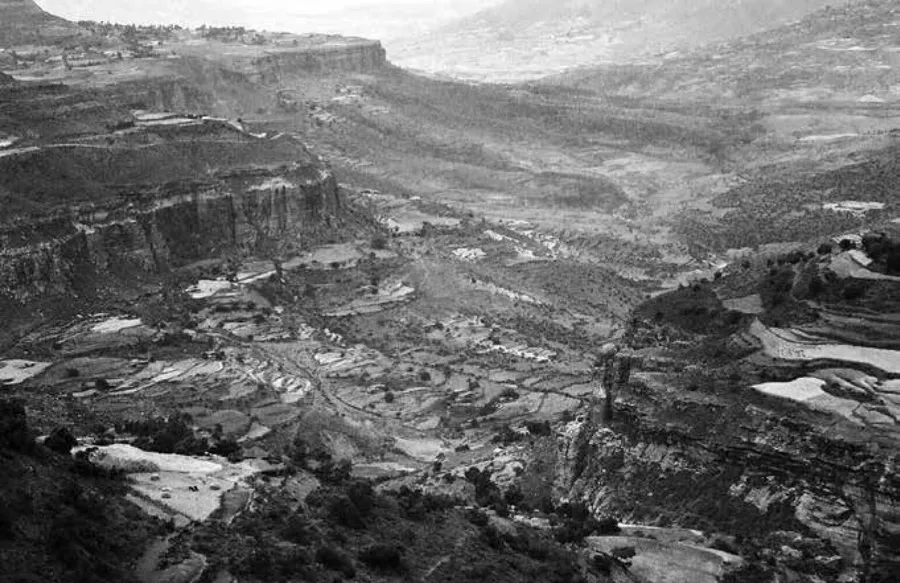

FIGURE 1.1. Mountainous terrain between Axum and Lalibela in Ethiopia (photograph by Johann Wassermann, 1994).

Terrain and topography impact patterns of human settlement and mobility. Clearly, the particular ruggedness of Ethiopia’s terrain has had, over time, a distinct bearing not only on human settlement and mobility but also on security and the economy. The more rugged the terrain, the greater the challenges for transportation and trade. Over the centuries, humans have used ruggedness and altitude to defend their homes and their livelihoods. Fortresses and fastnesses built at higher altitudes allowed for visual and strategic advantage in times of hostility. Accordingly, the Oromo commonly used the terrain to secure their settlements and strongholds in the mountainous regions of Oromoland against marauders and slave raiders. The mountains and the rocky terrain served as a natural fortress.

In Ethiopia, the rugged topography not only provided a modicum of protection against the predations of slave raiders but also presented traders with the problem of postcapture transportation. The external Ethiopian slave trade, which supplied the markets of Arabia and India, was predicated on the successful transportation of slaves from inland regions to established entrepôts on the Red Sea coast. Negotiation of the towering mountains, craggy outcrops, and steep escarpments of the Ethiopian centroid was only possible via treacherous, rocky pathways.

Ethiopian Population and Demographics

Polyethnic present-day Ethiopia comprises as many as eighty different population groups, speaking some eighty-four languages and divided across its nine ethnic regions in a system of ethnic federalism. That Ethiopia’s nine regions are ethnically defined has enabled critics of the system to draw comparisons with the racially driven Bantustans and the general spatial engineering of South Africa’s pre-1994 apartheid regime. The Ethiopian system of ethnic federalism has, in practice, proved one of ethnic dominance, and, as in apartheid South Africa, the ruling group makes up a tiny minority. In 2016, the ruling Tigrayans constituted a mere 6 percent of the total population of 102,374,000. By contrast, the Oromo people amounted to approximately 40 percent and the Amhara roughly 27 percent of the total population.2 Historically, the Oromo have consistently constituted the numerically dominant proportion of the population since incorporation into Abyssinia (old Ethiopia) by Emperor Menelik II in the late nineteenth century. However, as in previous centuries, the Oromo today remain a political minority occupying the administrative region of Oromia.

In earlier writings about the peoples of Ethiopia and in earlier accounts of the Oromo—including in the narratives of the freed Oromo slave children at Lovedale Institution—writers commonly used the term “Galla” to describe the Oromo people. However, in Amharic, the language of the politically and economically dominant Amhara people of Ethiopia, the word Galla means “uncultured” or “immigrants.” The term has long been considered pejorative by the Oromo people, and the use of the old ethnonym, now considered both obsolete and offensive, was declared illegal in 1974.3

In this work, the term “Oromo” is used to describe the largest Cushitic-speaking people of Ethiopia. Although they occupied, in the late nineteenth century, a plurality of principalities, the Oromo people were, as now, united in language, religion, and political culture, most notably the democratic administrative system of gadaa and a collective Oromo identity. While occupying different principalities, each under the leadership of a local king or chief, the Oromo shared what Mekuria Bulcha refers to as the “myth of common descent.”4 In the late nineteenth century, although they shared a common language, they did not, at that time, share a formally defined and named Oromo territory. Despite this, the Oromo principalities hung together across contiguous territory to the south and southwest of Abyssinia in what was then referred to collectively by cartographers like John Bartholomew as “Galla Land” and more recently as “Oromoland.” It was these territories that Sahlé Mariam, king of Shewa (later Menelik II),5 expropriated—and effectively colonized—in the late nineteenth century, absorbing them into his vision for a new, united Ethiopia.6 The unity of Oromo ethnonationalism would finally be recognized in 1991 with the establishment of their own “state-space” in the modern administrative region of Oromia.7 But of course the granting of a state-space within a supposedly unified country neither ensures nor implies self-determination.

