![]()

PART I

THE CENTRE OF

ALL THE WORLD

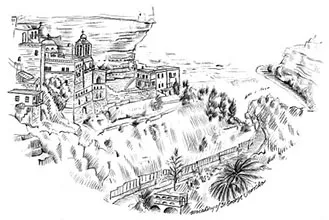

I am surrounded by the cultures and memories of the city that are lived everyday throughout their residents' lifestyle. Jerusalem, a magnificent city in all her grandeur, impresses me with every sight I see.

(Ibn Battuta)

Leaving Jerusalem

Someday – when I set off on another long journey perhaps – I will begin my travelling in the afternoon, after a long sleep and a lingering breakfast. I would also like to embark without a headache induced by too many ‘farewell’ beers the night before. Finally – and it doesn't seem too much to ask – I'd like that first day to be an easy one with little to challenge me physically or otherwise so that I might ease into the quest gently. Unfortunately, I have been promising myself these luxuries for years, and they have yet to come to pass. There appears to be an unwritten rule book for expeditions, and feeling thoroughly miserable and exhausted at the outset seems to be absolutely imperative.

An hour before the first rising sun of December breached the barren shale hills beyond the walls of my room in the Jerusalem Hotel, I wrestled myself awake, shrugged an unfamiliar weight onto my shoulders and stepped outside to take the first of 2 million-odd steps. With me were four companions: Dave, a friend from London and a permanent fixture on the journey, and Matt, Hannah and Laurence who, as expats in Jerusalem, would act as auxiliary guides to get us out of the city.

Bleary-eyed, I stumbled past the dawn street vendors with their circular bread and bags of za'atar, across a main road where teenage Israeli army conscripts sagged under the weight of their automatic weapons, and finally on to the archway of the Damascus Gate, one of eight remaining openings into the Old City of Jerusalem, the holiest square mile of land on the planet.

Behind the towering stone fortifications of the gateway, the various fractured districts of Jerusalem sprawled out across a plateau on the Judaean Mountains, wedged in between the Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. This was once considered to be the centre of the world8 – Benjamin Disraeli famously said that ‘the view of Jerusalem is the history of the world’– and it tells a story of villains and heroes, heresy and faith, mercy and bloodshed (especially bloodshed). The city has twice been reduced to nothing, has been besieged on over 20 occasions, and captured enough times to make one wonder how it ever remained in existence to this day and age. Above all, the chronicles of Jerusalem are a tale of the vicissitudes and weaknesses of mankind – the building of great empires, their subsequent violent destruction, and our eternal failure to learn from mistakes of the past. It is a city that despite all of this transcends the physical, becoming a celestial symbol: the beating heart of the Holy Land.

Jerusalem's beginnings were inauspicious. The first residents were farmers who, some 6,000 years ago, made a home around the Gihon Spring area, a few miles from the medieval city centre that still survives today. Since then, control of the coveted city has often been wrested but rarely retained, slipping through the hands of each victor in turn like sand through an hourglass. Material remnants of much of Jerusalem's chequered past are long gone, yet in places there is a palpable presence of that which has come before. Nowhere is this more apparent than within the walls of the Old City itself, where glimpses of powers past peek out at those who know where to look, showing how each stratum of history was created from the ruins of the last, in turn becoming a building block for the next and, ultimately, leading to the contemporary cauldron of the modern city.

Below the Ottoman architecture of the Damascus Gate itself is a small and unpretentious triple-arched gateway that has survived since the time of the Emperor Hadrian, nearly 2,000 years ago.9 The Roman occupation also endures on the market street, the Cardo, which still runs north to south, bisecting the Old City. Much of the rest of the street plan dates from Byzantine times. How do we know? Experts tell us, but even to an untrained eye it is easy to see where 1,000-year-old stone walls have been added to by 200-year-old brickwork, and finished off with a twenty-first-century piece of corrugated iron to act as a shelter for the modern-day bazaar.

