![]()

part I

fall

![]()

chapter 1

the treasure map

The Map Maker: Andreas Schleicher in Paris.

Andreas Schleicher sat down quietly toward the back of the room, trying not to attract attention. He did this sometimes; wandering into classes he had no intention of taking. It was the mid-1980s and, officially speaking, he was studying physics at the University of Hamburg, one of Germany’s most elite universities. In his free time, however, he drifted into lectures the way other people watched television.

This class was taught by Thomas Neville Postlethwaite, who called himself an “educational scientist.” Schleicher found the title curious. His father was an education professor at the university and had always talked about education as a kind of mystical art, like yoga. “You cannot measure what counts in education—the human qualities,” his father liked to say. From what Schleicher could tell, there was nothing scientific about education, which was why he preferred physics.

But this British fellow whose last name Schleicher could not pronounce seemed to think otherwise. Postlethwaite was part of a new, obscure group of researchers who were trying to analyze a soft subject in a hard way, much like a physicist might study education if he could.

Schleicher listened carefully to the debate about statistics and sampling, his pale blue eyes focused and intense. He knew that his father would not approve. But, in his mind, he started imagining what might happen if one really could compare what kids knew around the world, while controlling for the effect of things like race or poverty. He found himself raising his hand and joining the discussion.

In his experience, German schools had not been as exceptional as German educators seemed to think. As a boy, he’d felt bored much of the time and earned mediocre grades. But, as a teenager, several teachers had encouraged his fascination with science and numbers, and his grades had improved. In high school, he’d won a national science prize, which meant he was more or less guaranteed a well-paying job in the private sector after college. And, until he stepped into Postlethwaite’s lecture, that was exactly what he’d planned to do.

At the end of class, the professor asked Schleicher to stay behind. He could tell that there was something different about this rail-thin young man who spoke in in a voice just above a whisper.

“Would you like to help me with this research?”

Schleicher stared back at him, startled. “I know nothing about education.”

“Oh, that doesn’t matter,” Postlethwaite said, smiling.

After that, the two men began to collaborate, eventually creating the first international reading test. It was a primitive test, which was largely ignored by members of the education establishment, including Schleicher’s father. But the young physicist believed in the data, and he would follow it wherever it took him.

the geography of smart

In the spring of 2000, a third of a million teenagers in forty-three countries sat down for two hours and took a test unlike any they had ever seen. This strange new test was called PISA, which stood for the Program for International Student Assessment. Instead of a typical test question, which might ask which combination of coins you needed to buy something, PISA asked you to design your own coins, right there in the test booklet.

PISA was developed by a kind of think tank for the developed world, called the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and the scientist at the center of the experiment was Andreas Schleicher. It had been over a decade since Schleicher had wandered into Postlethwaite’s class. He’d worked on many more tests since then, usually in obscurity. The experience had convinced him that the world needed an even smarter test, one that could measure the kind of advanced thinking and communication skills that people needed to thrive in the modern world.

Other international tests had come before PISA, each with its own forgettable acronym, but they tended to assess what kids had memorized, or what their teachers had drilled into their heads in the classroom. Those tests usually quantified students’ preparedness for more schooling, not their preparedness for life. None measured teenagers’ ability to think critically and solve new problems in math, reading, and science. The promise of PISA was that it would reveal which countries were teaching kids to think for themselves.

By December 4, 2001, the results were ready. The OECD called a press conference at the Château de la Muette, the grand Rothschild mansion that served as its headquarters in Paris. Standing before a small group of reporters, Schleicher and his team tried to explain the nuances of PISA.

“We were not looking for answers to equations or to multiple choice questions,” he said. “We were looking for the ability to think creatively.”

The reporters stirred, restless for a ranking. Eventually he gave them what they wanted. The number-one country in the world was . . . Finland. There was a pause. Schleicher was himself a bit puzzled by this outcome, but he didn’t let it show. “In Finland, everyone does well,” he said, “and social background has little impact.”

Finland? Perhaps there had been some kind of mistake, whispered education experts, including the ones who lived in Finland.

