eBook - ePub

Comparing Democracies

Elections and Voting in a Changing World

Lawrence LeDuc, Richard G Niemi, Pippa Norris

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Comparing Democracies

Elections and Voting in a Changing World

Lawrence LeDuc, Richard G Niemi, Pippa Norris

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

This book provides you with a theoretical and comparative understanding of the major topics related to elections and voting behaviour. It explores important work taking place on new areas, whilst at the same time covering the key themes that you'll encounter throughout your studies. Edited by three leading figures in the field, the new edition brings together an impressive range of contributors and draws on a range of cases and examples from across the world. It now includes:

- New chapters on authoritarian elections and regime change, and electoral integrity

- A chapter dedicated to voting behaviour

- Increased emphasis on issues relating to the economy.

Comparing Democracies, Fourth Edition will remain a must-read for students and lecturers of elections and voting behaviour, comparative politics, parties, and democracy.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Comparing Democracies est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Comparing Democracies par Lawrence LeDuc, Richard G Niemi, Pippa Norris en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Política y relaciones internacionales et Campañas políticas y elecciones. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

1 Introduction: Democracy and Autocracy

In this, the fourth edition of Comparing Democracies, we explore the ever-changing world of electoral democracy. The first edition, published in 1996, compared the electoral rules and practices of the “major democracies” and covered topics such as electoral systems, political parties, participation, and the media, that were prominent in the study of voting and elections at the time. The “third wave” of democratization popularized by Huntington (1991) was still a relatively new phenomenon. By 2002, when the second edition of the book appeared, “democratization” had become a more prominent theme in electoral research and the coverage of countries expanded to include more countries in Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Africa. While the universe of electoral politics continued to expand into the twenty-first century, recognition was already beginning to appear that democratization was not a seamless process and that progressive “transitions” from authoritarianism to democracy were neither inevitable nor irreversible. In the more established democracies, concerns were revived about the rise and persistence of a “democratic deficit” amid a growing recognition that the deficiencies of democratic politics were not confined to environments where democratic institutions and practices were not well entrenched. In the third edition of the book, published in 2010, attention had shifted to “sustaining” as well as “building” democracy. Our ability to classify the growing number of polities conducting elections had also become more problematic, as categorizations of countries as “free,” “semi-free,” or “not free” (Freedom House) or as “liberal” or “illiberal” (Dahl 1989) increasingly failed to capture adequately many of the realities of electoral practice in a growing number of widely different political environments.

The goal of this series has been to reflect both the changing world of elections and changes in scholarship. To a considerable extent, one reflects the other. Thus, this new edition of Comparing Democracies contains several entirely new topics as well as rethinking approaches to some of the more traditional topics of electoral research. It also reconsiders ways in which we measure and categorize democracy, and how attention to the context in which elections take place and the manner in which they are conducted contributes to our understanding of the many nuances of democratic politics (LeDuc and Niemi, Chapter 8; Norris, Chapter 9; Gandhi, Chapter 10). As has been the case with the previous volumes in the series, the emphasis of Comparing Democracies 4 reflects the many developments that have taken place in both the practice of electoral democracy and in the thinking and research of those who study it.