Each of the gateways through the great city walls was originally built at an angle, to slow down enemies on horseback. Now those alcoves are home to market stalls and to stony-faced Israeli soldiers. Once through the Damascus Gate our party turned abruptly, and began to wander slowly along narrow streets where hundreds of years of human traffic had worn the cobbles smooth, like rocks sculpted by the sea.

The Old City has traditionally been split into four uneven quarters, and we passed first through the largest, the Muslim Quarter, just as it began to wake. In a few hours the streets would be an ocean of people – locals and foreigners alike – twisting and swirling and colliding in the winding labyrinth of alleyways. The sides of each passage would fill with produce and merchandise – from cabbages to kebabs, and from Christian icons and Arabic carpets to candles, key rings and snow globes. Religious division and sectarianism often take a back seat to business in tourist hotspots like this, and even in the early hours bearded Muslim shopkeepers were offering ‘Free Palestine’ T-shirts alongside those emblazoned with ‘Stand up for Israel’. ‘Just Jew It’ seemed a bestseller, with a picture of a soldier surrounded by the Star of David.

Each step further, and each minute that passed as the city stirred, brought more life into the souq. Heavy aromas of fried food and freshly sliced fruit mixed with the scent of a thousand aftershaves, and, floating underneath all else, the smell of the gutters was mercifully subtle. Elderly Arab women in swathes of black material bent double over cardboard boxes packed tight with vegetables – most of which had come straight from bountiful fields in the Jordan Valley – while sleepy-looking young men crouched on haunches in doorways, hair plastered tight to their heads with gel, fitted polo shirts stretched across their slight frames. In a room above us someone babbled loudly into a mobile phone on loudspeaker. Technology aside, much of this scene felt like it could have been playing out unchanged for hundreds of years.

We turned right on the Via Dolorosa, following the route that Jesus had walked, under the weight of his own cross, on his way to be crucified. An invisible barrier had been crossed and we were now in the Christian Quarter, a disorientating but pleasant warren of pathways with a baffling assortment of churches and hospices peeping out from alleyways and looming down from above. The centrepiece here is the magnificent Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the holiest site in Christendom. Unsure of how else to mark arriving at Calvary itself, I sought my own religious experience through the medium of breakfast: fresh simit bread covered in toasted sesame seeds and two warm, steaming falafel.

Towards the end of the third decade of the first century AD,10 a young Galilean Jew called Jesus – having survived the purge of the Roman king Herod in Bethlehem – began travelling around Galilee and Judaea preaching the word of God. His life was not a long one – at least not in earthly terms – but it was certainly productive. The New Testament places his crucifixion as taking place on a hill at Golgotha, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is now built over this original site, also covering the tomb from which Jesus was resurrected. As the Christian sect grew in the centuries after his ascension to heaven, culminating in the Roman emperor Constantine I ending persecution in the fourth century, Jerusalem became the cradle of this new religion – the pivot for an ever-expanding Christian world. The first documented spiritual journey there was made by an unnamed pilgrim from Bordeaux, whose account from AD 333 reads:

On the left hand is the little hill of Golgotha where the Lord was crucified. About a stone's throw from thence is a vault wherein his body was laid, and rose again on the third day. There, at present, by the command of the Emperor Constantine, has been built a basilica; that is to say, a church of wondrous beauty.11

That wondrous beauty is still apparent to all who see the church, and we gazed upon it for a long time from our seat on the cobbles. Fear and loathing are late risers in Jerusalem, and the early morning is perhaps the most tranquil and harmonious time to see the city. A food cart beside us was watched over by a middle-aged Arab in a grey thobe and black-and-white keffiyeh, and, as we munched, two young Jews in casual jeans and loose shirts ambled past, knitted kippot clinging to the backs of their heads. An ultra-Orthodox Haredi marched along a little way behind, his long black beard and curled payot bouncing in rhythm and his long black coat hiding everything but a scuffed pair of pointed dress shoes. Coming the other way, a Greek Orthodox priest in a black tunic with red trim stopped briefly beside us, attracted by the wafting smell of frying chickpeas just as we were. This cast of characters all ignored one another, but not for reasons of fear or discomfort – they were simply on their own missions, and each was unimportant to the other. In Jerusalem, to see mutual disregard is a pleasant departure from witnessing mistrust.