Writing in 1885, Rawson W. Rawson, a renowned British nineteenth-century public figure, geographer, and statistician, cites figures given by the celebrated French geographer Jacques Élisée Reclus in an article on European interests in the Red Sea hinterland.8

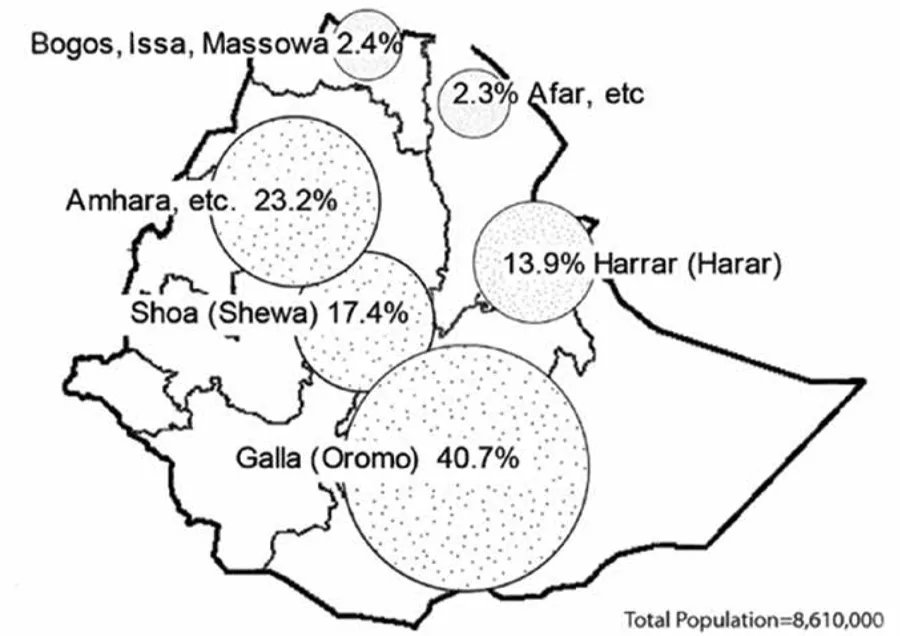

Map 1.2 uses proportional circles to represent Reclus’s relative land and population figures for the different groups in the region roughly covering the area of modern Ethiopia.9

MAP 1.2. Reclus’s population figures overlaid on a modern outline map of Ethiopia (source: generated from Reclus’s data by Sandra Rowoldt Shell).

According to Reclus’s figures, the Oromo represented 41 percent of the total population. The map demonstrates this numerical dominance. Rawson adds a caveat regarding the accuracy of these figures, saying, “They can, of course, only be approximate.”10 Reclus’s figures nonetheless provide an acceptable estimated base of core population data for the region and era in which to embed the Oromo children’s narratives.

Language

Ethiopia’s rulers—and many non-Oromo scholars—often insist that the Oromo people are united only by the Oromo language (Afaan Oromoo). Oromo is an East Cushitic tongue of the Afro-Asiatic language family written in either the ancient Geez script or a modified Latin alphabet named Qubee. While more people (33.8 percent) speak Oromo than any other single language in Ethiopia, the language is also spoken in both northern and eastern Kenya, in Somalia, and in Sudan. It has also been carried farther across Africa by thousands of Oromo people who have fled oppression in Ethiopia in the twenty-first century, seeking asylum or refuge in other countries from Egypt and Libya to South Africa. Across the continent, as the fourth-largest language after the Arabic languages Swahili, and Hausa, Afaan Oromoo is spoken by an estimated fifty million people.11 However, use of the language was significantly repressed from the late nineteenth century until the revolution of 1974. There were few publications by or about the Oromo in their language, and those that did exist were written in the Geez alphabet. In 1956, an Oromo scholar and poet named Sheikh Bakri Sapalo developed a script specifically for Afaan Oromoo, probably designed to conceal the existence of Oromo publications from the Ethiopian authorities. After 1991, the Qubee alphabet was formally adopted. Despite all these politically inspired linguistic hurdles, language is a bonding factor for the Oromo people. However, those who challenge the unity of the Oromo would aver that in every way other than language, they have been—and remain—a disparate people, divided by religion, by interclan squabbling, and by their ready acculturation into the groups among whom they settle.

Religion

While a student at Lovedale, Gutama Tarafo, one of the freed Oromo slave children, wrote a descriptive essay titled “My Essay Is upon Gallaland” (see appendix D in this book), which details an array of features including topography, diet, culture, climate, and religion. Gutama wrote: “The Gallas are heathens in religion. They worship a big tree, and in the mountains. They obey just as the king tells them, and the rule is if a person breaks the king’s commandment, he is taken to the market and punished, by being beaten, or sold as a slave.”

This is the only comment in Gutama’s essay on the religious practices of the Oromo people. Oromo traditional religion is essentially monotheistic, centering on Waaqa, acknowledged as a “Sky God,” a Supreme Being responsible for the creation of the universe. Attached to Waaqa is what Ioan Lewis referred to as a “vague ...