Measuring Democratization

Attempts by social scientists to measure a country's level of democracy or to categorize regimes according to their type of government have always been the subject of some contention. Minimalist measures utilizing one or two key dimensions, such as the competitiveness of elections or the exercise of civil rights, are valued for their simplicity and consistency across time and between systems. One of the older such measures, developed in the 1970s by Raymond Gastil, has long been used by Freedom House to rate all of the countries of the world on two seven-point scales measuring, respectively, political rights and civil liberties (Gastil 1978). As is often the case with comparative measures that have been used over a long period, the Freedom House indices are useful for tracking changes over time, as well as for drawing comparisons among countries. The most recent Freedom House ratings of countries on these measures may be found on the Freedom House website (www.freedomhouse.com). Similarly among older measures, Polity IV (www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm), originally developed by Ted Robert Gurr (1974), also differentiates procedural variations in democracy and autocracy among countries. Other newer indices include or weight differently core attributes, allow more disaggregation, or attempt to measure characteristics associated specifically with the conduct of elections (Munck 2009). Some of these may be found in the Quality of Governance Dataset, which is available for download at the University of Gothenberg (www.qog.pol.gu.se). Depending on which measures are employed, a regime at any given time may appear to be classified as more or less democratic or autocratic. Fortunately, however, there is a very substantial degree of correlation between the various measures that are commonly employed by scholars to measure democracy (Norris 2008). It can also be shown that, while a country may be rated differently on certain specific attributes such as the inclusiveness of elections, the rule of law, or the protection of civil liberties, these align strongly on a single hierarchical dimension that may be thought of as “democratic accountability” (M⊘eller and Skaaning 2010).

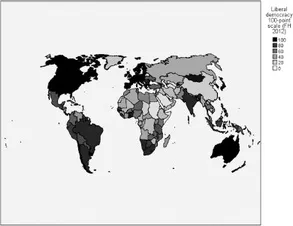

Given this convergence, it is not so difficult to distinguish, at least conceptually, the most clear-cut democracies from autocracies. Figure 1.1 provides a map of all independent nation states based on a 100-point standardized scale constructed from Freedom House's combined rating of political rights and civil liberties, ranging from most autocratic (low) to most democratic (high). There is no perfect democracy. And, increasingly, there are fewer absolute autocracies in which some form of electoral politics cannot be found. While this conceptualization does not resolve the problem of measurement, it does encourage us to think of elections on a global scale.

Figure 1.1 Map of Liberal Democracy, 2012

Source: Based on Freedom House ratings (www.freedomhouse.org)

Categorizing Democratic and Autocratic Regimes

Earlier editions of this book would not have discussed autocracies at all, other than for the purpose of identifying those countries without multiparty elections and excluding them from further consideration. However, we now live in a world where all but a handful of countries hold elections of some kind. While the integrity of such elections varies widely, there is now a considerable body of scholarship that examines the implications of elections taking place in authoritarian regimes (Gandhi and Lust-Okar 2009; Levitsky and Way 2010; Lindberg 2009). In Chapter 10 of this book, Jennifer Gandhi examines the meaning and significance of elections held by authoritarian governments that would simply have been excluded from consideration in many earlier studies. Pippa Norris (Chapter 9) also addresses a new topic (Electoral Integrity) that examines the conduct and management of elections in both authoritarian and democratic regimes.

While we do not attempt to typologize democracies and autocracies here, as was done in previous editions of this book, many cases are readily classifiable based on continuous measures such as the Freedom House or Polity IV scales discussed above. Countries such as Belarus, Sudan, and North Korea continue to receive Freedom House's lowest political rights score (7) and would be considered autocracies by any objective standard applied. Elections in these countries, when they take place, would never be thought of as free and fair contests. Likewise, it is easy to classify countries with strong democratic institutions and long-established democratic practices, such as Canada, Sweden, or Japan, as “liberal democracies” based on their routinely receiving the highest political rights score (1) assigned by Freedom House or other similar international bodies. The results of elections in these countries, despite occasional controversies or allegations of wrong-doing in specific elections, are readily accepted as fully legitimate expressions of the public will. But there are many gradations of ratings of democracy and autocracy, even when applying very limited measures such as the Freedom House scales. South Africa's rating of 2 on the political and civil rights measures suggests that it is not as fully democratic as New Zealand or Germany. This is perhaps because of the firm grip that the ruling African National Congress has held on power since the first multiracial election following the end of Apartheid in 1994. In its 2013 report on South Africa, Freedom House also mentions ongoing issues such as press freedom, discrimination against women in some sectors of society, and corruption (www.freedomhouse.org). More precarious is the present regime in Russia, which received a rating of 6 on political rights from Freedom House in 2012 – substantially lower than the rating it received from the same agency (4) in 2000 when President Putin was first elected. In its 2013 report, Freedom House characterized the 2012 election that returned Putin to the presidency as “tightly controlled” and notes serious restrictions on press freedom and the lack of judicial independence as ongoing problems in that country.