Participating countries held their own press conferences to detail the results, and the Finnish announcement took place fifteen hundred miles away, in Helsinki. The education minister strode into the room, expecting to issue a generic statement to the same clutch of Finnish journalists she always encountered, and was astonished to find the room packed with photographers and reporters from all over the world. She stammered her way through the statement and retreated to her office.

Afterward, outside the Ministry of Education, foreign TV crews interviewed bewildered education officials in below-freezing December temperatures, their jackets flapping in the sea breezes off the Gulf of Finland. They had spent their careers looking to others—the Americans or the Germans—for advice on education. No one had ever looked back at them.

The Germans, meanwhile, were devastated. The chair of the education committee in the Bundestag called the results “a tragedy for German education.” The Germans had believed their system among the best in the world, but their kids had performed below average for the developed world in reading, math, and science—even worse than the Americans (the Americans!)

“Are German Students Stupid?” wondered Der Spiegel on its cover. “Dummkopf!” declared the Economist. Educators from every country, including Germany, had helped Schleicher and his colleagues write the test questions, so they couldn’t dismiss the results outright. Instead, some commentators blamed the teachers; others blamed video games. PISA entered the German vernacular, even inspiring a prime-time TV quiz program, The PISA Show. Education experts began making regular pilgrimages to Finland in search of redemption. Even Schleicher’s father came around, reading through the results and debating them with his son.

Across the ocean, the United States rang in somewhere above Greece and below Canada, a middling performance that would be repeated in every subsequent round. U.S. teenagers did better in reading, but that was only mildly comforting, since math skills tended to better predict future earnings.

Even in reading, a gulf of more than ninety points separated America’s most-advantaged kids from their least-advantaged peers. By comparison, only thirty-three points separated Korea’s most-privileged and least-privileged students, and almost all of them scored higher than their American counterparts.

U.S. Education Secretary Rod Paige lamented the results. “Average is not good enough for American kids,” he said. He vowed (wrongly, as it would turn out) that No Child Left Behind, President George W. Bush’s new accountability-based reform law, would improve America’s standing.

Other Americans defended their system, blaming the diversity of their students for lackluster results. In his meticulous way, Schleicher responded with data: Immigrants could not be blamed for America’s poor showing. The country would have had the same ranking if their scores were ignored. In fact, worldwide, the share of immigrant children explained only 3 percent of the variance between countries.

A student’s race and family income mattered, but how much such things mattered varied wildly from country to country. Rich parents did not always presage high scores, and poor parents did not always presage low scores. American kids at private school tended to perform better, but not any better than similarly privileged kids who went to public school. Private school did not, statistically speaking, add much value.

In most countries, attending some kind of early childhood program (i.e., preschool or prekindergarten) led to real and lasting benefits. On average, kids who did so for more than a year scored much higher in math by age fifteen (more than a year ahead of other students). But in the United States, kids’ economic backgrounds overwhelmed this advantage. The quality of the early childhood program seemed to matter more than the quantity.

In essence, PISA revealed what should have been obvious but was not: that spending on education did not make kids smarter. Everything—everything—depended on what teachers, parents, and students did with those investments. As in all other large organizations, from GE to the Marines, excellence depended on execution, the hardest thing to get right.

Kids around the world took the PISA again in 2003, 2006, 2009, and 2012. More countries had signed on, so, by 2012, the test booklet came in more than forty different languages. Each time, the results chipped away at the stereotypes: Not all the smart kids lived in Asia, for one thing. For another, U.S. kids did not have a monopoly on creativity. PISA required creativity, and many other countries delivered.

Money did not lead to more learning, either. Taxpayers in the smartest countries in the world spent dramatically less per pupil on education than taxpayers did in the United States. Parental involvement was complex, too. In the education superpowers, parents were not necessarily more involved in their children’s education, just differently involved. And, most encouragingly, the smart kids had not always been so smart.

Historical test results showed that Finnish kids were not born smart; they had gotten that way fairly recently. Change, it turned out, could come within a single generation.