According to the Hebrew Bible, Jerusalem – Yerushalayim in Hebrew – was the site of the first Jewish temple, and since then it has been seen as the spiritual homeland of the Jewish people.12 In Islam, while the city is not mentioned by name in the Qur'an, other sacred texts mark it as the place where the Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven.13 Islam continued to expand rapidly after Muhammad's death in AD 632, soon stretching from Spain in the west to India in the east. Jerusalem – Al Quds in Arabic – was quickly conquered by the armies of the converts, and Muslim rule lasted for nearly 400 years, but in the eleventh century the papally ordained zealots of Europe rode on the Holy Land to claim it back for Christendom. In 1099 the Crusaders arrived in the city, slaughtering Muslims, Jews and all others in their path, thus beginning one of the goriest chapters in the already blood-soaked history of Jerusalem.

As a crossroads of faiths Jerusalem has always had devotees of many diverse religions, but now, placed as it is at the heart of the contemporary Israeli–Palestinian question, it is the most high-profile place where Jews and Muslims quite literally rub shoulders on the same city streets. At its best, Jerusalem can embody the hope that two peoples and two states can exist peaceably side by side. At its worst, it becomes a pressure cooker of hatred and animosity and, at the time of travelling, it was experiencing one of the lowest ebbs of mutual suspicion seen in recent years. Throughout the city, soldiers of the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) patrolled along busy intersections with weapons gripped tightly, and it was not unusual to see Israeli civilians wearing stab-proof vests and carrying handguns on their hips.14 During my time in the city I had seen three separate Palestinian teenagers being pulled aside by soldiers and roughly patted down for anything that might resemble a knife. All were carrying nothing but cigarettes and mobile phones, and looked truly terrified (as did most of the Israeli civilians in vests, and indeed some of the soldiers).

Jewish immigrants had been trickling into Palestine15 since the late 1800s, but it was in the aftermath of World War I that their numbers really began to grow, with refugees from the Balkans, the Soviet Union and the Near East fleeing persecution. World War II, and in particular the atrocities of the Holocaust between 1941 and 1945, saw a further movement of Jews towards the perceived safety of the Holy Land. Slowly however, as the demographics shifted, tensions and mutual resentment began to grow among the Jewish and Arab populations. Violence escalated on the streets between old residents and new, forced into increasingly close proximity, and in the corridors of power things were even worse; the British had secretly promised Palestine to both the Arabs and the Jews. In 1947, with the situation dire and seemingly beyond their power to resolve, the British washed their hands of it. When their Mandate ended in May 1948, the state of Israel declared independence and the inevitable happened: war ensued. To Palestinians, and in much of the Arab world, this is known as the Nakba, or ‘the Catastrophe’.

Ten months of civil war left the land of Palestine and the city of Jerusalem split along physical and ethnic lines. The west of the city belonged to the new Israeli state, and the east was annexed by Jordan. In 1950 Israel declared Jerusalem its capital. In 1967 the ‘Six Day War’ was fought: Israel launched a pre-emptive strike against its regional enemies Jordan, Syria and Egypt, resulting in the seizure of the Golan Heights, the Sinai Peninsula, the West Bank16 and East Jerusalem. Sinai was eventually ceded back to Egypt and in 2005 Israel pulled out of Gaza, but Jerusalem has remained divided, with the eastern area of the city annexed. The Israeli parliament, the Knesset, claims Jerusalem as its ‘eternal and indivisible capital’,17 but the international community refuses to acknowledge the occupation.