Some problems of electoral integrity can also arise even in seemingly well-functioning democracies (Denk and Silander 2011). A “dirty tricks” campaign scandal marred Canada's reputation for conducting clean elections in 2011, and sporadic abuses of executive authority are a continuing source of criticism of the performance and functioning of Canadian democracy (Lenard and Simeon 2012). In the United States, controversies over alleged electoral fraud and voter repression have become far more polarized and intense ever since the problems in Florida during the 2000 presidential election. Conversely, countries that might be classed as more autocratic also conduct multiparty elections, and those elections may be meaningful in terms of providing opportunities for public expression of interests, means of organization, or legislative representation, even if they do not directly threaten to topple the governing authorities. The 2008 presidential election in Zimbabwe, despite widespread allegations of fraud and intimidation, produced a power-sharing agreement. Scholars continue to advocate binary classifications of regimes types, using a few simple decision-rules, on the grounds of parsimony and rigor (Alvarez et al. 1996; Boix et al. 2013; Cheibub et al. 2010). Given the number of countries that now conduct elections, however, and the wide variation in the political circumstances in which elections can take place, simple dichotomous classifications of “democracy” and “autocracy” no longer seem adequate, even though the concepts themselves continue to represent polar opposites. More complex and uncertain are cases that fall close to the mid-point of a democracy/autocracy continuum, or that might be classified differently by applying alternative criteria. Malaysia, for example, receives a rating of 4 on both the political rights and civil liberties measures compiled by Freedom House, situated exactly at the mid-point of both scales. Making a binary classification based on these data would be difficult. In its 2013 report, Freedom House states that the ruling party “used a combination of economic rewards, reformist rhetoric, and continued repression of opposition voices” over the year leading up to the most recent election and that “the government retains considerable powers to curb civil liberties and control the media” (www.freedomhouse.org). Yet in the election itself, held in May 2013, the main opposition party took 47% of the popular vote and 89 of the 222 parliamentary seats. Turnout was a robust 85%. While Malaysia retains a number of authoritarian practices in its politics, elections in recent years have been more closely contested. Whether we choose to classify Malaysia as an autocracy or a democracy, it is clear that its elections have meaning.

The Changing World of Electoral Democracy

The changes that have taken place globally in the practice of democratic politics are in many ways more revealing than comparisons between countries. The past four decades have seen considerable change in the classifications of countries as democracies or autocracies, reflecting both specific changes within certain countries as well as broader global trends. Figure 1.2 displays the merged Freedom House political rights and civil liberties scores for 1975 in a scatterplot against the most recent scores (2012).1 The pattern identifies clearly the long-standing autocracies (lower-left quadrant) such as Cuba, Laos, or Syria, as well as countries that exhibited modest change in the ratings over that long period but remained generally consistent in their classification (e.g., Nigeria, Kazakhstan, Jordan). Likewise, the long-term stable democracies, such as Italy or Japan, cluster near the regression line in the upper-right quadrant, while others, such as Israel or India, display somewhat more variation in scores but fall clearly within the same cluster. The wave of democratization of the latter part of the twentieth century stands out, however, with many of the countries of Eastern Europe, Latin America, or Africa falling within the upper-left quadrant – formerly autocracies, now democracies. A shorter-term picture, as might be expected, displays much less change (Figure 1.3). However, changes, when they do occur, can be dramatic and are not necessarily in the direction of transitions toward democracy. A military coup in Thailand in 2006 deposed a democratically elected government. While democracy has since been restored, Thailand's 2012 rating on the political rights and civil liberties scores is a neutral 4 – lower than in the period before the coup. In its 2013 report, Freedom House noted that “Prime Min...