As new rounds of data spooled out of the OECD, Schleicher became a celebrity wonk. He testified before Congress and advised prime ministers. “Nobody understands the global issues better than he does,” said U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan. “And he tells me the truth—what I need to hear, not what I want to hear.” U.K. Education Secretary Michael Gove called him “the most important man in English education,” never mind that Schleicher was German and lived in France.

On every continent, PISA attracted critics. Some said that the test was culturally biased, or that too much was lost in translation. Others said the U.S. sample size of 5,233 students in 165 schools was too small or skewed in one direction or another. Many said that Schleicher and his colleagues should just collect test scores and stop speculating about what might be leading to high or low scores.

For the most part, Schleicher deflected his critics. PISA was not perfect, he conceded, but it was better than any other option, and it got better each year. Like a Bible salesman, he carried his PowerPoint slides from country to country, mesmerizing audiences with animated scatter plots of PISA scores over time and across oceans. His last slide read, in a continuously scrolling ticker, “Without data, you are just another person with an opinion . . . Without data, you are just another person with an opinion . . .”

test pilot

I met Schleicher for the first time in April 2010 in Washington, D.C., just after the cherry trees had blossomed on the National Mall. We spoke in the lobby of an office building next to the U.S. Capitol, during his only break in a whirlwind day of meetings. By then, Schleicher had white hair and a brown Alex Trebek mustache. He was pleasant but focused, and we got right down to business.

I told him I was impressed by PISA, but skeptical. By the time of my quest, the United States had wasted more time and treasure on testing than any other country. We had huge data sets from which we had learned precious little. Was PISA really different from the bubble tests our kids had to zombie walk through each spring?

Without bothering to sit down, he took each of my questions in turn, quietly rattling off statistics and caveats, like C-3PO with a slight German accent.

“PISA is not a traditional school test,” he said. “It’s actually challenging, because you have to think.”

No test can measure everything, I countered.

Schleicher nodded. “PISA is not measuring every success that counts for your life. I think that’s true.”

I felt vindicated. Even Schleicher had admitted that data had its limitations. But he went on, and I realized I’d misunderstood.

“I do think PISA needs to evolve and capture a broader range of metrics. There is a lot of work going on to assess collaborative problem-solving skills, for example. We are working on that.”

I got the sense that there was almost nothing, in his mind, that PISA could not measure. If not now, then, one day. Already, he insisted, PISA was radically different from any other test I’d ever taken.

We shook hands, and he headed back inside for his next meeting. As I left, I thought about what he had said. Schleicher, of all people, was a man to be taken literally. If PISA was really different from any test I’d ever taken, there was only one way to know if he was right.

my PISA score

I got there early, probably the only person in history excited to take a standardized test. The researchers who administered PISA in the United States had an office on K Street in downtown D.C., near the White House, wedged between the law firms and lobbyists.

In the elevator, it occurred to me that I hadn’t actually taken a test in fifteen years. This could be embarrassing. I gave myself a quick pop quiz. What was the quadratic formula? What was the value of pi? Nothing came to mind. The elevator doors opened.

A nice young woman who had been ordered to babysit me showed me to an office. She laid out a pencil, a calculator, and a test booklet on a table. She read the official directions aloud, explaining that the PISA was designed to find out “what you’ve been learning and what school is like for you.”

For the next two hours, I answered sixty-one questions about math, reading, and science. Since certain questions could reappear in later versions of the test, the PISA people made me promise not to reveal the exact questions. I can, however, share similar examples from past PISA tests and other sample questions that PISA has agreed to make public. Like this math question:

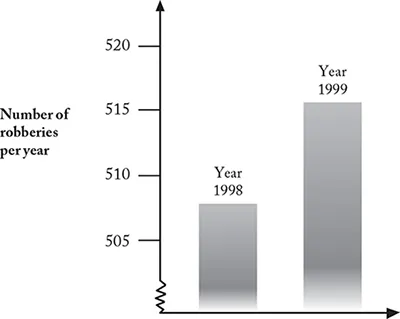

A TV reporter showed this graph and said: “The graph shows that there is a huge increase in the number of robberies from 1998 to 1999.”

Do you consider the reporter’s statement to be a reasonable interpretation of the graph? Give an explanation to support your answer.

Several questions like this one aske...