For their part, Palestinians see Jerusalem as the capital city for a future state which they hope will one day soon come into being. As it stands, Palestine (as a political entity) is only partially recognised by the international community. The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) emerged shortly before the Six Day War as an umbrella organisation for the various factions that sought to represent those fighting – politically and otherwise – for the Palestinian cause, and it is this national front that has, at the time of writing, been recognised by 136 of the 193 member states of the United Nations. The Palestinian Authority meanwhile – the interim government of the Palestinian territories – has been granted non-member observer status in the UN. What hasn't changed is that 4 million Palestinians living in the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem are still stateless. Tensions between Israelis and Palestinians are today as high as they've ever been, and peace in the region seems farther off than ever before. The city that is the spiritual nucleus for the 3.5 billion followers of the Abrahamic faiths is in danger of self-destructing through religious and ethnic civil war. However, if one thing is clear from the history of Jerusalem it is that nothing lasts forever, and perhaps for once that can be a small source of encouragement.

To reach the southern city walls, we wound our way in and out of the Armenian and Jewish Quarters. Much of the Jewish Quarter has been reconstructed since large areas were destroyed in the Six Day War. The exception was along the Cardo, the main north–south thoroughfare, where a small clump of Roman columns had been excavated and maintained and beside which a busy underground mall sold Judaica to the first tourists of the day. Beyond that to the east, past the mosaics and yeshivas and ornate beauty of domed synagogues, lay the Western Wall compound and, farther still, the Haram ash-Sharif, known to the Jewish people as the Temple Mount.18

The Armenian Quarter is the smallest of the four and is distinct from the Christian area (despite Armenians being Christian). Christianity in Jerusalem is full of sects – a cursory walk through the city reveals Greek Orthodox, Greek Catholic, Roman Catholic, Syriac Catholic, Syriac Orthodox, Maronite, Anglican, Armenian Orthodox and Armenian Catholic. The Armenians are the most fiercely independent and have had a presence in the city since the fourth century. The Quarter is a complex of multiple historical sites that have morphed into a self-sufficient community, and our path to the Jaffa Gate – our exit – was lined with small restaurants that smelt of fried garlic and cumin, and shops with big windows and striped awnings offering traditional Armenian ceramics for sale.

We crossed a busy main highway where oversized American-style cars with Israeli number plates idled by a stop light, then climbed the gentle but unrelenting stone staircase that ascends the hillside leading to the Mount of Olives – one of the highest points in the city and a common location for New Testament happenings.19 A group of about 20 schoolchildren paused on their way to school to examine us; who were these strange creatures who were sweating so profusely at half past six in the morning?

The sun was fighting a losing battle with bulbous grey clouds, but here and there it sliced through in sharp, direct pinpricks of celestial light, illuminating oblivious neighbourhoods of a sleeping city. Not far from where we stood lay the Garden of Gethsemane where Jesus prayed hours before his crucifixion; beyond that was the site of his apparent last footprint on earth – now housed inside a mosque – and beside that thousands of ancient graves on terraces leading back down to the buttressed walls from whence we'd come. The iconic golden dome of the Qubbat Al-Sakhrah, or Dome of the Rock, reflected back a strand of divine sunlight over the Haram ash-Sharif/Temple Mount, connecting heaven and earth, however briefly.

In an academic, historical or religious context, there are many things which can be said to define Jerusalem – these centres of faith and shrines to antiquity are just some of them. To someone on foot, however, and especially someone at the beginning of a long expedition, the main feature of the landscape is much more prosaic. It is a town built on hills. To look out from on high in Jerusalem is to watch an unlikely assortment of white and beige climbing over the hillside; limestone and breezeblocks punctuated by minarets and steeples and the occasional high-rise. It is impossible to travel anywhere in Jerusalem without going up or down, often repeatedly.

Atop the hill I was uncomfortable. Had I been a pilgrim at the end of a lengthy and pious expedition I might have felt differently, but more than ever I was acutely aware that I was just a walker and uneasy about the prospect of so much walking ahead. I wanted to put some miles behind me so that I might begin to enjoy the experience. Perhaps I would return here, insha'al...